Authored by the Archivist at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, Hannah Mandel the paper “Processing Fluxus and Media Art Histories: A Case Study of the John G. Hanhardt Archives at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College” was presented at the 112th College Art Conference in Chicago within the session Activating Fluxus, Expanding Conservation organized by our research team on February 15, 2024. Below we have made the script of her presentation available to everyone who was unable to attend the conference.

In 2013, the Center for Curatorial Studies Archives acquired the archives of John G. Hanhardt. A seminal figure in the history of media art, John Hanhardt was the curator of Film and Video at the Whitney Museum of American Art from 1974-1996, Curator of Film and Video at the Guggenheim Museum from 1996-2006, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Nam June Paik Media Art Center from 2006-2015.

1. Portrait of John Hanhardt at Whitney Museum of American Art, Photograph by Helaine Messer, 1980; 2. John Hanhardt , Passport photos, undated; 3. John Hanhardt and Nam June Paik Whitney Museum of American Art, 1982. Excerpt from the presentation “Processing Fluxus and Media Art Histories: A Case Study of the John G. Hanhardt Archives at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College” by Hannah Mandel delivered at 112th CAA Chicago.

The Hanhardt Archives are a large collection—roughly 125 linear feet of archival storage, or 300 full size archival boxes—as well as a significant portion of oversized material. Because of its scale, and our limited staff at CCS (we employ one archivist, as well as a director of libraries and archives, and solicit part time help from student employees on processing projects), as well as the organizational structure of the papers upon our acquisition—that is, very li le, an almost flat content structure—the processing of the Hanhardt Papers has been ongoing for eleven years.

Over his 50 plus year career, Hanhardt curated hundreds of exhibitions, wrote extensively on the development of video art and media art, and taught and lectured at an extraordinary number of institutions. While Hanhardt is widely associated with his early and continued support and exhibition of Nam June Paik, the curator maintained long term relationships with many artists.

1. Poster for Nam June Paik and Charlotte Moorman performance, Spring Arts Festival, University of Cincinnati, April 1,

1968; 2. Nam June Paik in studio. 20 photograph by Jon Huffman; 3. Installation view, Nam June Paik,”Global Groove

2004″, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY. Excerpt from the presentation “Processing Fluxus and Media Art Histories: A Case Study of the John G. Hanhardt Archives at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College” by Hannah Mandel delivered at 112th CAA Chicago.

Spread throughout this collection is a half-century of collected correspondence, ephemera, multiples and artworks created by a staggering number of artists, documenting both relationships fostered by Hanhardt, as well as what I refer to as “incidental archives,” that is, troves of material documenting artistic practices that, in many cases, were not solicited or reciprocated by Hanhardt. This includes unopened mail, unanswered queries, automated mailings sent by mailing lists that the curator may not have even knowingly subscribed to.

While traditional archival methodology asks us to respect the “original order” of the collection, it was clear to me and my supervisor that these caches had high research value, and therefore we undertook the immense effort of identifying and isolating material directly related to nearly 1000 different artists, and nearly 800 separate art and film venues, including museums, galleries, publications and institutions.

As I mentioned, It has been my ultimate responsibility to create an archival finding aid for the Hanhardt Papers.

An archival finding aid is a document that consists of descriptive, contextual and structural information about an archival resource. Archival finding aids serve as guides to a collection. Archival finding aids follow standards set forth by governing bodies on how to organize and present information in a way that makes the information not only standardized, but interoperable.

Archival finding aids are often the only point of contact between a researcher and an archive prior to an in-person visit, and the challenge of writing a finding aid thus lies in formulating a document that is as descriptive as possible; which highlights the contextual relationships between entities, which may not be legible otherwise.

The creation of an archival finding aid can perhaps be seen as the initial layer of activation in an archive. Though scholars may think (and not without cause) of archives as having an inherent structure, archival processing always imbues some level of subjective interpretation on the part of the processing archivist.

In this way, archivists are responsible for the initial level of activation in an archive, through their inclusions, omissions and contextual bridges built through the parameters of description.

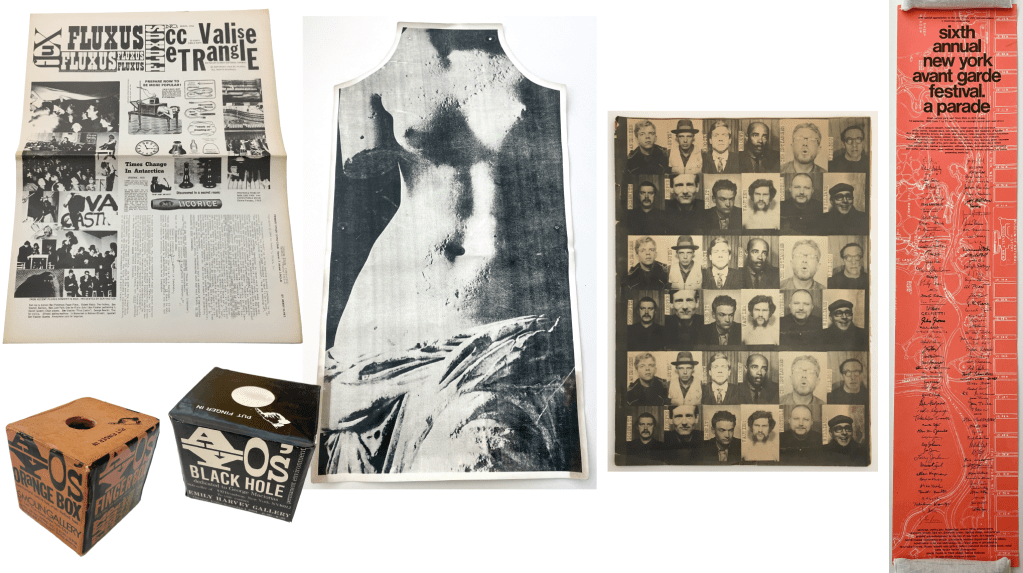

1. Fluxus journal, “CC Valise Etrangle”, headline “Prepare Now to Be More Popular!” March 1964;

2. Ay-O’s Finger box, designed by George Maciunas, addressed to Paul Cummings. Ed. of 50. Unsigned, 1964, and Ay-O’s Finger box, “Black Hole,” 1991. Produced for “Ay-O’s Rainbow Hole” and “Ay-O’s Black Hole” exhibitions at Emily Harvey Gallery, 11/1-12/7/1991; 3. George Maciunas, Venus de Milo apron, Screen printed vinyl with grommet holes, produced by Fluxus Edition, New York, 1973; 4. “Actions/Agit-Pop/ De-Collage/Happen-ing/Events/Antiar-t/Loutrisme/Art Total/ Refluxus” Catalog, Festival der neuen kunst, Aachen, 20 July 1964; 5. Poster, Sixth Annual New York Avant Garde Festival, 14 September 1969. Excerpt from the presentation “Processing Fluxus and Media Art Histories: A Case Study of the John G. Hanhardt Archives at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College” by Hannah Mandel delivered at 112th CAA Chicago.

I’m now going to give some examples of Fluxus material in the Hanhardt Archive in which archivist interventions promoted this initial level of activation.

The Hanhardt Archives are a rich repository of Fluxus material. John Hanhardt is a collector of Fluxus art objects, accumulated through personal relationships with the artists, including a very close, decades long relationship with Nam June Paik and Shigeko Kubota, as well as a close relationship with Ken Friedman, Jonas Mekas, Hans Breder, Yoko Ono, Charlotte Moorman, Jon Hendricks, and the Fluxus collector Jean Brown. Hanhardt also purchased Fluxus objects through his friend Barbara Moore, book dealer of contemporary art and Fluxus publications and ephemera, through her stores Bound & Unbound and its predecessor, Backworks. The archive includes original Fluxus publications and multiples, performance ephemera, media, and documentation of Hanhardt’s involvement in intermedia pedagogies, including at the University of Iowa and Arizona State University.

While Hanhardt did collect original Fluxus material from the 1960s and early 1970s, the bulk of the Fluxus material in the Hanhardt Archives dates from 1974-2001, presenting an early Fluxus historiography—insight into how key figures perceived the legacy of their contributions in the years immediately following the movement’s height, and how scholarship developed around Fluxus. The Fluxus material in the Hanhardt collection is activated by archival description that prioritizes relationships between subjects and events, reflecting the personality, relationships and robust collecting tendencies of Hanhardt himself. In many cases, the processing of the Fluxus material in the Hanhardt Archives exemplifies the need for “descriptive intervention” when writing a finding aid. I am going to describe such examples today.

Though archival best practices generally prioritize the concept of a respect for the preservation of the “original order” of the material— that is, to preserve the context in which the material was delivered to us— in the case of the Hanhardt Archives, the items were, in many cases, including this example, delivered to us in a flat organizational structure, meaning this document was loose among a myriad of other material, not organized by date, and packed randomly and without contextual neighbors. So, it falls on the Archivist to determine how to best create groupings that facilitate the discovery of this material. It is not feasible, in the case of an archive this large, to simply describe material on an item level. Therefore, what standardized groupings can be applied to this type of document?

In the case of this example, which is an undated document containing a call for research material relating to Fluxus from the Henie Onstad Museum in Norway, several artist names are mentioned on the document.

There are robust artist files for several of these artists in the Hanhardt Archives, so it does not make sense to include this document in one selected artist’s folder. The next logical conclusion would be to file this under the venue, “Henie Onstad Museum.” However, we are not truly able to describe each individual item in this archive at an item level, and there is not a significant trove of additional material on Henie Onstad, which would mean the item would be filed under “Venue H,” a category which is necessary due to the sheer amount of material in the archive, but does not provide much contextual information to a researcher using the Finding Aid to access Fluxus material in the Hanhardt Archives.

This level of decision making illustrates the myriad of interventions contributed by the archivist while processing an individual archival item. And, the archive is comprised of hundreds and thousands of items. When viewed in this context, one may understand: A, why the processing of this collection has been ongoing for eleven years, and B, that decision making by the archivist is in fact, highly subjective, based on the archivist’s areas and levels of expertise and deep familiarity with the collection — an activation of the collection prior to that of historians, researchers and other accessors of the collection.

These decisions, as archivist Anna McNally writes in her paper, “All That Stuff! Organising Records of Creative Processes,” in the archivist’s “cataloguing process do not allow for uncertainty or indecision.” Archivist decisions made prior to researcher access influence both the ease of information access and the accessors’ view of the relative importance of a particular item or grouping.

1. Nam June Paik, Whitney Museum temporary staff ID badge, for installation, with photograph, signed by the artist;

2. Nam June Paik. Violin from unknown performance”One for Violin Solo.” n.d. 3. Nam June Palk, “Robot K-456 staged accident” outside the Whitney Museum of American Art. black and white photograph, framed, Photograph, George Hirose, 1982. Excerpt from the presentation “Processing Fluxus and Media Art Histories: A Case Study of the John G. Hanhardt Archives at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College” by Hannah Mandel delivered at 112th CAA Chicago.

I would also like to speak about the general categorization of Nam June Paik material in the Archive. The Paik material is a focal point of the Hanhardt Archives, and dispersed throughout the collection under various series categorizations.

Notably, there is a distinction, or lack thereof, between material generated organically— that is, through the organization by Hanhardt of exhibitions by Paik— including the Whitney Museum exhibition in 1982, and the Guggenheim Museum exhibition, “The Worlds of Nam June Paik,” in 2000, which traveled to the Guggenheim Bilbao and the Samsung Museum in Korea in the years following. Additionally, there are records of dozens of other Nam June Paik exhibitions curated by Hanhardt globally.

Other “organic” troves of Paik material include direct correspondence between Hanhardt and Nam June Paik, and the artist’s studio, not related to a specific exhibition. The inclusion of “secondary” Paik material starts to appear in examining ephemera, some of which was obtained directly from Paik, but much of which was obtained through Hanhardt’s collecting—including, notably, original material purchased thorough Bound & Unbound and Backworks documenting Paik (and Charlotte Moorman’s) activities and exhibitions prior to his relationship with John Hanhardt—in the early 1960s.

Another trove of material is media, of which the collection has over 1500 objects, ranging from film, to VHS and DVD, and more obscure media carrier formats, such as Videodisc VHD. Further complicating the already intellectually, and originally nuanced organization of the Paik material is the inclusion in the Hanhardt archives of material relating to the development of the Nam June Paik Archive Collection at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington DC, which was initiated in 2009. The Hanhardt Archives hold a substantial amount of facsimiles of archival documents included in the Smithsonian Archives.

The question arises, in all these layers of provenance and remove, to determine how to describe this material in a manner that succinctly illustrates its material history as well as subject matter. In many ways it is a distillation of the ultimate paradox of archival description, in that there is always a tension between the description of the item itself, its physical place, versus its intellectual classification.

In talking about processing this archive, I am reminded of the task of untangling a large and unwieldy knot. There is no straightforward path forward, other than slowly and methodically making passes at untangling, until the strands are apparent. At a certain point, we must make the determination that enough passes have been made, and the strands are untangled enough to be legible to scholars. This is with the understanding that things can always be further untangled, and in these cases, I think it is very important to note the impact that our researchers have on archival description.

Archivists make an initial activation of the material through descriptive language and decisions made, but finding aids are living documents, and can always be updated with further contextual information and passes, often brought to us by archive users.

An example of this is the use of original Nam June Paik audiovisual material from the Hanhardt Archive in a documentary film about Paik. Whereas we are not able to digitize all of the media in the Hanhardt collection, because of the constraints of our institution size, the additional input from the researchers as to the context and importance of these archival materials has greatly improved the level of description I am able to assign to these objects. This is an act of activation, as is the use of the archives for curatorial research resulting in publications and exhibitions.

It is the primary goal of an archivist to describe a collection in a finding aid in a way that best serves their researchers and facilitates discovery, using the tools developed through prolonged relationship with the material . And likewise, it is the role of the researcher to further activate archival description through the scholarly illustration of connections and context.

About the author

Hannah Mandel is an Archivist specializing in the history of media art, and the institutional histories of contemporary art venues. She is currently the Archivist at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College and the Hessel Museum of Art in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. Her prior roles include the creation of a digital archive for media assets at MOCA Los Angeles, as well as archivist roles at commercial galleries in New York and Los Angeles. She holds a Masters of Library and Information Science from UCLA, and a BFA in Sculpture from the Maryland Institute College of Art. She is the co-curator of the exhibition, “Tony Cokes: Two Works and an Archive,” at the Hessel Museum of Art.

To cite this script

Hannah Mandel, “Processing Fluxus and Media Art Histories: A Case Study of the John G. Hanhardt Archives at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College”. Presentation at the 112th College Art Association Conference, Chicago, within Activating Fluxus, Expanding Conservation session (February 15, 2024). https://activatingfluxus.com/2024/03/06/processing-fluxus-and-media-art-histories-a-case-study-of-the-john-g-hanhardt-archives-at-the-center-for-curatorial-studies-at-bard-college-by-hannah-mandel/.