by Weronika Trojańska

“These are preparations I used in my performances 1961–1982 throughout the world of 26’1.1499’’ for a string player by John Cage,” states the handwritten inscription on an old, battered suitcase that was sent to Italian collector and publisher Francesco Conz, signed: Charlotte Moorman. The suitcase hides all kinds of treasures. From an evening jacquard gown, pumps slightly covered with mildew, to music scores and invitations for Moorman and Nam June Paik events, up to a decrepit newspaper from 1961, a soldering tool, and a faded candy wrapper, it resembles a bit of portmanteau that might have spent years in someone’s attic. Today it is stored in Archivio Conz in Berlin, which houses artworks, documents, and editions of Fluxus, Lettrism and Concrete Poetry left behind after Francesco Conz death (Fig. 1).

26’1.1499’’ for a string player (1953-55), titled after its duration, is a part of Cage’s series of works that he liked to call “Ten Thousand Things.” The graphic notation’s complicated and calculated structure didn’t stop Moorman from performing the piece on many occasions (often assisted by Paik), even if, according to various sources, she never managed to play it within the time limit indicated (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). While some of those performances are traceable through photographs and archival materials, others are not, as they probably happened only in front of the eyes of the spectators, or in even more private settings.

As noted by Lisa G. Corrin, 26’1.1499’’ became Moorman’s magnum opus to the extent that she used to carry a highly annotated copy of the original score around with her during her travels.1 Inspired by Cage’s instruction that “the lowest area is devoted to noises on the box, sounds other than those produced on strings. This may issue from entirely different sources e.g. percussion instruments, whistles, radios, etc.,”2 Moorman treated the score as a canvas for expressing her own creative ideas. Embellishing it with personal commentaries, often with drawn hearts, glued cut outs from magazines (like an advertisement for tampons), or fragments of adhesive tape or Band-Aids, it became her “aide-memoire, a road map, and a diary.”3 But this very score, resembling more of a collage or a pop version of a drawing by Cy Twombly, is held in the Charlotte Moorman Archive at the Northwestern University Library, while the one from Conz’s suitcase lacks Moorman’s notes entirely. Did the latter have a specific role? If so, what was it? Or is it a prop or an artefact, meant only to be exhibited and not performed? Or at least, not by Moorman.

Placing the musical notation together with the variety of objects in a designated travelling bag and sending them over to Italy (which is a performative act itself), makes me think that Moorman was making a deliberately artistic gesture, and maybe even thinking of the suitcase’s possible future display. Intentionally or not, the suitcase and its contents resembles a portable museum of past performances of 26’1.1499’’—performances that may or may not ever have happened. Bearing in mind that Conz was the Fluxus fetishist,4 and Moorman was herself a passionate hoarder, this artistic gesture resembling the Duchampian La Boîte-en-valise5 somehow makes sense. Even more so when we look at the photographs held in Archivio Conz depicting a pile of seemingly random items laid out on the blue-painted floor, among which is also that very suitcase (Fig. 4). Placed open on the ground, the suitcase is filled with colourful, now-deflated toys. In front of the suitcase lies a folded dress and a pair of pumps, and, to their right, is Cage’s sheet of music. The suitcase is surrounded by a variety of even stranger objects that resemble those Moorman mentioned on, for example, a poster promoting her performance in Philadelphia in 1966: “You will see and hear a human cello, a film of Cage and Miss Moorman, records of rock and roll and jazz […] aluminum sheets, pie pans, hammer, drumsticks, […] pistol, […] toy whistle, Halloween whistle and siren whistle, […] crow call, squirrel call […] mixers, amplifiers, speakers.”6 Or the ones she used for her performance of Cage’s piece at WNET-TV studio in 1973 (including the same toys). From the images found in Archivio Conz, it seems that an important part of the setup was also a standing frame that looks a bit like a clothing rack, with objects placed on top of it as well as hanging from the upper bar, like Coca-Cola cans or a wooden wind chime, which replaced the percussion rack that she used during the live events.

The photograph is somewhat reminiscent of images taken by the police. More, specifically, they might be compared to photographic evidence of items found at a crime scene. It seems that they are a documentation of things Moorman possibly used for performances of 26’1.1499’’. Were these objects used in one specific performance or are they a compilation of many items that she performed with on several occasions? Comparing the photographed toys and different things to other testimonies of Cage’s piece performed by Moorman in various archives and books, the first option seems less plausible. Most of the objects from the photographs could be also found in boxes stored at Archivio Conz, though perhaps they were not necessarily acquired directly by Conz for his collection and most likely came from Moorman herself. This is particularly significant given that she not only gifted Conz the suitcase, but also many other personal items in the hopes that he would establish her estate.

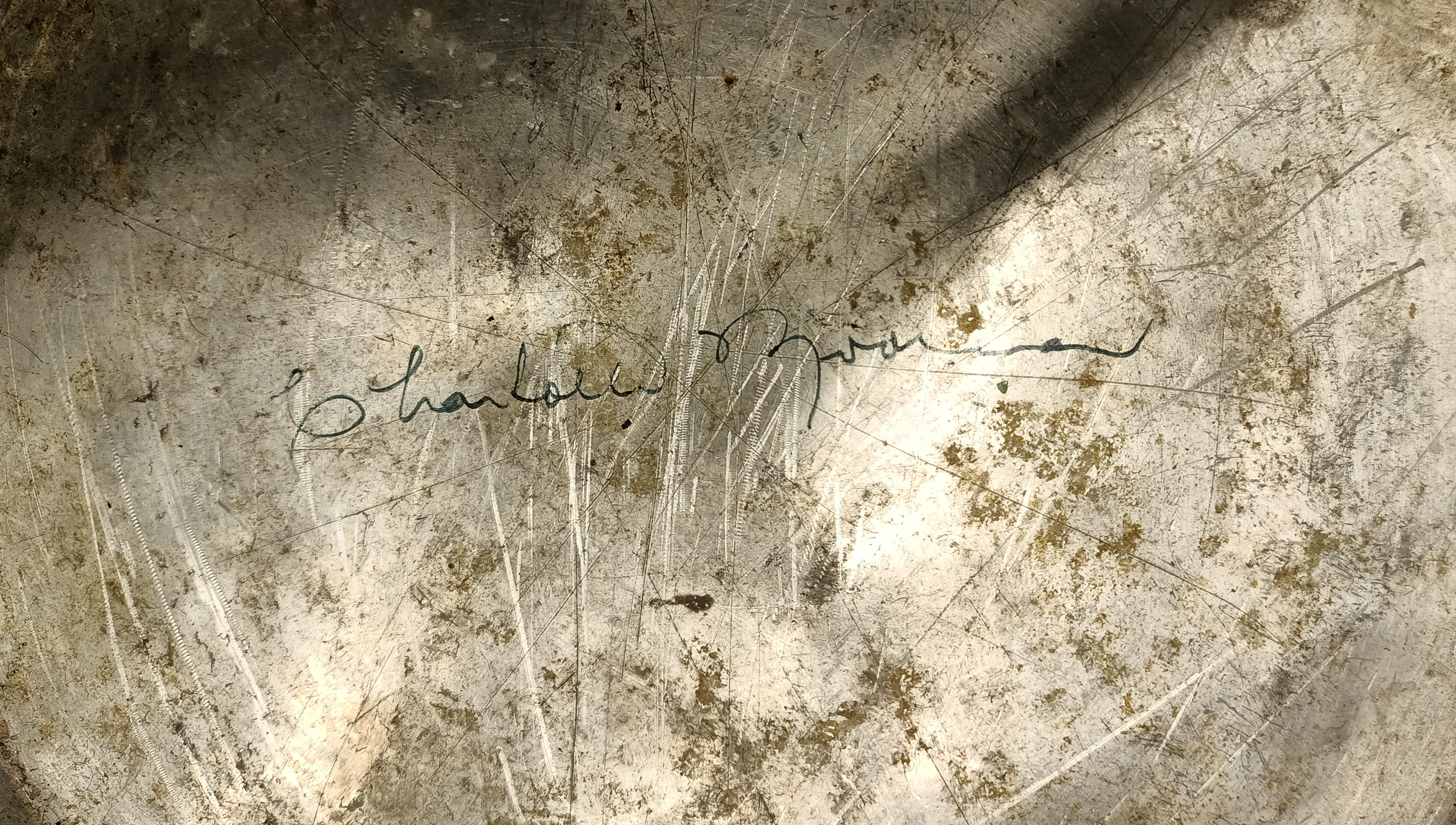

The rest of the objects remain even more of a mystery. According to Patrizio Peterlini, director of the Bonotto Foundation, the lack of inscriptions on the box containing Moorman’s objects seems unusual: “Francesco, being obsessive, always wrote down what it was (even if sometimes not very clearly except to himself).”7 Nevertheless, the items share the “fetishistic sensibility” of the collection, carefully placed back in their original packaging (like a whole bunch of plastic instruments for children or toy guns) and/or signed by Moorman herself, including even the hammer handle or corroded metal plate (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). Things get a bit more intricate when you realise that there are more photos of these peculiar objects in the exact same arrangement now photographed in a gallery setting, with wallpaper consisting of photocopied ephemera of Moorman and Paik’s shows (some of them come from editions of Conz and Rosanna Chiessi’s “Pari & Dispari”) in the back and some photographs from their performances on the adjacent wall (Fig. 7). The other photos that appear to have been taken during the same exhibition show other works, primarily by another Fluxus artist Joe Jones, like his well-known Music Bike No.3 (1977) and his other sound sculptures, together with prints and photos. It seems that all of these pieces also belong to the Conz collection and all deal with the notion of music in their own ways, thus the exhibited works complement each other very well. Nonetheless, there is no traceable evidence of where this exhibition of Jones and Moorman, as seen in Conz’s photographs, took place.

When asked about the circumstances of these photographs, Fluxus artist Eric Andersen maintained: “I don’t recall having attended this show. However, I’m pretty certain that it was in Germany in the ‘80s.8 If I see the visitors, the young boys, it couldn’t have happened in Germany. Probably it can be Italy, Poland or former CSSR,”9 replied gallerist Christel Schüppenhauer. When asked the same question, another Fluxus artist Ann Noël responded: “I presume that these photos were taken by Francesco Conz, and were made during his visit to the USA in 1974.”10 The closest anyone came to recognising the show was gallerist Caterina Gualco:“I think that all this stuff are remains of Charlotte’s performance in Asolo.”11 So far, there is no further documentation or testimony of it that I could find. Most of the people asked about the exhibition shared the same view: as put by Mieko Shiomi, “I have no idea about the photos you sent me”.12

Regardless of what it was and where it took place, within the framework of the show, the arrangement of Moorman’s stuff becomes a sculptural object in its own right. It could even appear as a installation of remnants of her interpretation of Cage’s composition. However, while Jones’ sculptures invited the audience to activate the sound, Moorman’s relics don’t wait to be reanimated. They were not meant to be touched. Those very same objects linger today locked up in boxes, sharing a similar life of performance leftovers. The difference is that when they were exhibited in a gallery, visitors could have seen them by chance, whereas today the viewing is usually done intentionally by researchers.

The array of objects chosen by Moorman for 26’1.1499″ can be easily seen as a commentary on the contemporary times in which she performed this composition. Using emblems of the 1960s and 70s she clearly states that her interpretation of Cage’s piece from the 1950s “is very American-a kind of pop music”13 and thus, even if it wasn’t very faithful to the original, becomes a new musical arrangement. Using everyday objects and giving them a new purpose, as well as finding a new application for her cello, Moorman made a Fluxus version of Cage’s composition. In that context can we ask whether her renditions of 26’1.1499’’ was more of a performance/realization of a musical score, a concert or an art piece? Or simply by being at the intersection of these formats, Moorman’s rendition of 26’1.1499’’ enters the realm of visual art as other Fluxus music-inspired works.

But what can this “installation” tell us then, apart from the fact that those were the objects supposedly activated in Moorman’s performance(s)? Does it show us that she theatricalized 26’1.1499’’ and, following curator Joan Rothfuss, “transformed it into a situation comedy of sounds and sights- hence the egg frying, the pistol shot, the bomb, and the belches, as well as the purely decorative balloons”?14 Can we guess on the basis of the photographs of used objects that Cage was not very fond of Moorman’s interpretation to the point that his publisher wished her dead?15 That might have been the case, perhaps, if someone knew Cage’s original version. But what if not? Not everybody has seen the recorded TV shows of Moorman and Paik performing the piece or has read Benjamin Piekut’s essay addressing the history of the Moorman-Cage relationship in detail.16 What is the afterlife of these archived objects, besides that they can be seen, touched (carefully with gloves), smelled, conserved, remembered and reimagined? (Fig. 8).

Polysemous objects have a performative quality. The potential sounds of these items used by Moorman, when activated, can easily be imagined or mentally recreated. The objects invoke all sorts of noises, even while being completely silent. It’s like when you think of a musical instrument and you can hear the sound it produces in your head. When you look at a hammer you might know what kind of clang it can make, or seeing a whistle, you may hear in your head one you played as a child. Maybe this sound or image that pops up in our heads, it’s the aftermath of something we heard or saw at some point in our lives, or that we will hear or see in the future.

Studying the objects gathered at Archivio Conz, I can’t help but imagine Moorman carrying a cello case, big enough to have to book an extra seat on the plane, along with voluminous bags full of intricate stuff. She does so from one performance venue to another, from one country to the next. She wears her gown, pumps, and impeccable hairstyle. She is alone or with her companion Paik. She renders Cage’s 26’1.1499’’ more popular than he could have ever imagined.

- Lisa Grazione Corrin and Corrine Granof eds., A Feast of Astonishments: Charlotte Moorman and the Avant-Garde, 1960s-1980s (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2016) ,viii, ix. ↩︎

- Lisa Grazione Corrin and Corrine Granof eds., A Feast of Astonishments, viii. ↩︎

- Ibid, ix. ↩︎

- Francesco Conz was known from collecting not only Fluxus art works but also other ephemera touched by the artists, like handwritten notes, napkins or even underwear. These belong to his “Fluxus Fetish” collection. ↩︎

- Portable suitcase assembled by Marcel Duchamp containing his entire body of work reproduced as 69 miniature replicas. Between 1936 and 1941 around 300 of them were produced. ↩︎

- Benjamin Piekut, Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits (California: University of California Press, 2011), 156 ↩︎

- Personal email correspondence with Peter Peterlini, September 19, 2023. ↩︎

- Personal email correspondence with Eric Andersen, August 21, 2023. ↩︎

- Personal email correspondence with Christel Schüppenhauer, September 16, 2023. ↩︎

- Personal email correspondence with Ann Noël, August 21, 2023. ↩︎

- Personal email correspondence with Caterina Gualco, September 11, 2023. ↩︎

- Personal email correspondence with Mieko Shiomi, August 22, 2023. ↩︎

- Feast of Astonishment, 137. ↩︎

- Joan Rothfuss, Topless Cellist: The Improbable Life of Charlotte Moorman (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017), 2. ↩︎

- Benjamin Piekut, Experimentalism Otherwise, 150. ↩︎