‘Piano Activities’ (~1962) by Philip Corner – Radio Fluxus: Stories from the Fluxus Archives

Although Philip Corner’s Piano Activities is one of the most emblematic works within the context of early Fluxus, there is a lot of confusion regarding its beginnings and early interpretations, starting with the date of its creation. While literature officially dates the score to 1962, Corner situates its actual writing in the summer of 1961.[1] The piece exists as a typewritten, 3-page set of instructions dated 1962, in the collection of MoMA, NY which it entered as part of The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection.[2] It contains directions for creating sounds on a piano by interacting with different parts of the instrument in unorthodox ways. A shorter version, corresponding to the first page of the complete score, was published in Something Else Press’ 1966 collective volume Four Suits [3] (Fig 1), and much later, in 1990 as a hand-written, serigraphed text in the limited edition Early Fluxus Performance Events (1990) produced by Francesco Conz.[4]

One of the first—and certainly the most notorious and controversial —interpretations of the score took place in Wiesbaden, during the “Fluxus: Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik,” where Piano Activities were performed without the involvement of Corner by Alison Knowles, George Maciunas, Emmett Williams, Benjamin Patterson, Dick Higgins, Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell and others.[5] The festival, a moment of encounter between the European and US associates of Fluxus, unfolded in the auditorium (Hörsaal) of the Städtischen Museum Wiesbaden between September 1-23, 1962. This interpretation was orchestrated by Maciunas and involved the systematic destruction of an old, dysfunctional piano. In a 1978 interview with Larry Miller, Maciunas characterized this act as a pragmatic solution to the disposal of the instrument:

Then at the end we did Corner’s Piano Activities not according to his instructions since we systematically destroyed a piano which I bought for $5 and had to have it all cut up to throw away, otherwise we would have had to pay movers, a very practical composition, but German sentiments about this “instrument of Chopin” were hurt and they made a row about it.[6]

In a conversation with René Block regarding their preparation for the Wiesbaden festival, Ben Patterson and Emmett Williams revealed that they had not consulted the original score prior to their performance:

René Block: But it was an artistic event. It was a piece of music. There was a score…

Emmett Williams: But this piano was destroyed from evening to evening, we were not following a score. The objective was to reduce this thing to nothing. (Laughter)

Ben Patterson: I think as a matter of fact I never saw the original score. … The way we “learned the piece” was through George’s instructions. It was George’s interpretation. He said, well, we’re going to do this piece by Philip Corner and this is the way we do it. And here are your tools, your instruments.

EW: And the instruments were there – a crowbar, hammers, rocks. George’s interpretation. And we assisted, let’s say. And there were saws … I enjoyed it thoroughly.

BP: It was wonderful. And it was a music event. We certainly made sounds – like you’ve never heard before. (Laughter).[7]

The Wiesbaden interpretation left behind extensive documentation, including a short film made for television broadcast[8] and comprehensive photographic records.[9] The piano’s remnants were given new purpose as collectible artifacts, auctioned to festival attendees on the final day. Mercedes Guardado, who participated in the sale alongside the performers, recalled finding multiple buyers in the audience eager to purchase piano keys or fragments of splintered wood with dangling strings for fifty pfennigs each.[10] A significant discovery emerged in 2011 when two audio recordings were found in the archives of Kuniharu Akiyama, a Japanese musicologist and poet.[11] These recordings were subsequently released as a vinyl LP by the Italian label Alga Marghen.[12] When asked about who was responsible for recording Piano Activities in Wiesbaden, Corner stated, “I’m sure it was George. How could it be anybody else but George?”[13] The existence of these audio documents refutes the notion that Maciunas’ interpretation was merely about the practical gesture of disposing of an old piano, suggesting instead that from the outset it was conceived as a sound piece.

The 1962 performance has entered the history of postwar avant-garde art not as an interpretation of a sonic composition, but primarily as an attempt to challenge bourgeois sensibility through a violent act against the cultural symbol of the grand piano.[14] While this interpretation heavily influenced all that followed, Corner himself maintained a perspective that “it was not necessarily the way that it [the score] had to be or should have been performed, even though the score was open enough so that it could have been done that way.”[15] In the artist’s view, the intention of the score was to encourage using the piano as a “total sound instrument” and playing on different parts of it with objects.[16] He stated that “this action is not necessarily intended to destroy the piano, but it doesn’t put a limit [on the interaction]. If you act on the piano with a certain degree of intensity, the piano will break.”[17] Paradoxically, one of the major concerns in the score for Piano Activities was to confront the “’problem of discipline’—improvement, self-discipline, realization—without abridging the free situation.”[18]

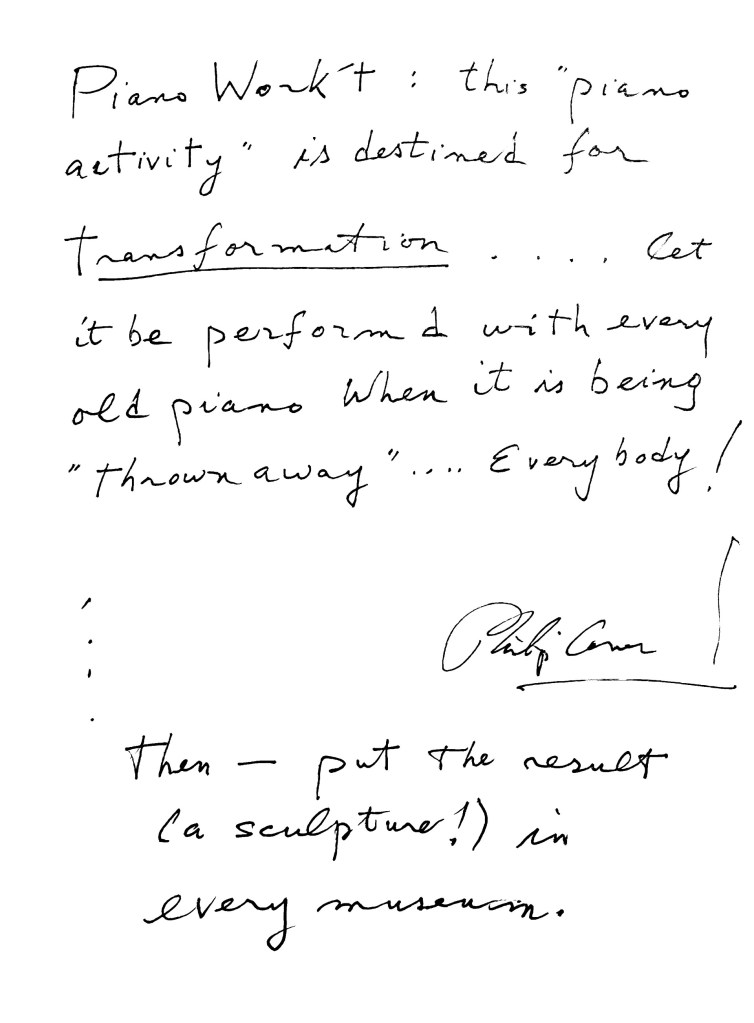

Responding to the legacy of the Wiesbaden interpretation, Corner shifted approach to the work reconceptualizing it as a gesture offering possibilities for transformation that could contextualize and reframe the act of destruction. This transformative approach extends beyond the original focus on producing unconventional sounds through collective action, ultimately converting the piano into a sculptural object that embodies the performance process. As Corner explained, “I think that every piano when it is thrown out should be thrown out that way, like with Piano Activities.”[19] Within this framework, he articulated the concept of the “morality of transformation,”[20] which stipulates that if a piano is to be destroyed, one should begin with an instrument that can no longer function musically.

Corner’s sustained engagement with the piece—and his ongoing confrontation with its Wiesbaden interpretation—spanned over 50 years and resulted in subsequent versions and variations of the score. A notable example is Piano Activities as a Piano Work (2002), written for “The Fluxus Constellation,” a 2002 exhibition at Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Villa Croce, Genoa. This version incorporates a note mentioning “the remaining sculpture,”[21] and its performance actually resulted in such an installation (Fig 3).

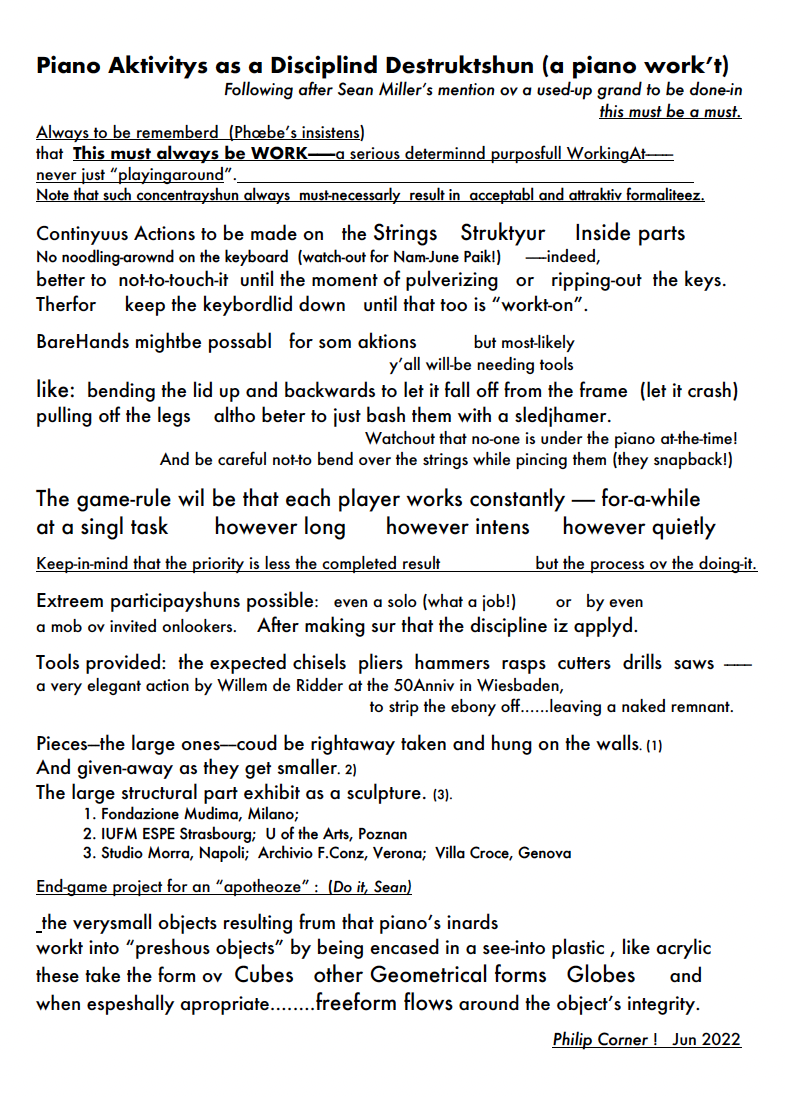

Episode 9 of Radio Fluxus unfolds around yet another variation on Piano Activities, a score titled Piano Aktivitys as a Disciplind Destruktshun (a piano work’t), written by Corner in 2022 and directed to artist Sean Miller. This score is a call for actions [“Do it, Sean”] on the piano structure and inside parts that lead to transforming the piano into wall pieces, sculptures, and small “precious objects” [“endgame”] encased in cubes or globes of transparent resin. The score was performed in 2024, as part of the “Fluxus in the Swamp” exhibitions and performances organized by Billie J. Maciunas and Sean Miller in Gainesville, Florida. The interpretation was filmed and resulted in another transformation: that of a performance into performance documentation that became an artwork in its own right. The resulting film was recently shown as a video installation at Galleria Michela Rizzo, Venice, Italy, in June 2025.

On the occasion of this screening, Sean Miller accepted Radio Fluxus’s invitation to share his experience of interpreting the work sixty-two years after Wiesbaden’s “Fluxus: Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik.” His story reflects on the collective process of performing the score and documenting the performance, as well as transforming a piano through the score’s instructions into various precious art objects—each one embodying and carrying forward the legacy of Piano Activities.

Philip Corner is a visual and sound artist, composer, music theorist, and educator whose interests span from calligraphy to the Balinese-Javanese gamelan tradition. Many of his scores are open-ended, with some elements specified while others are left partially or entirely to performers’ discretion. His notation methods include standard notation, graphic scores, and text scores, and his music frequently explores unintentional sound, chance activities, minimalism, and non-Western instruments and tuning systems. Corner’s career encompasses broad affiliations including participation in numerous Fluxus concerts, exhibitions, and festivals, residency in the Judson Dance Theatre from 1962-64, and later association with The Experimental Intermedia Foundation. He co-founded several ensembles: the Tone Roads Chamber Ensemble in 1963 with Malcolm Goldstein and James Tenney, Sounds out of Silent Spaces in 1972, and Gamelan Son of Lion in 1976 with Barbara Benary and Daniel Goode. As an educator, Corner taught experimental composition at The New School for Social Research in New York and Livingston College in New Brunswick, New Jersey. His work has received recognition through an extensive discography, participation in various exhibitions all over the globe, with scores and poetic works featured in numerous publications and held in major international collections, including The Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

Sean Miller is an artist and art educator based in Gainesville, Florida. He serves as Associate Professor at the University of Florida’s School of Art and Art History, where he teaches Sculpture and Extended Media, among other subjects. Miller’s multidisciplinary practice utilizes intermedia approaches, experimental exhibition formats, storytelling, and speculative design strategies to examine historical events, institutional frameworks, and scientific knowledge. The concept of the archive or cabinet of wonder serves as an organizing principle for many of his projects, reflecting his interest in how knowledge is collected, categorized, and presented. Miller has produced major works and solo exhibitions across diverse media, including photography, painting, sculpture, installation, performance, and web-based work. His practice demonstrates a commitment to collaboration, collective action, multimedia art, relational aesthetics, and alternative art venues, reflecting his belief in art’s capacity to foster community engagement and social dialogue.

Piano Aktivitys as a Disciplind Destruktshun (a piano work’t) was performed on the on September 6, 2024, at the Lyceum Auditorium at Santa Fe College, Gainesville, Florida by Craig Coleman, Jade Dellinger, Bibbe Hansen, Billie J. Maciunas, Jack Massing, Sean Miller, Benedicta Opoku-Mensah, Kyle Selley, and Dan Stepp. The performance resulted in the video titled Piano Aktivitys as a Disciplind Destruktshun (a piano work’t) by Wes Kline in collaboration with Sean Miller, Chad Serhal and Sejoo Han.

[1] Corner has mentioned on various occasions that the actual date of writing Piano Activities is summer 1961; see: UF College of the Arts, dir. UF School of Art + Art History Visiting Artist Lecture with Philip Corner. 2021. 01:08:44; 23’46”, https://youtu.be/wYCgI1rJ21E?t=1425 and also Hölling et al., “On Creativity as Discovery—A Conversation with Hanna B. Hölling, Aga Wielocha and Josephine Ellis.”

[2] Corner, Philip. “Piano Activities.” 1962. MoMA, NY. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/127342.

[3] Corner et al., The Four Suits.

[4] https://www.fondazionebonotto.org/en/collection/fluxus/cornerphilip/574.html

[5] On various occasions Corner stated that Piano Activities were performed at the concert at Judson Memorial Church before the Wiesbaden Festival. See: Corner, “Oral History Interview with Philip Corner.” and Hölling et al., “On Creativity as Discovery—A Conversation with Hanna B. Hölling, Aga Wielocha and Josephine Ellis.”

[6] Williams and Noël, Mr. Fluxus: A Collective Portrait of George Maciunas, 1931-1978, 53.

[7] Williams and Noël, Mr. Fluxus: A Collective Portrait of George Maciunas, 1931-1978, 54.

[8] “Beitrag: Fluxus Festival in Wiesbaden.” Hessenshau, October 9, 1962. https://www.ardmediathek.de/video/hr-retro-oder-hessenschau/fluxus-festival-in-wiesbaden/hr/Y3JpZDovL2hyLW9ubGluZS8xMzY0MzY

[9] See e.g.: photographic documentation by Hartmut Rekort held in the collection of Sohm Archive at Staatsgalerie Stuttgart.

[10] Stegmann, “The Lunatics Are on the Loose …”: European Fluxus Festivals 1962-1977, 73.

[11] Haruta, “Splinters, Ashes, Dirt: Piano Destruction and Creative Opportunity.”

[12] https://www.soundohm.com/product/piano-activity

[13] Corner, “Oral History Interview with Philip Corner.”

[14] The motif that Corner contests: “And it has nothing to do with negativity, attacking the bourgeoisie, protesting against the historical ‘blah blah.’“ Hölling et al., “On Creativity as Discovery—A Conversation with Hanna B. Hölling, Aga Wielocha and Josephine Ellis.”

[15] Williams and Noël, Mr. Fluxus: A Collective Portrait of George Maciunas, 1931-1978; see also: Philip Corner: On Creativity as Discovery—A Conversation with Hanna B. Hölling, Aga Wielocha and Josephine Ellis.

[16] UF School of Art + Art History Visiting Artist Lecture with Philip Corner. 29’43”

[17] Hölling et al., “On Creativity as Discovery—A Conversation with Hanna B. Hölling, Aga Wielocha and Josephine Ellis.”

[18] Philip Corner, “Impositions of Order,” in Corner et al., The Four Suits.,163; see also Stark, “Passionate Expanse of the Law: Intermedia and the Problem of Discipline.”

[19] Corner, “Oral History Interview with Philip Corner.”

[20] A text under this title forms part of the sculptural installation resulting from the performance of the score that forms part of the collection of the Villa Croce Museum in Genoa. See: Hölling et al., “On Creativity as Discovery—A Conversation with Hanna B. Hölling, Aga Wielocha and Josephine Ellis.”

[21] https://www.fondazionebonotto.org/admin/download/file/f6ccf4c_fxm03922.jpg

References:

Corner, Philip. “Oral History Interview with Philip Corner.” Interview by Luciana Galliano and Toshie Kakinuma. September 20, 2015. https://www.kcua.ac.jp/arc/ar/philipcorner_en/.

Corner, Philip, Alison Knowles, Ben Patterson, and Tomas Schmit. The Four Suits. Edited by Dick Higgins. Something Else Press, 1965.

Haruta, Devanney Turpin. “Splinters, Ashes, Dirt: Piano Destruction and Creative Opportunity.” Master thesis, Wesleyan University, 2021. https://digitalcollections.wesleyan.edu/_flysystem/fedora/2023-03/17042-Original%20File.pdf.

Hölling, Hanna B, Philip Corner, Aga Wielocha, and Josephine Ellis. “On Creativity as Discovery—A Conversation with Hanna B. Hölling, Aga Wielocha and Josephine Ellis.” [forthcoming] In Activating Fluxus, Expanding Conservation, edited by Hanna Hölling, Aga Wielocha, and Josephine Ellis. Routledge, 2026.

Stark, Trevor. “Passionate Expanse of the Law: Intermedia and the Problem of Discipline.” In Call It Something Else: Something Else Press, Inc. 1963-1974, edited by Christian Xatrec and Alice Centamore. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía Madrid, 2023.

Stegmann, Petra, ed. “The Lunatics Are on the Loose …”: European Fluxus Festivals 1962-1977. Down with Art!, 2012.

UF College of the Arts, dir. UF School of Art + Art History Visiting Artist Lecture with Philip Corner. 2021. 01:08:44. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wYCgI1rJ21E.

Williams, Emmett, and Ann Noël, eds. Mr. Fluxus: A Collective Portrait of George Maciunas, 1931-1978. Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Sources of the additional sound used in this episode:

at 3:05: Gorge Maciunas’ voice commenting on the 1962 Wiesbaden performance of Piano Activities. Source: Interview with George Maciunas by Larry Miller, 1978, film, 60 min, b&w, sound.

at 4:21: Excerpt from the TV broadcast: “Beitrag: Fluxus Festival in Wiesbaden.” Hessenshau, October 9, 1962.

+ various excepts form the sound recorded during the 2024 performance of Piano Aktivitys as a Disciplind Destruktshun (2022) in Gainesville, Florida. Courtesy Sean Miller.

Featured image: Piano Aktivitys residues; “Fluxus in the Swamp” exhibition (2024) at the Santa Fe Gallery, Gainesville, FL. Photo by Sean Miller.