“No idea is clear to us until a little soup has been spilled on it”.

Higgins, Dick. “A Something Else Manifesto by Dick Higgins.” In Manifestos. Great Bear Pamphlet. New York: Something Else Press, 1966.

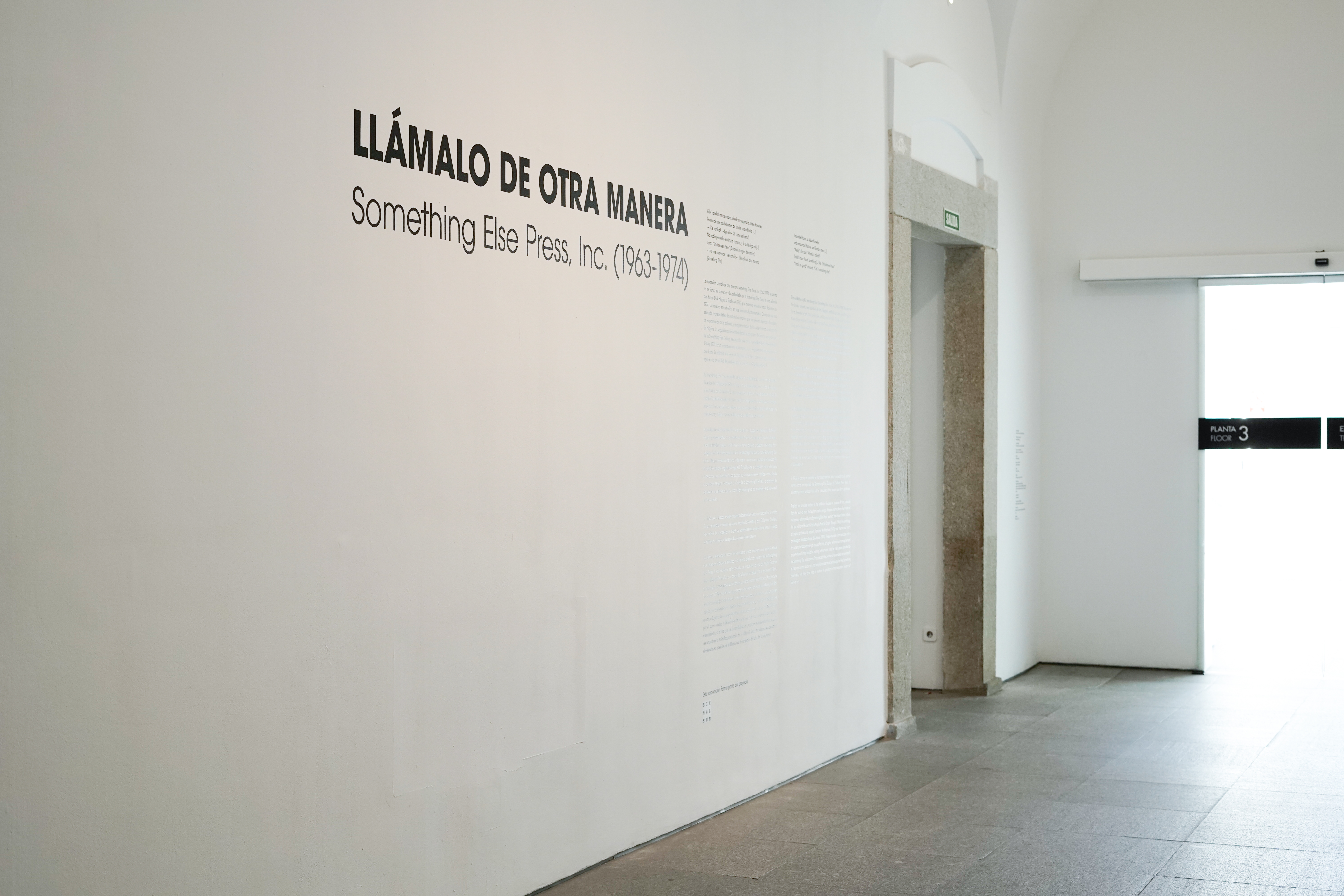

On September 26, 2023, the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid celebrated the inauguration of an exhibition titled “Llámalo de otra manera / Call It Something Else: Something Else Press, Inc. (1963-1974),” curated by the New York-based duo of curators, Alice Centamore and Christian Xatrec. The exhibition focuses on the books, projects, and activities of Dick Higgins’s publishing house Something Else Press, advocating for its acknowledgment as a pivotal hub of contemporary American art during that era.

entrance to galleries at the Sabatini building.

Something Else Press was founded in 1963 by Dick Higgins, an American artist, composer, theorist, poet, and publisher. Together with other founding artists of the Fluxus network, Higgins attended John Cage’s course in experimental music at The New School and participated in the inaugural Fluxus activities in Europe in 1962 and 1963. Those experiences were formative for his art practice and the development of his theoretical thinking about the potential and nature of art. Operating until 1974, Something Else Press became one of the most important projects in Higgins’s artistic portfolio, encompassing a diverse range of activities. Aside from conceiving and publishing books, the Press was disseminating new ideas about art through its Something Else Newsletter, printing and distributing pamphlets compiled in the Great Bear Pamphlet’s collection and organizing exhibitions and other art events in the Something Else Gallery. All those multifaceted activities shared a common goal: to provide a platform for the dissemination of innovative work by a wide array of artists and thinkers, with the overarching aim of ensuring that their ideas could endure and continue to evolve.

If one were to approach Something Else Press as a work of art or an art project that Higgins was collaboratively realizing alongside many other artists, the Museo Reina Sofía exhibition could be viewed as a ‘one-work show’ that both showcases and maps its various phases, expressions, participants, and outcomes. Starting with this premise during my visit to the exhibition, I considered the curatorial work in a twofold manner. First, I examined how they grappled with the challenge of presenting this complex, processual work to the public while preserving its multidimensional and collaborative nature. Second, I observed how they addressed the conundrum of presenting the kind of art that is often considered to have transcended traditional objecthood, relying heavily on the book format and language, within the confines of an art museum gallery. This entails filling the spaces originally intended for and expected to showcase autonomous art objects, created through a deliberate gesture at a specific moment in time, with text-based materials, evidence of collaborations, and works that were meant to organically evolve, remained unrealized or underwent transformations into something else.

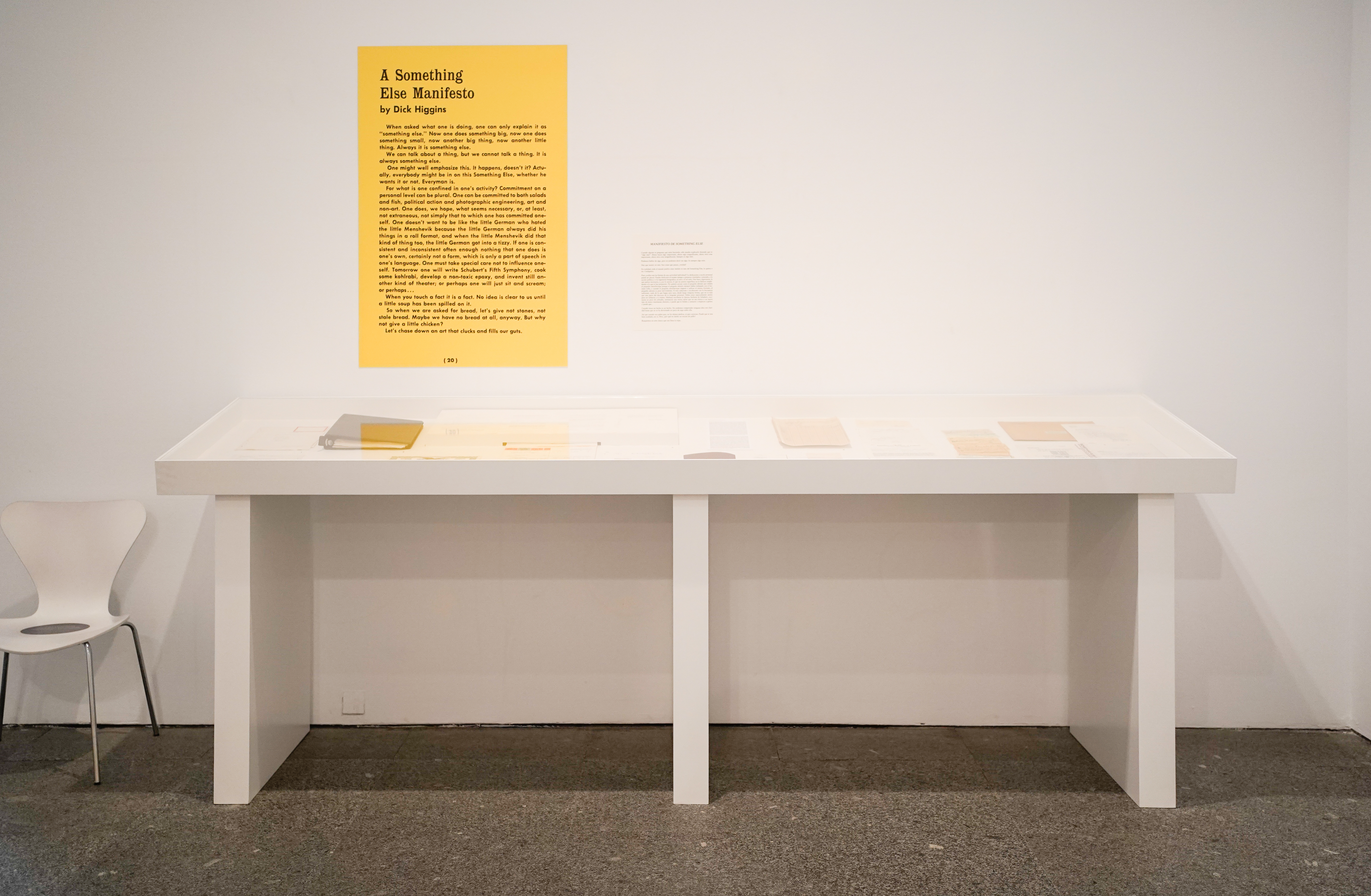

The exhibition is structured into three main sections, with the initial one showcasing the total output of Something Else Press, including unrealized projects and theoretical contributions. The narrative starts with a presentation of A Something Else Manifesto (New York, 1964), published by Higgins in one of the Great Bear Pamphlets. This whimsical and somewhat enigmatic text playfully hints at what visitors can anticipate in the following rooms of the show, encompassing a wide array of engagements (“For what is one confined in one’s activity?”) and their frequently unforeseen results (“So when we are asked for bread […] why not give a little chicken?”). Beneath it, a display case features a selection of documents offering insights into the establishment of the publishing house as a legal entity and a functioning business. Alongside shedding light on the financing and management of the Press, these documents also introduce the names of several of Higgins’ fellow artists and friends who play pivotal roles within the Press and will continue to appear prominently in the subsequent rooms of the exhibition. This serves as another indication of what lies ahead: the Press is not the work of a sole individual but rather a collaborative effort involving a diverse range of personalities.

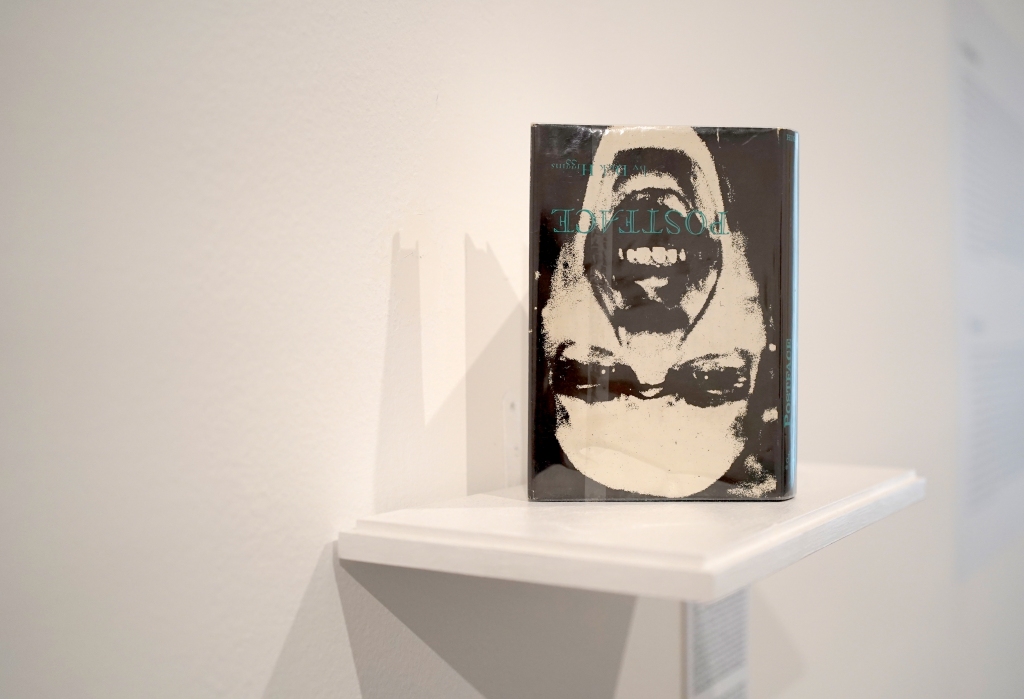

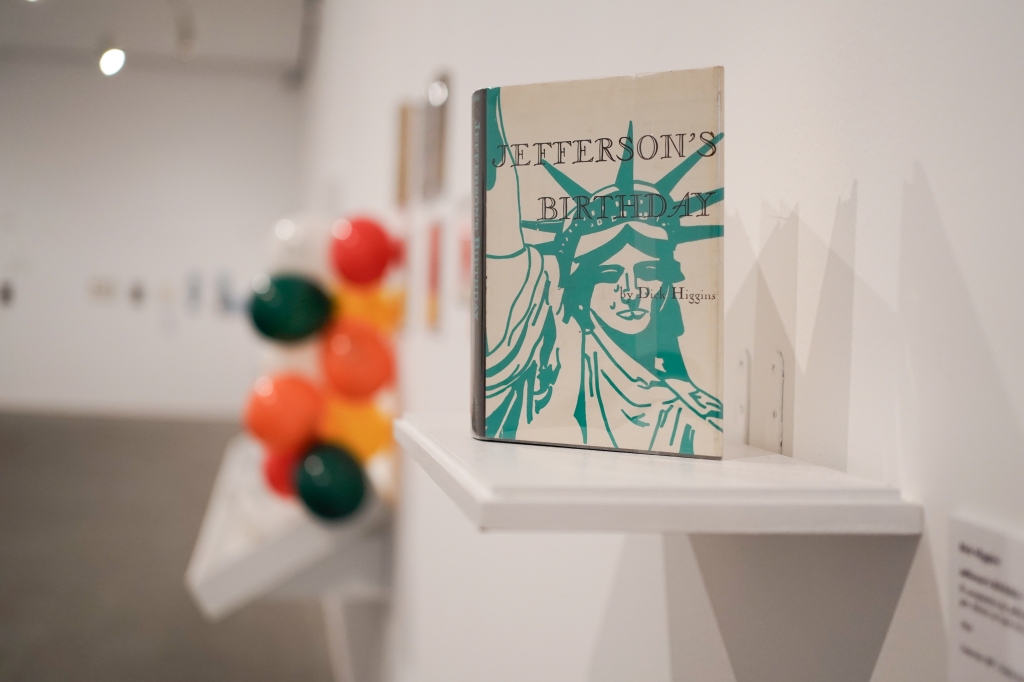

What follows is a detailed presentation of the publishing house’s undertakings, organized chronologically through the lens of the books it produced. It all begins with Higgins’s Jefferson’s Birthday/Postface (New York, 1964), a book project initially intended to be published by George Maciunas under the Fluxus imprint. However, due to Maciunas’ reluctance to prioritize the delayed publication, a disagreement arose between the two artists, which led to Higgins’s decision to establish an independent press.

Upon entering the exhibition, my attention was immediately drawn to books and other printed materials, including pamphlet collections, prominently displayed on the walls as (art) objects. We can appreciate their cover designs, often limited to the front cover or dust jacket and grasp their physical dimensions. As art objects, these books represent the intricate processes that led to their creation, and in consequence can be regarded as an individual art project, elucidated by accompanying wall texts and complemented by other objects such as prints and ephemera. This ‘objectification’ of books is underscored by the side-by-side presentation of two different editions of the same title—the softcover and hardcover versions, which accentuates the difference in physical attributes between these two renditions. However, while I wholeheartedly appreciate the gesture of elevating the book to the status of an art object, there was a certain unease in my experience of observing books displayed on the wall. Firstly, there was the curiosity about what lay within the pages of these books. Secondly, there was the longing to physically interact with them—to open the covers, peruse the pages, and explore the quality of the paper, its texture, smell, and weight.

The chronological journey through the gallery, providing visitors a historical trajectory of Something Else Press publications, concludes with a poignant exhibit. A cubic vitrine features a printed rendition of the Press’s epitaph, a card bearing the dates of its foundation and its subsequent closure, which was sent by Higgins to his friend and artist Sari Dienes in 1974. Near the vitrine the curatorial team assembled a collection of pin-back buttons, each bearing a motto hinting at the prospect of continuing the project: “If you can’t do it twice, you haven’t really done it.”

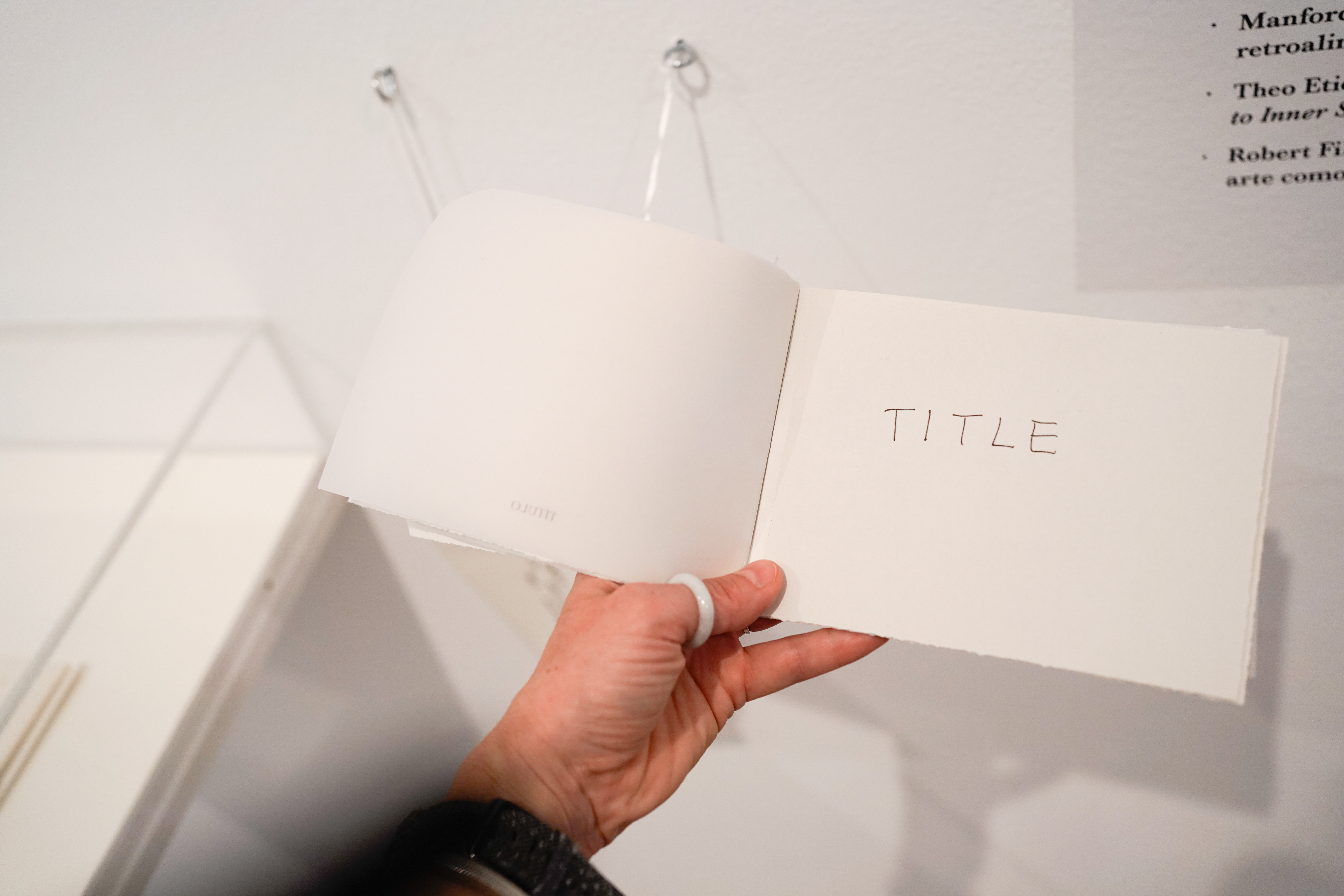

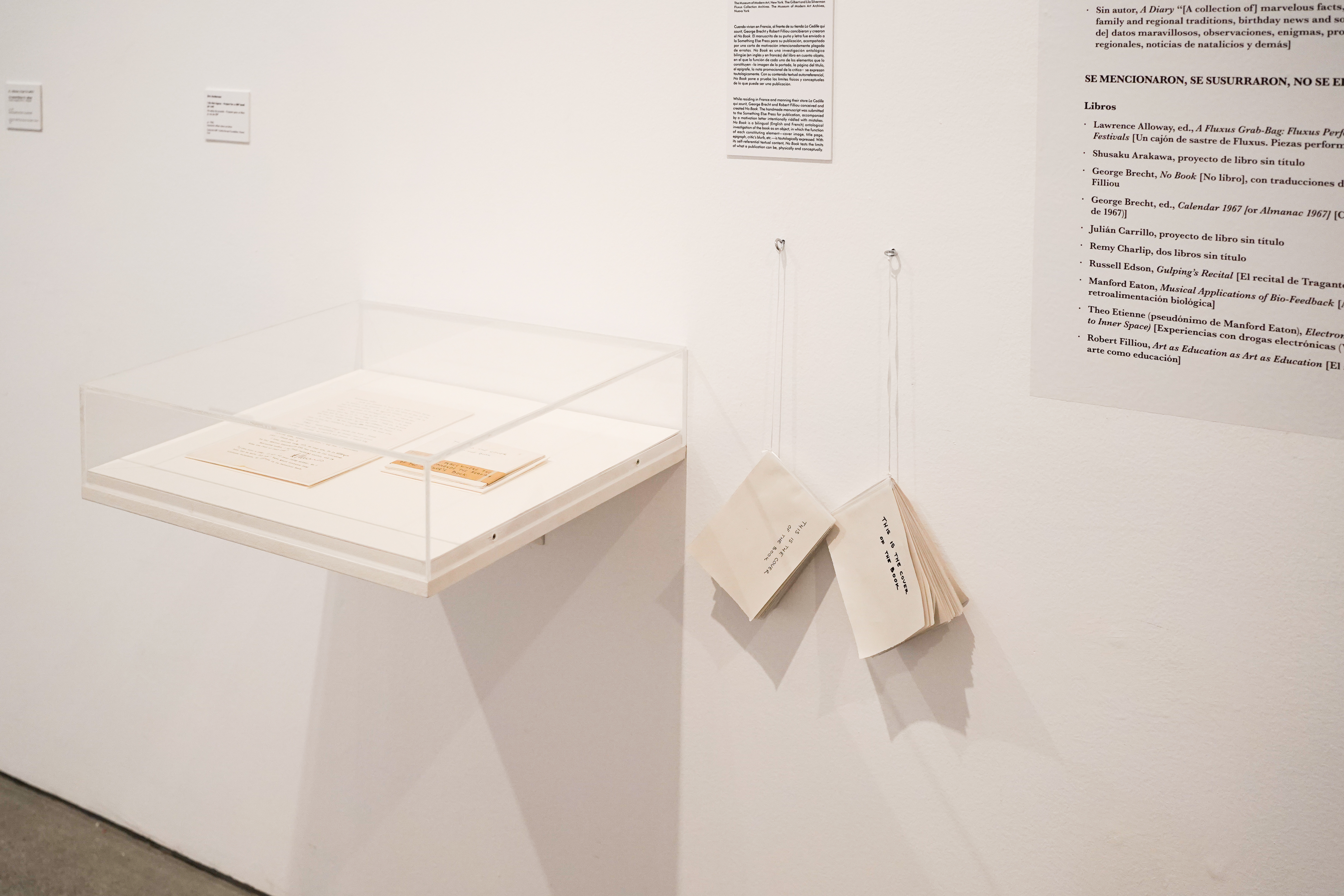

The intention to enhance the tactile experience with objects was introduced in the second room of the exhibition, specifically in the section displaying Something Else Press’s unrealized projects. One of the vitrines presents a remarkable artifact: the handmade ‘manuscript’ of Unpublished No Book (1965) by George Brecht and Robert Fillou, a gem from MoMA’s Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives. Unpublished No Book examines the book as an object, and the function of its constituting elements – cover image, title page, epigraph, and more. In order to enable exploration of this exceptional piece and ensure the accessibility of its content, the curatorial team decided to produce a facsimile that could be handled and consulted by the public. I took the opportunity to engage with it briefly, enjoying the chance to interact with its content and trying to compare it with the original version on display in the vitrine. Unfortunately, as I handled the delicate object, its pages began to come loose. I promptly reported this incident to the room’s attendant. In an unexpected turn of events, I found myself temporarily detained and prevented from leaving the space until the damage could be assessed by the gallery floor manager. I sat on a bench, feeling a mix of embarrassment and concern about the potential consequences. My time at the museum was limited, and I was eager not to miss any of it. As I waited for the situation to be clarified, I contemplated the ironic twist— the facsimile, designed to grant access to the book’s content, had inadvertently exposed its material fragility and the potential repercussions of its use. Moreover, the pleasure of delving deeper into the exhibit was dampened by the sense that this piece was originally designed rather for intimate appreciation not for a public scrutiny. It seemed as if the object itself resisted the curatorial attempts to make it more accessible to the public. I couldn’t help but feel like an unwelcome intruder. After a while, I was released without further charges, allowing me to continue my exploration of the exhibition.

In the same room, displayed in a playful dialogue with the presentation of Higgin’s Intermedia theory, is a project by Alison Knowles, Higgins’s artistic and life partner and a pivotal figure in Something Else Press’s history. The Big Book (1966), a monumental creation measuring one and a half meters in width and two and a half meters in height, featured eight movable pages on rails. This living structure was equipped with a kitchen, reading area, art gallery, bathroom, and sleeping tunnel and it was designed as an environment where each visitor, upon entering, became an active contributor to the content of every page. Initially, The Big Book was a special edition of one by Something Else Press, eventually evolving into the prototype for the unrealized Big Big Book, intended to be ten times its size. Regrettably, the original structure created by Knowles was gradually disassembled and no longer exists today. The exhibition offers a glimpse into this ambitious project by representing it through a life-sized photograph and a video featuring Higgins and Knowles interacting with the book’s pages.

The second section of the exhibition is devoted to the program of the Something Else Gallery, an extension of Something Else Press, that opened in Spring 1966 in the living room of Higgins’s and Knowles’s New York home. Its primary objective was to show works that transcended traditional media boundaries, defied conventional categorization and, as a result, would be deemed unsuitable for display in more traditional art spaces. In addition to its exhibition program, the Gallery served as a distribution point for the Press’s books, a venue for music concerts as well as a site for other initiatives, including workshops, book launches, and various less-categorizable endeavours like a continuous public reading of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. This section aims to immerse the viewer in the activities of the gallery by presenting photographic documentation of the exhibitions, snapshots from their openings, flyers, object checklists, and selected works that were featured during the shows.

& University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries.

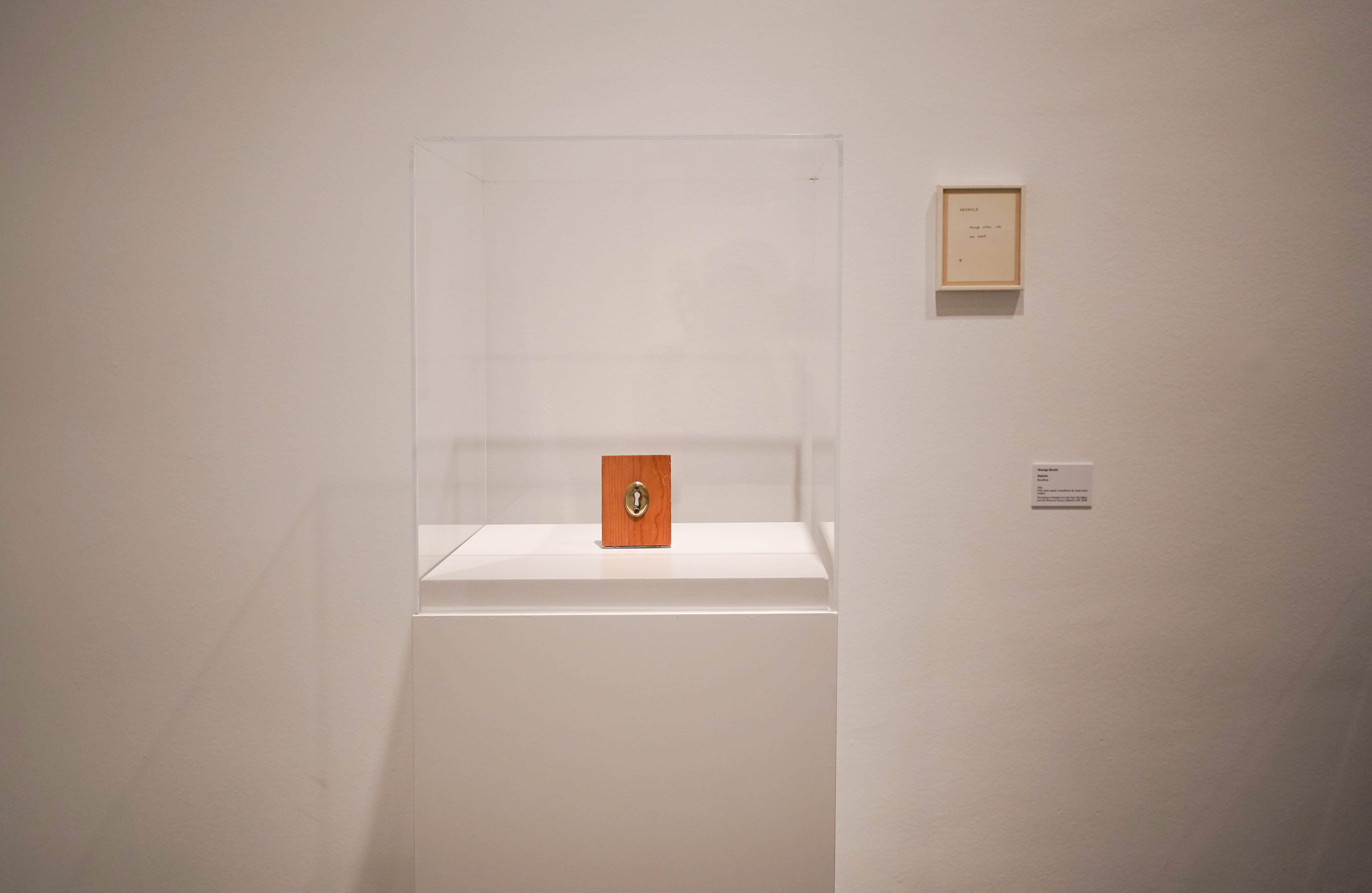

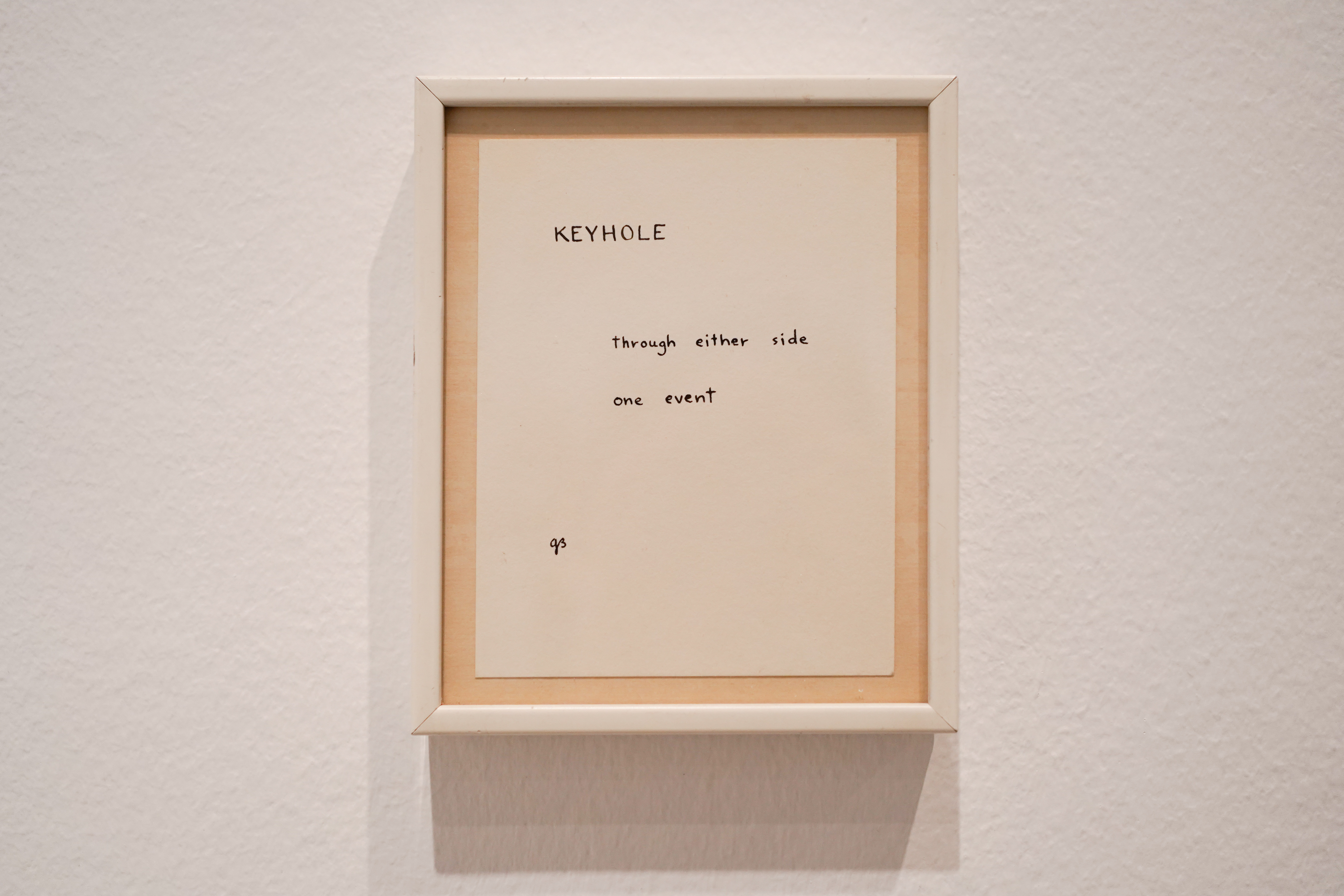

In this section objects fulfil their expected role, namely as art objects to be appreciated in their own right. The three rooms, full of vitrines, illustrate a common challenge faced in exhibitions featuring art created within the Fluxus circles—the limitation imposed by museum settings on interacting with objects that were, from the outset, intended for physical engagement. For instance, consider George Brecht’s Keyhole (1962), comprised of an event score reading “through either side one event” and an actual keyhole protected with a glass enclosure, with its back side facing the wall and being hardly accessible. This issue is also exemplified by the Finger Box Kit (1965) conceived by Ay-O and designed by George Maciunas, consisting of 15 tactile boxes intended to be experienced by inserting a finger into a hole, thus evoking surprise through the tactile sensations of their contents.

and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, 2008

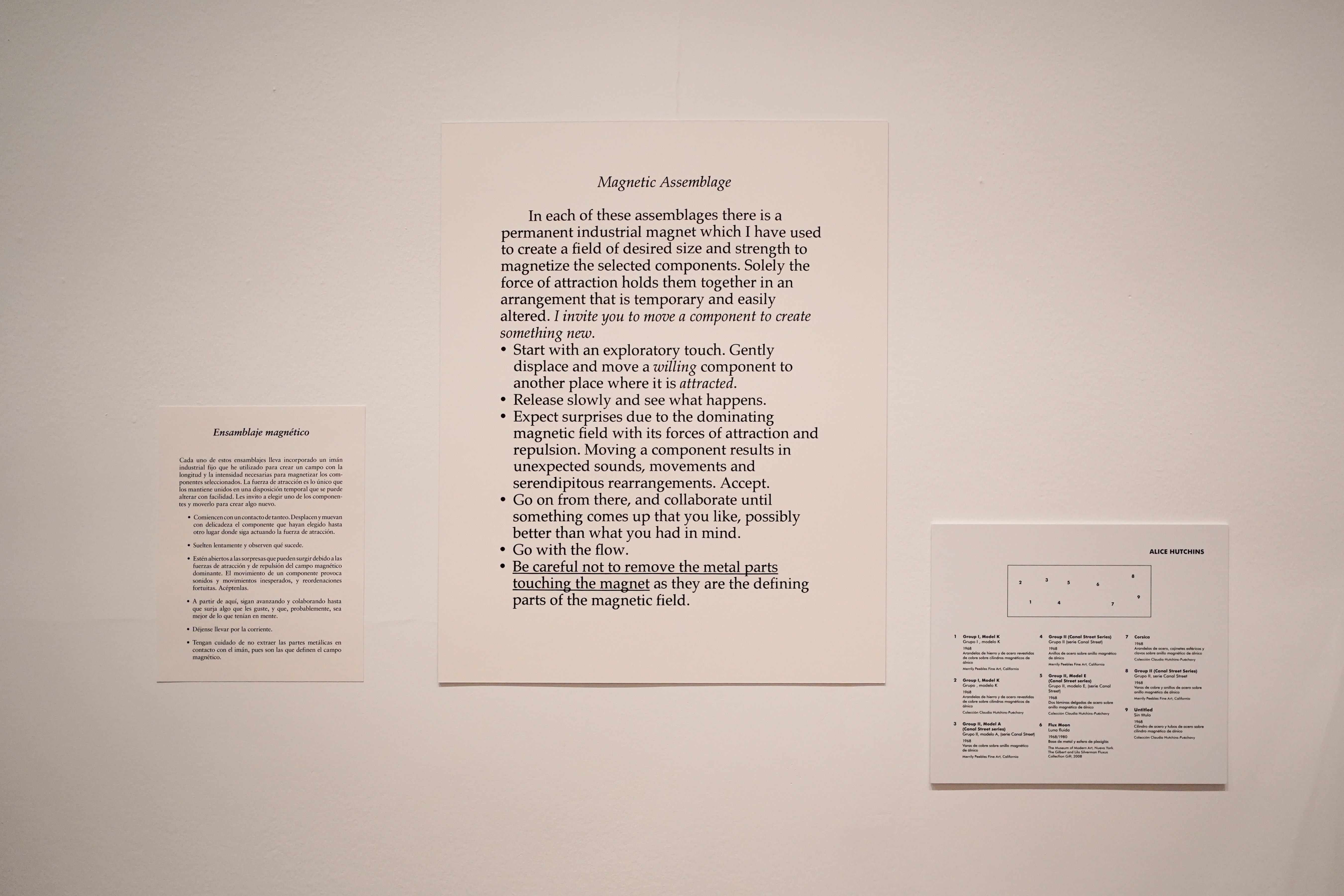

The section ends in a room dedicated to Alice Hutchins and her 1968 exhibition titled “Quelques-choses de magnétiques! (Some Magnetic Things!).” As the title suggests, the objects in this exhibition are structures crafted from magnetic elements. Hutchins transformed the Something Else Gallery into an interactive and collaborative playground, inviting the public to partake in the creative process and to activate the movable magnetic components of her constructions. This playful engagement is conveyed through photographic documentation. During my visit to the gallery, where the objects were either enclosed in vitrines or placed out of reach, I observed another interesting interaction with the room attendant, this time, thankfully not directly involving me. On one of the walls, the curatorial team displayed a reprint of instructions written by Hutchins on how to interact with the objects during the 1968 show. After reading these instructions and understanding that they pertain to the current exhibition, a young couple approached the attendant with a query about why the objects apparently intended for manipulation are not accessible to the viewers. Recalling my recent experience of handling a delicate exhibit myself, I couldn’t help but wonder what the public could discover about and learned from Alice Hutchins’s objects if given the opportunity to engage with them as freely as the visitors to the show at Something Else Gallery did in 1968.

The variety of practices that received support during the eleven-year existence of Higgins’s project are exemplified in the third section of the show. This section is further organised into projects, most of which are linked to specific Something Else Press publishing endeavours. One notable example is Notations (New York, 1969), the collection of music manuscripts assembled by John Cage to be exhibited in a benefit show aimed at raising funds to support performing artists. Unfortunately, Cage encountered difficulties in finding a suitable venue interested in hosting the show, ultimately resulting in the catalogue, co-edited with Alison Knowles and published by Something Else Press, becoming an archive of an unrealized project. The selection of notations from Cage’s collection that are displayed in the show try to convey the rich diversity of their forms and contents.

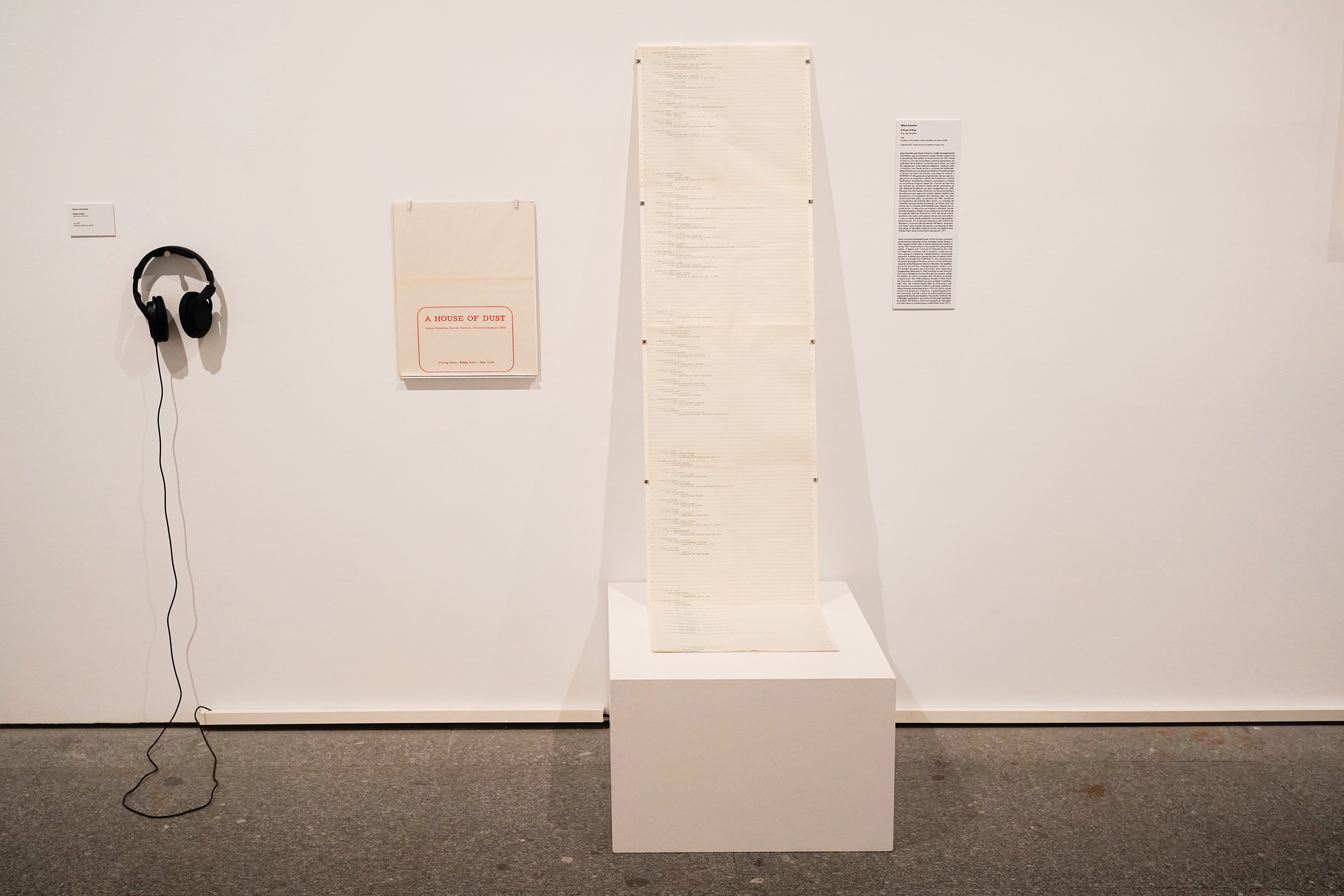

Knowles continues to have a significant presence in this section trough two of her projects. The first one is the “T” Dictionary, published by Something Else Press in the volume The Four Suits (New York, 1965) and rearranged into a new, wall version by the artist specifically for this exhibition. The second one, the House of Dust, started during a computer programming workshop at the Something Else Gallery in spring 1967 as one of the first computerized poems, written in Fortran code, with randomly assembled verses. Each quatrain began with “A house of …” followed by sequences of materials, sites or locations, light sources, and categories of inhabitants randomly matched by a computer program. Later, one of the the quatrains became the score for The House of Dust public sculpture, installed at a New York housing development in 1969. The next year, Knowles moved the sculpture to California Institute of the Arts, where it became a space for teaching and a site for activations by students. The project is represented in the show through the 1969 edition published by Verlag König in Cologne and a set of photographs showing the activities that unfolded around the California iteration of the project.

The portrayal of the tangled network involving intermedia artists and art projects often indirectly associated with the Press extends beyond the boundaries of the gallery spaces. In a corner of the Museum corridor, nestled between different sections, visitors will come across an enigmatic installation: a circle of 12 empty bottles arranged on the floor. This space serves as a reenactment site for a historical performance by Fluxus artists Thomas Smith, proposed by artist/curator Christian Xatrec and interpreted by choreographer and dancer Tatiana Arias. Zyklus for Water-Pails (or Bottles) (1962), while only activated occasionally throughout the duration of the exhibition, represent the medium of live art that played an important role in the development of artistic practices of that time and context and that is showcased in the exhibition rooms only through the documentation. While watching the performer slowly poring the water from one bottle to the next, I couldn’t help but envisioning my own attempt to interpret Smith’s piece within this setting. In the following moments, my museum background prompted me to mentally compile a hypothetical list of potential consequences if the public were permitted to independently activate the performance props. It quickly became evident that such an endeavour would be fraught with challenges, bordering on the near-impossible.

This brief exploration of the exhibition aims to illustrate the curatorial team’s playful and mindful approach to showcasing a complex and historically significant art project. My main takeaway is that, despite having been mainly associated with its leader, the Press developed often organically from a diverse array of autonomous artistic endeavors, all of which were influenced and shaped by a multitude of collaborations, associations, alliances, and conflicts. While the exhibition builds on historical facts such as dates and names, nothing else is set in stone. The show thrives on a fluid, indirect and often convoluted web of references, which, rather than detracting from the experience, adds an element of mystery, making it even more intriguing. Visitors are invited to immerse themselves in a distinct universe, one that organically evolved around Something Else Press and which is populated by individuals whose personalities and artistic interests become known to us through their creative practices showcased by their own works

Interestingly, the exhibition places the charismatic founder of the Press, its mastermind, and driving force, Dick Higgins, somewhat in the background. Here, Higgins is portrayed more as a facilitator and supporter—providing spaces for artists to present their work and proposing theoretical frameworks that underpin their contributions. Even his own art, in the more traditional sense of the word, that is beyond books and publishing projects, is showcased outside of the main galleries in a projection corner dedicated to his films. Although I deliberately highlighted the presence of Alison Knowles in the exhibition, I did so because her involvement in Something Else Press activities appears to resonate as strongly, if not more strongly, than that of her partner. This choice, perhaps intentional on the part of the curatorial team, is even reflected in the title of the exhibition itself. Ultimately, it was Knowles who suggested that Higgins should call the press “something else”.

The art practiced within the Something Else Press community often defied the creation of discrete, easily exhibitable art objects, which could be solely appreciated through visual means. In fact, this art frequently challenged the status of objects, including the objectification of the creative process and the the rise of art as a commodity. Nonetheless, to create an exhibition within a visual art context, it becomes necessary to present objects, and the curators of the show have successfully employed various methods to address this need. Understandably, the objects featured in this exhibition serve less to directly showcase the art created by particular artists and more to represent the type of art that was disseminated trough Something Else Press and presented at the Something Else Gallery. However, I couldn’t shake the feeling that here, objects and artworks (as in the case of Finger Box Kit orZykulus) inadvertently manifest, at least to my perspective, the inherent constraints of the museum exhibition format and the perennial struggle between providing access to contemporary art and safeguarding its artifacts and the inherent difficulty of the current museum setting to allow artworks to simply be their authentic selves. As Higgins stated in his Something Else Manifesto, we might gain a deeper understanding of an idea once “a little soup has been spilled on it”. Certain art objects might require a degree of physical engagement and disruption to be fully and genuinely appreciated.

Factual details presented in this text are sourced from the wall labels and curatorial texts provided in the context of the exhibition “Call It Something Else: Something Else Press, Inc. (1963-1974)” at the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid (September 27, 2023 – January 22, 2024).

Featured photo: Dick Higgins’s Jefferson’s Birthday/Postface (New York, 1964). Installation view of the exhibition “Call It Something Else: Something Else Press, Inc. (1963-1974)” at the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid (September 27, 2023, to January 22, 2024). All photographs: Aga Wielocha / Activating Fluxus.