Magdalena Holdar of the Department of Culture and Aesthetics at Stockholm University presented insights from her recent research at the 112th College Art Association conference in Chicago. Her paper, titled “Fluxus Bit by Bit: The Great Bear Pamphlets – Reactivating Fluxus through the Medium of Publication,” was featured within the session Activating Fluxus, Expanding Conservation, organized by our research team on February 15, 2024. Below we have made the presentation available to everyone who was unable to attend the conference.

There is a tension in the research around Fluxus that is interesting to observe, and that has to do with things, or the absence of them. This tension might even stem from Fluxus’s character – being on the one hand almost fixated with scraps of paper, food, and everyday objects, while at the same time also gravitating towards performance and something more evasive, that cannot be contained in “stuff”. The question, which I will explore in this presentation, is: how can we capture these two sides of the Fluxus coin in a way that acknowledges the value of both of them? My material will be one that is both a thing and something more ephemeral and elusive; something that was distributed broadly, but is impossible to track its influence other than through indirect traces, hunches, and guess. My paper deals with The Great Bear Pamphlets.

Researchers who primarily have the things in Fluxus, such as kits, posters, written scores, and the like, in the centre of their investigations, make careful notations of artworks and their origins, authors, and circulation. We find the results of their endeavours in archives, publications, and exhibitions. The archivist Jon Hendricks, curator for the vast Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, now at MoMA, has devoted decades to mapping Fluxus art and artist, and we can all benefit from his meticulous archival work and informed writings. This line of Fluxus research builds solid results based on verified activities and material facts, establishing and anchoring, even stabilizing.

However, this strict application of an archival methodology risks obscuring other aspects of Fluxus, that arguably are just as important: the artists who performed the works by others, or weren’t among George Maciunas’s closest allies, or who tended to cross the porous border that separated Fluxus from something else.

So here we have the other end of the spectrum of Fluxus research: the one that takes the doing as its starting point, rather than the material artefacts that have sometimes, but not always, remained. We often find the artists themselves in this category, Emmett Williams being one example. In his autobiography My Life in Flux and Vice-Versa, he writes, apropos the manifold compilations of Fluxus scores and event notations:

To concentrate on the short form style in such a compendium would give no idea of what really went on during the early Fluxus festivals in Europe […].

There is, according to Williams, an element in Fluxus that is lost when we try to pin it down, to apply the traditional collections management approach to archival collections.

What do we find when we explore that spongy Fluxus wetland of unknown performativity— so complex to explore and yet so crucial to our understanding of how Fluxus has operated? Is reactivating Fluxus equal to centring the material objects, the written texts, and the verified facts around an event? Or can we assume that Fluxus was and is being constantly re-activated, via channels that are not tracked or traced or even possible to see other than through their effects, the results of which demand other modes of analysis and research.

WHAT WE KNOW

Let’s investigate a material that oscillates between these to ‘extreme’ positions that we can call the archival and the performative. Dick Higgins, an eclectic thinker, skilled collaborator, and a sharp theorist, decided around the time for Fluxus’s formation in the early 1960s, to invest his substantial family inheritance in a publishing house: The Something Else Press. The idea was to provide a platform for avant-garde and neo-avant-garde material that targeted a broad audience, beyond the limited souls who already accessed it through existing, but limited, artist’s outlets, such as DIY-publications and limited-edition materials. Books made by Something Else Press, Higgins thought, would, thanks to using competitive distribution channels, reach beyond the communion of already saved avant-garde souls. The drawback, as it turned out, was that many avant-garde souls did not feel they could afford the Something Else books. Higgins’s solution was to make inexpensive ‘miniatures’ of them: the Pamphlets.

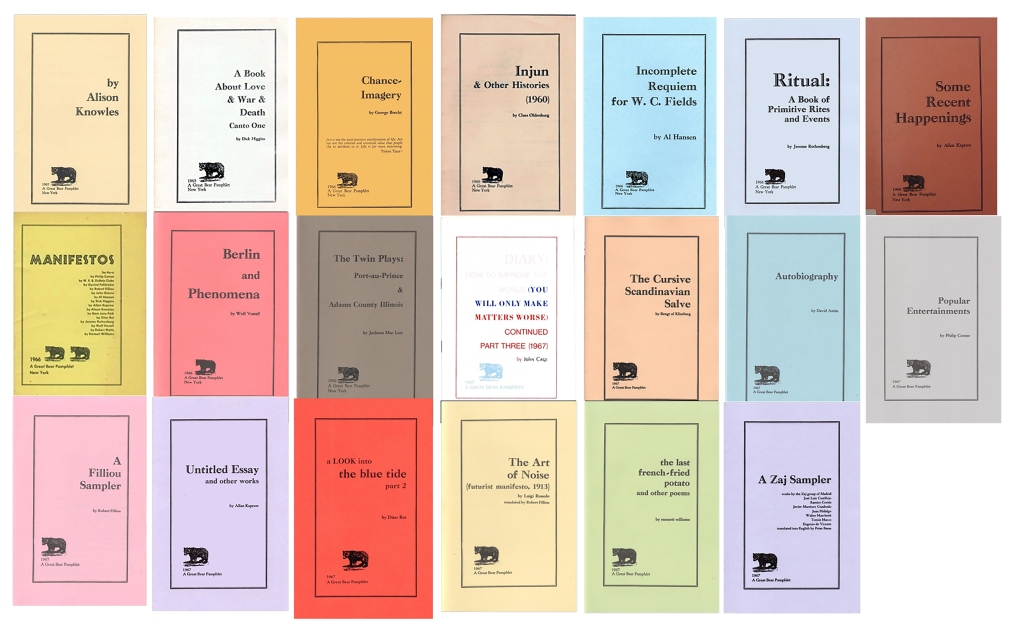

There are 20 issues in the Great Bear Pamphlet series. They all have similar design: a standing format, a black border, within which we find the title, in a large font size, and the name of its author, much smaller. Title and author are set to the right, rather than centred, and in the left bottom corner there is the drawing of a bear. Under it, the year of publication and the title of the series. All issues except one are 16 pages, adapted to exactly fit the printer’s standard sheet of paper, which was 8 ½ by 11 inches. The Manifestos issue, however, is 32 pages long.

The content of each issue is however completely different and would lead the recurring reader down a different avenue each time. Never really specifying that they move within the realm of Fluxus, they still present—or represent—Fluxus, issue per issue; bit by bit. The Pamphlets, it seems to me, drafts Fluxus theory, methodology, and even historiography through their varied content. In addition, they work as an illustration of (or maybe method for) Dick Higgins theoretical explorations. The list of authors that were granted an issue in the series, such as Alison Knowles, Allan Kaprow, George Brecht, and Bengt af Klintberg, were all among his close friends (and in Knowles case family). In fact, Higgins’s autobiography Jefferson’s Birthday from 1964, petty much drafts the forthcoming list of authors for his Great Bear Pamphlets.

We know quite a few things about how the Pamphlets existed in the world, although research about them is limited:

- We know that readers could buy them in book stores, and even in a supermarket in California, or order them directly from Something Else Press in New York.

- We know they were very cheap, ranging between 40 and 80 cents, and marketed through another of Dick Higgins’s channels, The Something Else Press Newsletter: “These are the least expensive major documents in the new art forms; without them, it costs a fortune to be informed”

- And we also know that a digital version of the complete series is accessed for free at Ubuweb.

BUT: we cannot know exactly how each issue behaved once released from the press and distributed to its readers. We cannot, other than indirectly, determine their performativity, and we lack tools to trace the readership of the series.

The effect of each issue can mainly be revealed through personal narratives and hearsay. Indeed, these pamphlets and how they came to operate in the world, evade hard evidence, but embrace the creative, micro-level activities that Fluxus also spurred, under the radar. How can we account for this richly fertile but largely invisible activity?

WHAT WE DON’T KNOW

As the quote from Emmett Williams suggests, two of the most central signifiers in Fluxus art and practice—its fluidity and evasiveness—sit a bit uneasy with the material remains, such as texts and artefacts. They might have been that which spurred activity, but they are also (quite often and quite clearly), oftentimes subordinate to the (documented) activities. The things, as they have remained, suggest a broad scaffolding of events and relations. But they have also left plenty of room to that we cannot know.

When it comes to printed matter in Fluxus, one can easily feel reassured that they are what they are: stable entities; easily archived; recognisable format. The Great Bear Pamphlets are all these things and are often also used in research as source materials because they function as live archival materials, the representation of past events, a kind of mini-history. But they do more than that. They are also, as I see it, the manifest border to a vast marshland, where the art of movement, flow, and micro activity, point to the fact that the traces we have from Fluxus events and the like are only fragments. Nonetheless, this Fluxus mire is also where the art continues to perform, reinvent itself, and is being re-activated. There is some evidence of the Pamphlets’ performative effects, and how they might have operated in this big unknown. In order to catch that, we need to acknowledge the validity of soft sources, such as oral narratives and indirect evidence, and perhaps even the creative intuition on the part of scholars. Far from an emptiness, the wetland suggests a performative fullness.

Let me present a first example of the impact the Great Bear Pamphlets has had, and how it, in turn, points to a Fluxus mire with micro-level activity. Bengt af Klintberg, the Swedish folklorist, Fluxus artist, and close friend of Dick Higgins, was invited to produce an issue for the series in 1967. “The Cursive Scandinavian Salve” contained many of af Klintberg’s earlier works, now translated into English, as well as some spells that he had come across in his academic research.

Although af Klintberg had participated in several Fluxus events previously, and also arranged them in Sweden and Norway, the Cursive Scandinavian Salve was his first internationally published work in this context. Soon afterwards, his works were performed in New York, and he was also invited to participate in international events on a regular basis after this. In 1970 he was contacted by a group of New York based artists for a collaborative project, called World Works. He had never met them, nor heard from them before, which suggests that they could very likely have come across his work via the Pamphlet.

Secondly, according to Ken Friedman, the format of the pamphlets allowed further photocopying and he claims they were continuously multiplied in colleges, universities, and even libraries. There might not be any clear evidence of this statement, but it sounds plausible because it is also in line with Dick Higgins’s objective with the series—to spread the work of these artists to audiences beyond the hardcore fans of the neo-avantgarde—that is, toward a readership that wouldn’t consider writing to Something Else Press to order a copy. Knowing how we share materials in our everyday lives, lending, copying, or giving away to someone likeminded, it is fair to assume that this is exactly what happened to these issues, maybe even because the price was low and the format modest and that they almost begged to be reproduced, photocopied, cut up, etc and distributed in new networks.

This everyday activity of sharing and gift giving stuff of mutual interest is one activity that has certainly been going on in that mire, where facts are scarce and traces faint. Letters between Fluxus artists show that there is a constant exchange of materials: reviews, exciting articles, invitations, etc. The effects, that is, their performativity, of them might however be untraceable.

Acknowledging, finally, this lack of hard evidence and embracing the awareness that this vast wetland is packed with activity means that we need to leave any ideas of a Newtonian cause- and-effect in this material behind. A text, or an artwork, can lie dormant in there for a long time before it begins to perform. Activities might simmer for years before they are noticed, if they ever are. An artform that is rather an “attitude and philosophy of life” moves differently and often under the archivist’s empirical historiographical radar. As such, the question can be asked, has Fluxus ever not been active? Or is it Fluxus as research material and historic object that needs to be re-activated?

Ken Friedman has described the Great Bear Pamphlets as one of Higgins’s “evangelical projects, designed to spread the Fluxus gospel”. This is a good metaphor, all in tune with their art of agency. Gospels perform and reperform the word. They engage believers and find new members to their congregation. Unlike the site specificity of chapels/galleries, they activate and reactivate, and they travel, possibly in perpetuity. Much of their performativity happens over time, unnoticed, and leaving but the faintest of traces.

About the author:

Magdalena Holdar is associate professor of art history and curatorial studies at Stockholm University. As a researcher of Fluxus, she has published articles on its theory, methodology and collaborative strategies, in articles as well as in the monograph Fluxus as a Network of Friends, Strangers, and Things (Brill 2022).

To cite this script:

Magdalena Holdar, “Fluxus Bit by Bit: The Great Bear Pamphlets,” presentation at the 112th College Art Association Conference, Chicago, within Activating Fluxus, Expanding Conservation session (February 15, 2024). https://wordpress.com/post/activatingfluxus.com/3062.