The Chase-Manhattan bank scheme landed me in jail for a short while, since I was able to escape by tunneling out through various cellars into a loft building on Canal street. I cut through the floor andended [sic] up inside Ayo’s tactile hand box. I did not realize at first what it was until I saw a hand enter a hole at top of the box and stick a finger into my mouth. Then I heard Ayo say that the box had a mouse but he did not realize it could grow so much so quickly.

George Maciunas, Dec. 10, 1975[1]

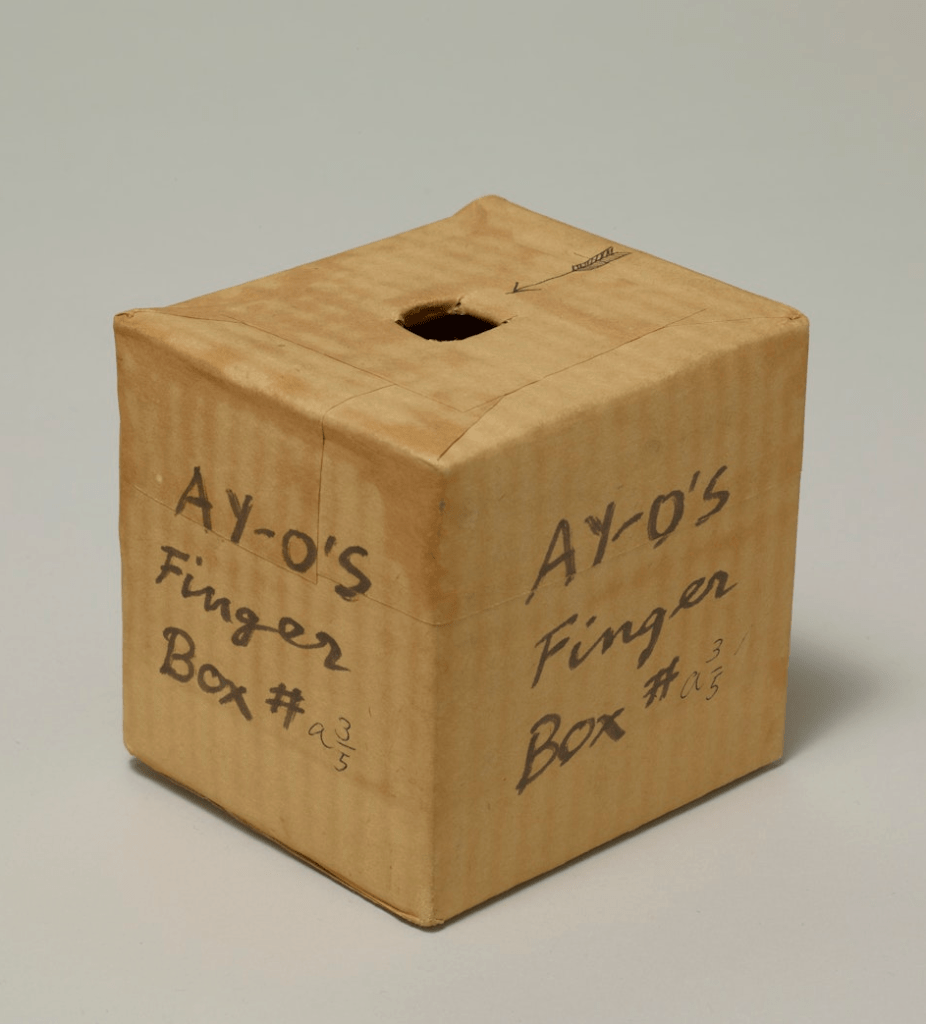

Perhaps no other Fluxus works demonstrate as powerfully as Ay-O’s Finger Boxes (1964-ongoing) how fundamentally Fluxus forms reject the foundational logic of art museums – that art’s value resides in unique physical objects created by individual authors, which institutions must preserve and protect. Born out of artistic exploration of touch, these finger boxes in museum collections and displays – whether stored or exhibited – are often stripped of their primary function: to provide the possibility of experiencing the unexpected but unseen through tactile engagement by simply sticking a finger into a little hole in the box. What might this experience be like? Materials like rubber, nails, vaseline, silk, velvet, sand, and feathers generate touch sensations such as warmth, sliminess, softness, sharpness, hardness, stickiness, and smoothness that in turn produce feelings of revulsion, pain, discomfort, surprise, and pleasure. In most cases, these boxes are fragile, made from precarious materials that are now more than half a century old and partially disintegrated, rendering them off-limits to the public touch with museums citing conservation concerns as the reason. The haptic experience is reserved only for privileged museum professionals and selected members of the public, such as researchers. Even then, the interaction becomes a carefully monitored exception rather than the playful, experimental exploration of careful touch, that Hannah Higgins drawing on David Michael Levin’s words, described as “an enquiring, learning gesture.”[2]

The tension between the interactive and participatory intent of these tactile devices and their current prevailing presentation in museums raises questions about the predominance of material preservation over public access. Whether displayed behind glass, positioned out of reach, or represented in online catalogs through photographs and brief descriptions that often fail to specify the source of tactile experience, Ay-O’s tactile devices challenge museums to balance two competing imperatives: providing access to art designed to be experienced through touch rather than merely viewed, while simultaneously protecting material integrity when necessary. Rather than attempting to resolve this tension, in this post I examine the history and context of these works’ development to better understand the workings and affordances of their interactive and participatory character.

However, the central challenge that Ay-O’s tactile devices present to museums – and that museums present to these works – will be explored by curators and conservators at The (Im)possibilities of Touch: Ay-O’s Finger Boxes – A Conservation Study Day. Organized by Activating Fluxus in collaboration with the Getty Research Institute on February 26, 2026, this event will bring together museum professionals to address these tensions directly. A second post recapping their discussion will follow shortly after the event, so stay tuned.

Ay-O was born on May 19, 1931, in Namegata City, Ibaraki prefecture, Japan. After graduating from the Art Department of the Tokyo University of Education in 1954, he worked as a junior high school teacher while beginning his artistic practice with the Demokurato Artists Association, an alliance of graphic designers, photographers, performers, painters, and writers that promoted artistic freedom and independence outside traditional hierarchies through group exhibitions and a self-published magazine. On his twenty-seventh birthday in 1958, Ay-O departed Japan for New York, drawn by a desire to explore international approaches to art-making.[3] Through the vibrant circle of Japanese and Japanese American artists he encountered there, he met Yoko Ono, who between 1961 and 1962 introduced him to George Maciunas and the wider Fluxus network.

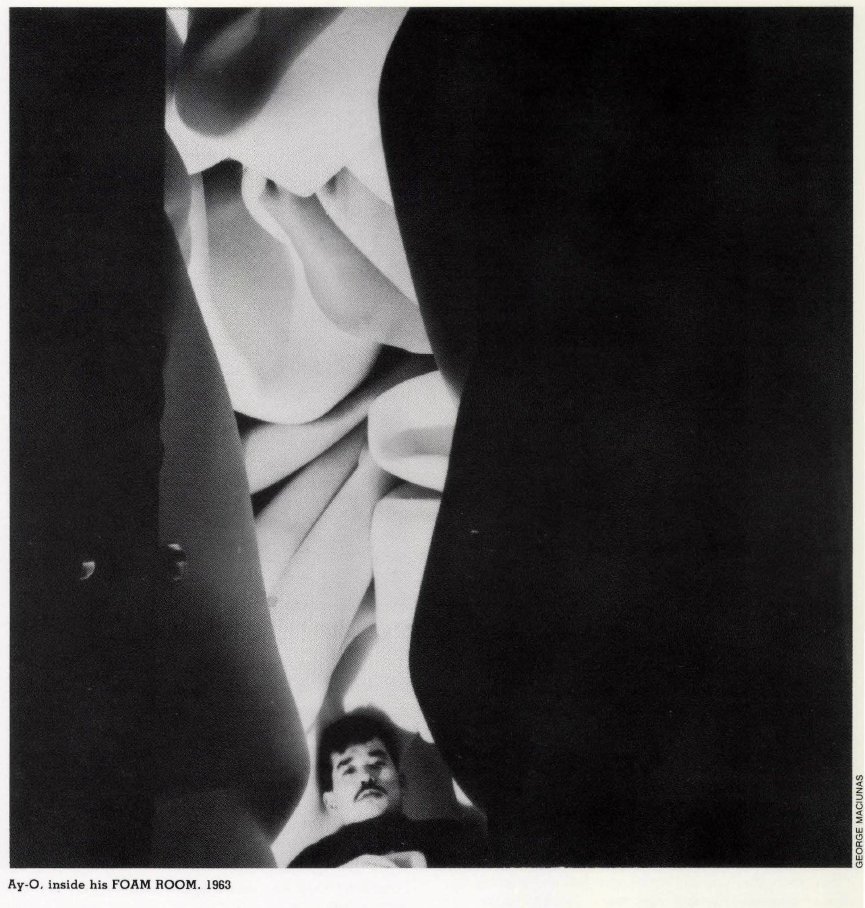

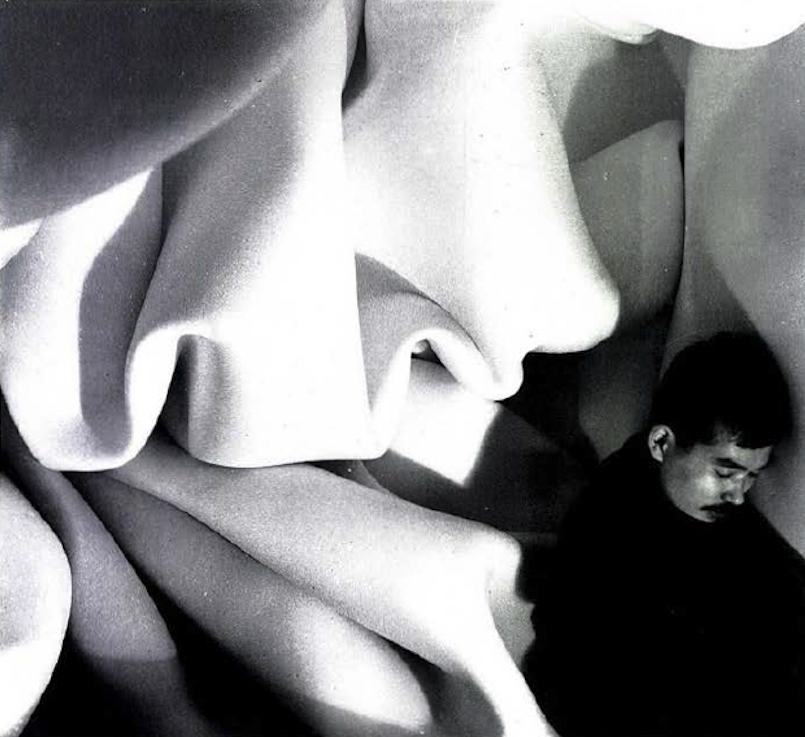

According to Ay-O, his adventure with exploration of touch started in the fall of 1962 following a solo exhibition at Gordon’s Fifth Avenue Gallery in New York. A visitor approached him with an offer of large amounts of rubber foam for free. As Ay-O recalls, “the studio was filled to the brim with rubber foam, and I could not even move […]. From the following day, I immediately started grappling and having a dialogue with the rubber foam.” [4]

In essays originally published in 1986–1987 and later translated into English by Midori Yoshimoto,[5] Ay-O described his progression toward tactile devices:

I had broken free of the New York School and subsequently all preexisting art, searching for a work that would be completely new and solely my own, based on my senses and composed of concrete things around me. […] So then I told myself that it was my duty to ascertain how all the materials around me affected my six senses. As a method of testing this, I haphazardly tested whatever concrete objects I could get my hands on in whatever way I could think of.[6]

He elaborated on the properties of rubber foam:

Rubber foam is completely white at first, but it ages into a sexy yellowish tone and finally turns a dirty brown color evoking a feeling of the end. The shapes that can be made from it are spongy, indescribably erotic, and unique. Using these properties, I created various works, but above all else, I felt that what stood out was the unique, soft, and warm feel to the touch. Thereupon, I decided I would use this opportunity to examine every aspect regarding the sense of touch.

pen, and ballpoint pen, containing foam rubber; The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift,

source: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/131474 and Ay-O, Prototype for Fingerbox (1964), edition 3/5, cardboard, foam, ink, paper, Walker Special Purchase Fund, 1989; source: https://walkerart.org/collections/artworks/fingerbox

The experience with rubber foam led to the design of the first Finger Box. Ay-O recalls:

First of all, in order to make people pay attention to the sense of touch, I felt I needed to eliminate the sense of sight. If people could see, they tended to forget about their sense of touch. By seeing, people tended to compensate their sense of touch with their memory rather than actively touching. The sense of touch against the skin would not be generated unless the person or the object moved. I made my first Finger Box by cutting a cardboard box into a cube ten centimeters. I only needed a little bit of rubber foam to place in the center. I opened a hole that was about twenty-five millimetres in diameter, where people would stick in their finger and feel what was inside. I made a slit in a piece of high-quality rubber and placed it over the hole from the inside so that no one could peek into the hole.[7]

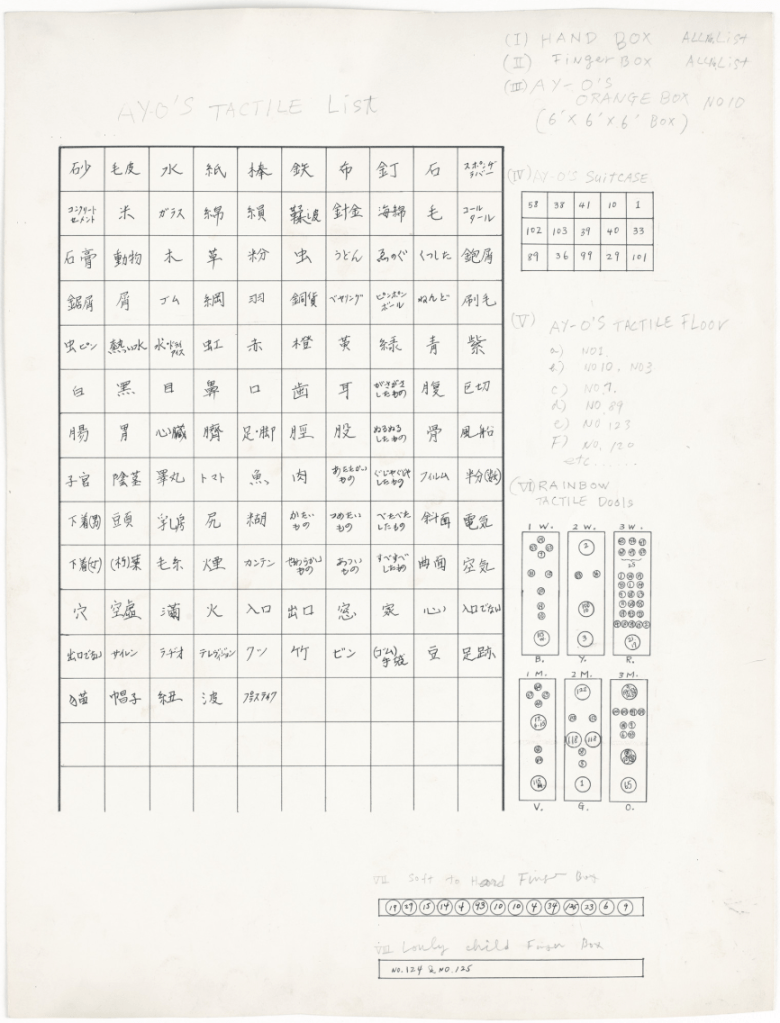

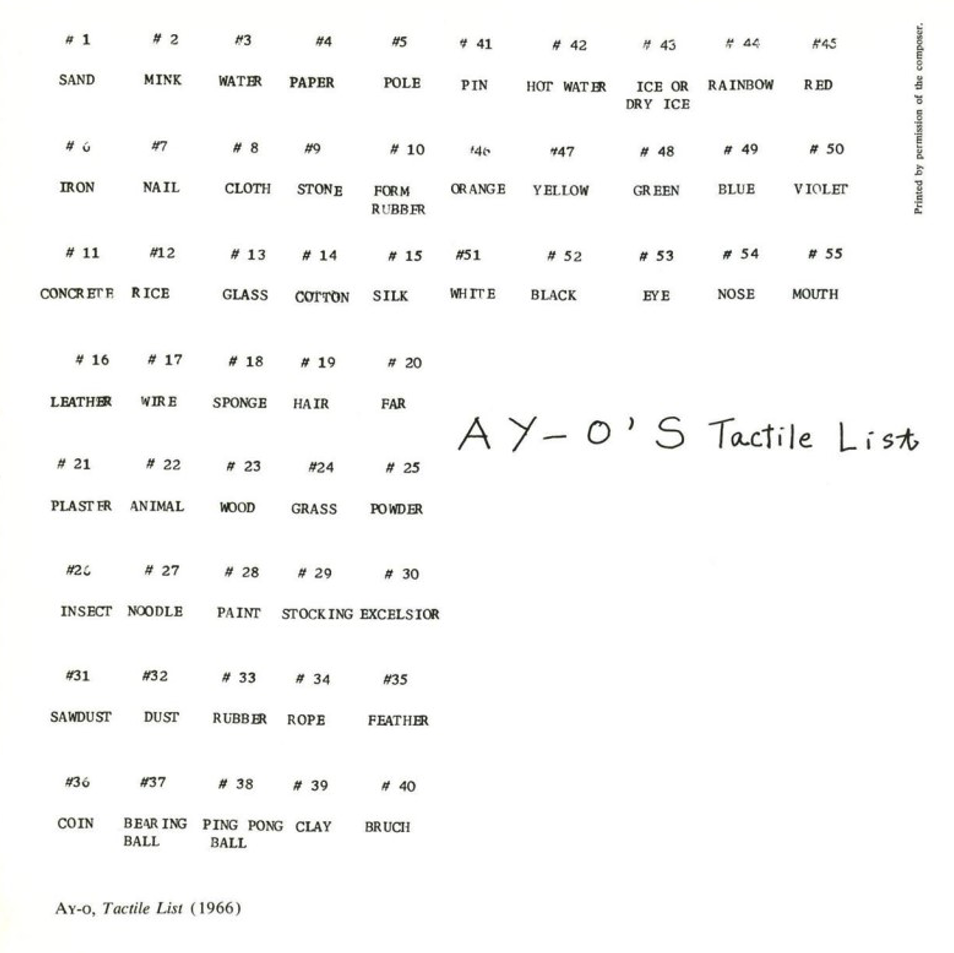

Concurrently with developing his first tactile devices, Ay-O created what he titled a Tactile List [Fig. 2]. He explained its genesis:

I am sure everyone was just as touched by the beauty of chemistry that I felt when I learned about the periodic table of elements in my middle school physics class. […] I wondered if it was possible to make a similar “list of tactile sensations” and then I became immersed in collecting tactile objects. It has been thirty years since then, but still I am not sure what to do. So, I still have today just a list of examples simply lined up.[8]

source: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/131574

The English version of the “Tactile List” reveals that some tactile sensations are not straightforward and require considerable imagination and specific previous tactile experiences for interpretation. Fragments of this list were later published in John Cage’s Notations, suggesting the list could be considered a score for future works [Fig 3].

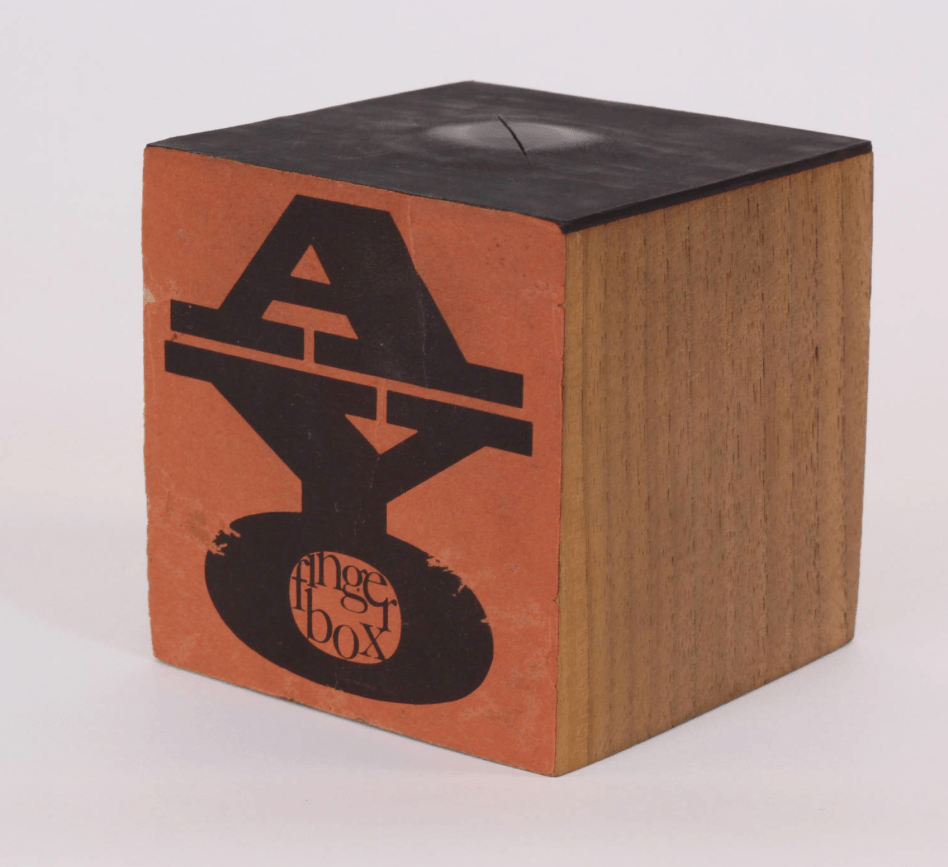

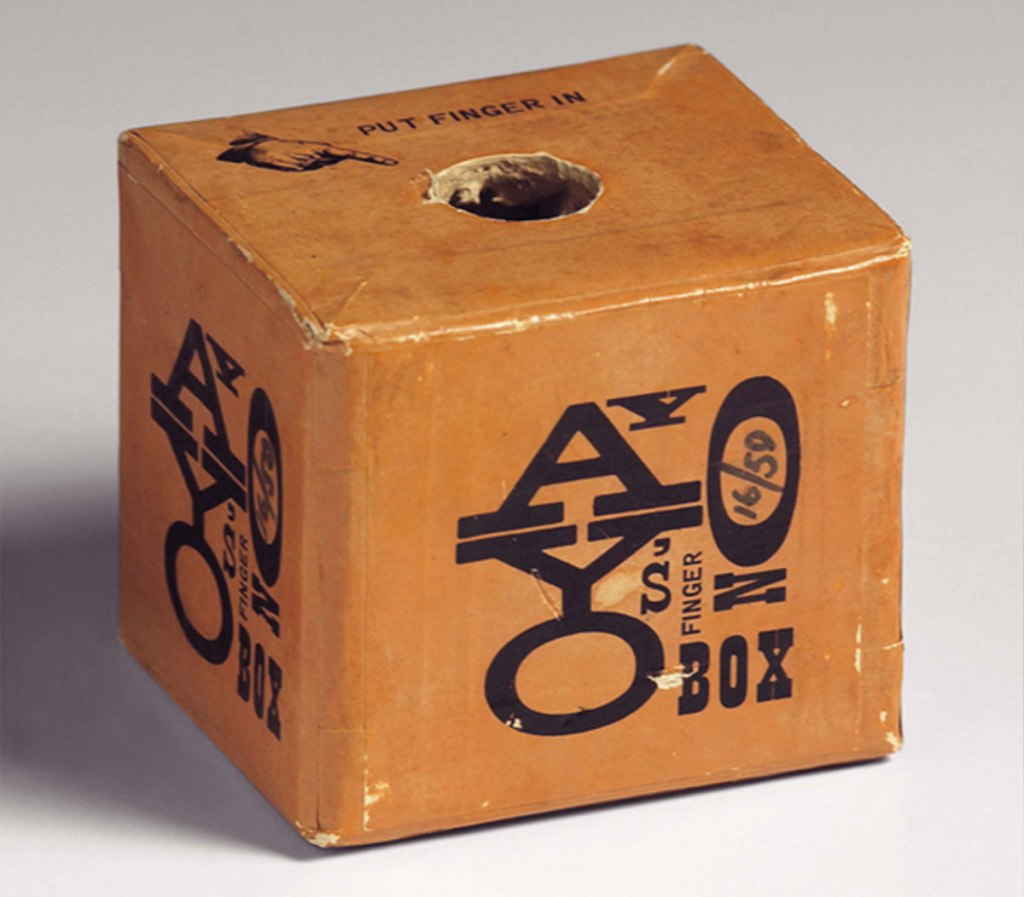

At some point, the Finger Boxes and other tactile devices acquired Maciunas’ distinctive design aesthetic and the “Fluxus branding.” Although Maciunas was involved in producing Ay-O’s tactile devices throughout the years, Ay-O recalls that adopting the Fluxus look was his own decision: “Around the outside of my Finger Box, I pasted orange paper and printed the ‘AY-O’ monogram designed by George.”[9]

Finger boxes were not Ay-O’s only tactile devices. His experimentation with touch led to designs engaging other body parts or even the entire body in tactile immersion:

In the beginning, I always tried to create an artwork as if it were a very small diamond, retaining its complete essence within itself, but in a split second the artwork expands. After Finger Box, I made a thirty centimeter cubed Arm Box, into which one would insert their whole arm.[10]

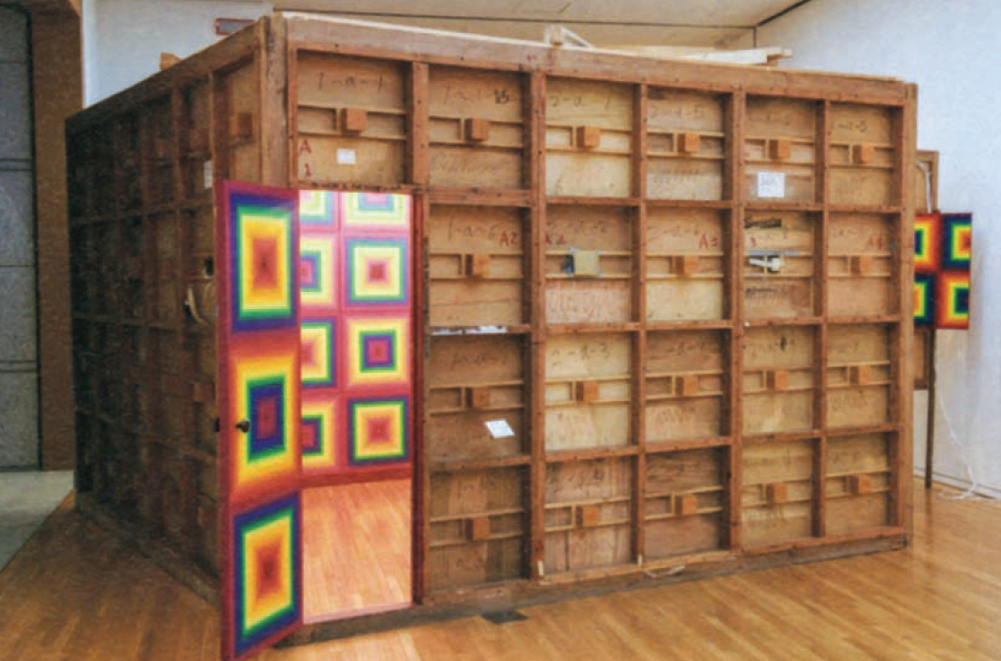

He continued, “Subsequently, I was driven by the desire to make a piece that could fit an entire body.” This led to the creation of the Orange Box – also known as the Body Box or Foam Room[11] – a 1.8-meter cube filled with industrial-grade foam that invited full-body tactile immersion, that subsequently acquired the subtitle Tactile Environment.[12] The Orange Box gained significant attention when Ay-O appeared with it in 1964 alongside Yoko Ono on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson in an episode featuring Paul Newman.[13] This emblematic work met its end on February 20, 1979, when it was burned as part of a memorial for George Maciunas.[14]

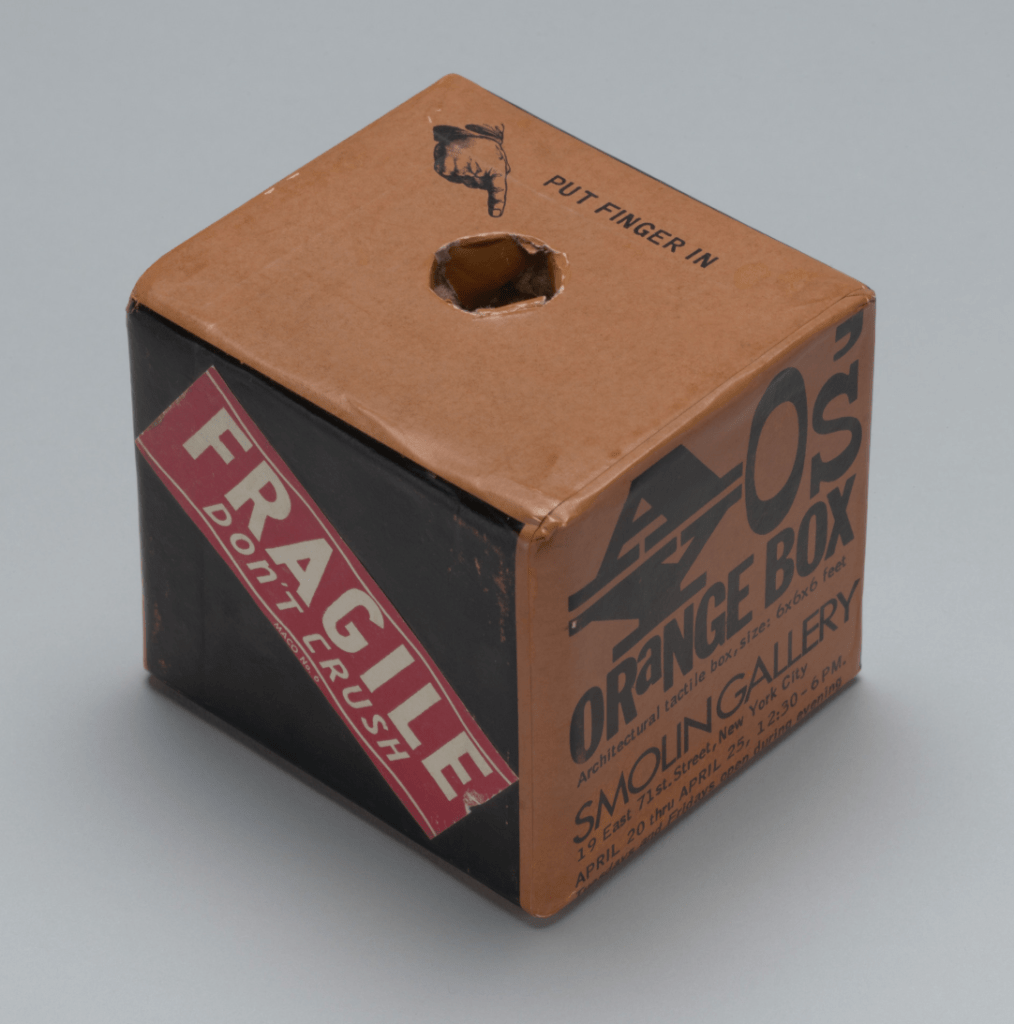

The Orange Box was displayed in 1964 at an exhibition hosted by the Smolin Gallery in New York. For this occasion, Ay-O (and, judging from the box design, probably Maciunas, though Ay-O’s writings do not mention his involvement directly) produced a Finger Box that served as an invitation to the show [Fig 6]. Ay-O recalls:

Four or five of my friends helped me produce approximately eight hundred of the boxes in an organized fashion. Anyway, there was a mountain of foam rubber to use. Printed on the top of the box was a pointed finger stating “Put Finger In.” It was designed so that when one pushed down, the top layer of paper would rip, and the finger would go inside the box. On one side, I used a prefabricated red ‘fragile’ label against a black background.”[15]

He added, “On the other two sides, I put advertisements for Finger/Tactile (Arm) Box and the Fluxus Shop. And, on the last side, I placed the announcement for the Orange Box exhibition. Later one of my friends informed me that most of the Finger Boxes were no longer ‘virgins,’ because the mailmen would stick their fingers in them before they arrived at their final destinations.”[16]

Fig 6. Ay-O, Finger Box (1964) that served as an invitation to the show at Smolin Gallery. First image – an edition from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, source: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/128028 and on the second image an edition form IMMA Collection: Donation, Novak/O’Doherty Collection, 2015; source: https://imma.ie/collection/finger-box/

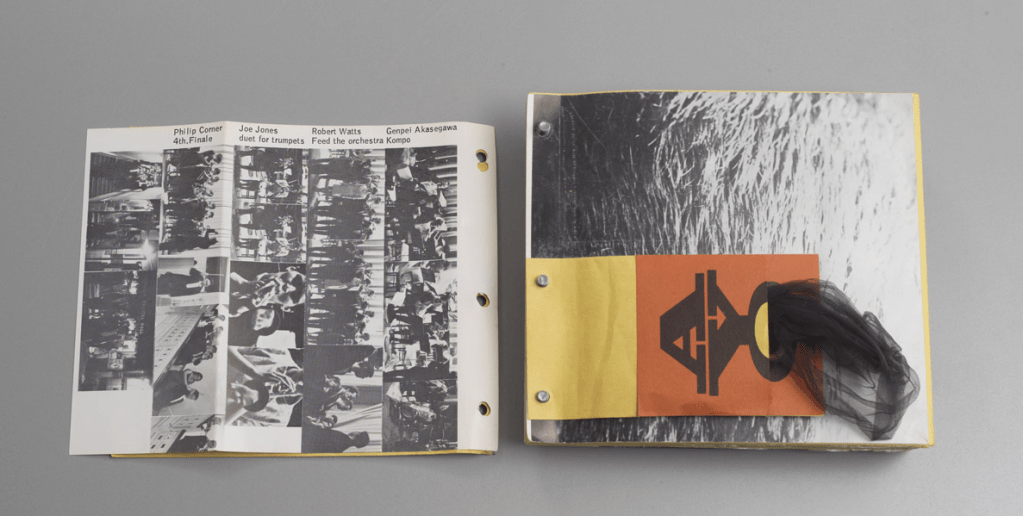

In 1964, a Finger Envelope –a flat, two-dimensional version of the Finger Box – was published by Maciunas in the Fluxyearbox [Fig 7]. The envelope’s contents remain uncertain: it may have contained only a piece of nylon stocking, or the stocking may have held additional materials that likely varied across different versions. The wooden Finger Box was included in other Fluxus publications, such as the Fluxkit, where the same model could function both as part of the Kit and as a standalone work [Fig 8]. In 1965, Maciunas elevated the Finger Box concept by producing the Finger Box-Kit – a briefcase containing fifteen wooden Finger Boxes with different contents [Fig 9].

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/126323 and Ay-O, Finger Box (c. 1964), University of Iowa Library / Special Collections, source: http://fluxus.lib.uiowa.edu/content/finger-box-0.html#images

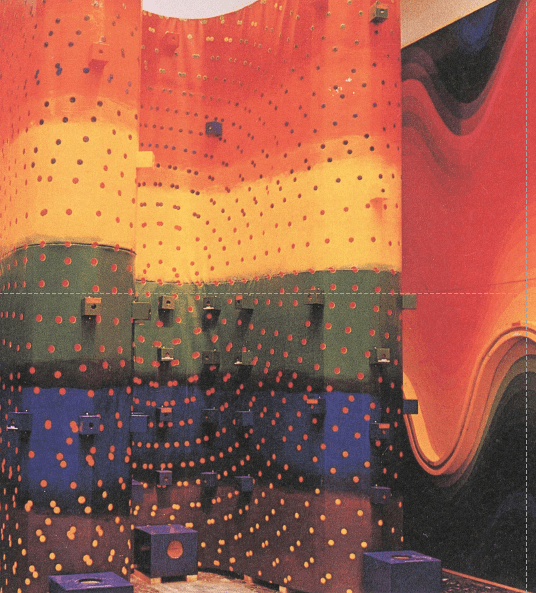

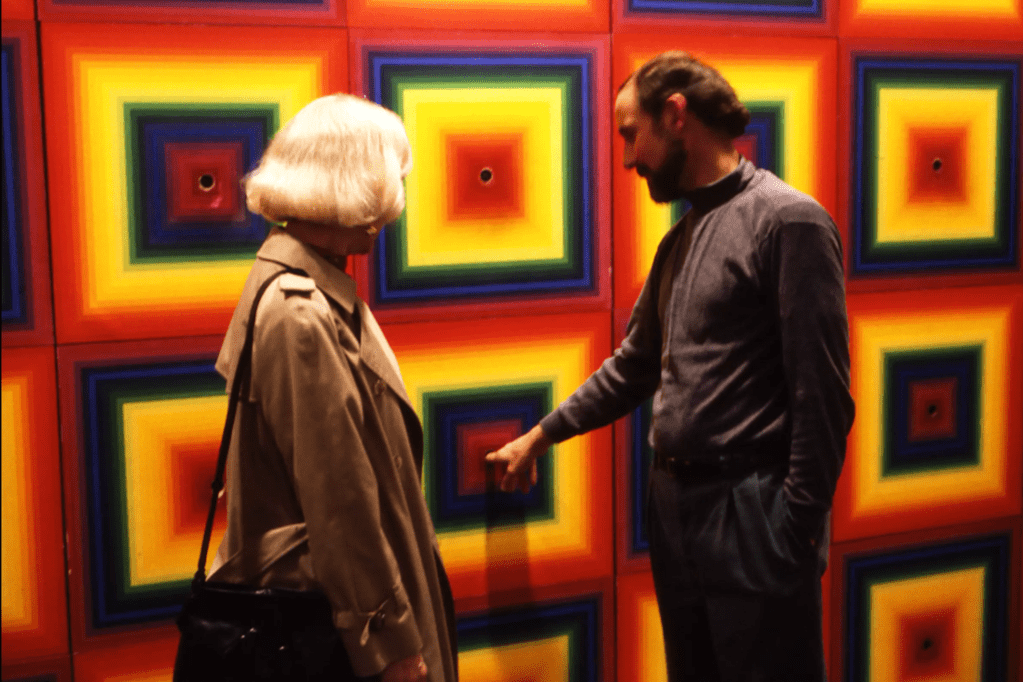

Although their pocket-size scale and designed use—one finger at a time—suggest an intimate, one-to-one interaction, Finger Boxes were nonetheless made available for broad public engagement. In 1966, Ay-O’s work was exhibited in the Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. For this occasion, he produced the installation Rainbow Environment No. 3: Tactile Room in Venice, which playfully combined two strands of his artistic practice—fascination with rainbow colors and touch. The Asahi Shimbun newspaper described Ay-O’s installation as “the largest-scale and most ambitious work” from any nation at the event:

[…] On the first undulating wall, there were sixty-five small tactile boxes called Finger Boxes, which had a label reading, “Audience, please place finger here.” When one placed his finger into one of the boxes, a radio would start playing or bells would ring. And, at the foot of this large canvas wall, there was a wooden box which had a label reading, ‘Place hand in here.’ When someone became intrigued and placed his hand inside, he would have been met with cold water. He would scream and swiftly retract his hand.[17]

The art magazine Bijutsu Techo reported that a German visitor allegedly suffered a finger injury from a thumbtack inside one of the sixty-five boxes and sued the commission—an incident that undoubtedly contributed to extensive press coverage of the show.[18]

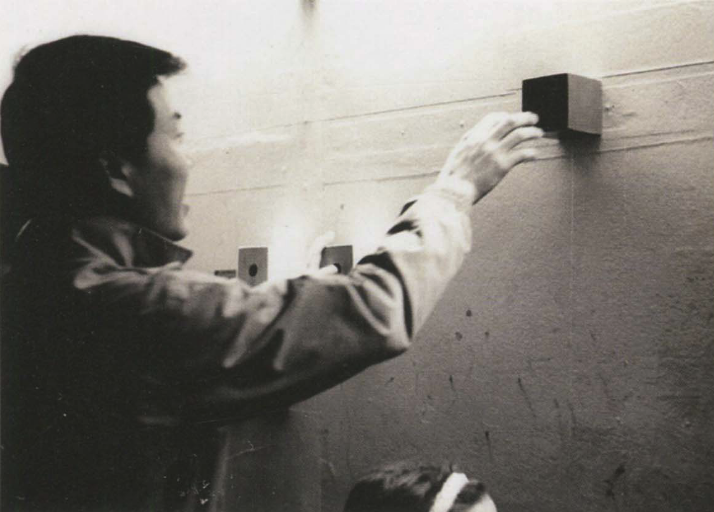

Later that year, Ay-O returned to Japan and played a central role in the landmark exhibition From Space to Environment, held at the Matsuya Department Store Gallery in Tokyo’s Ginza business district. The boxes were once again mounted on the wall for public interaction [Fig 11]. As Yoshimoto observed, several of the Finger Boxes were intentionally left empty, prompting “an unexpected recognition of the void” among participants.[19]

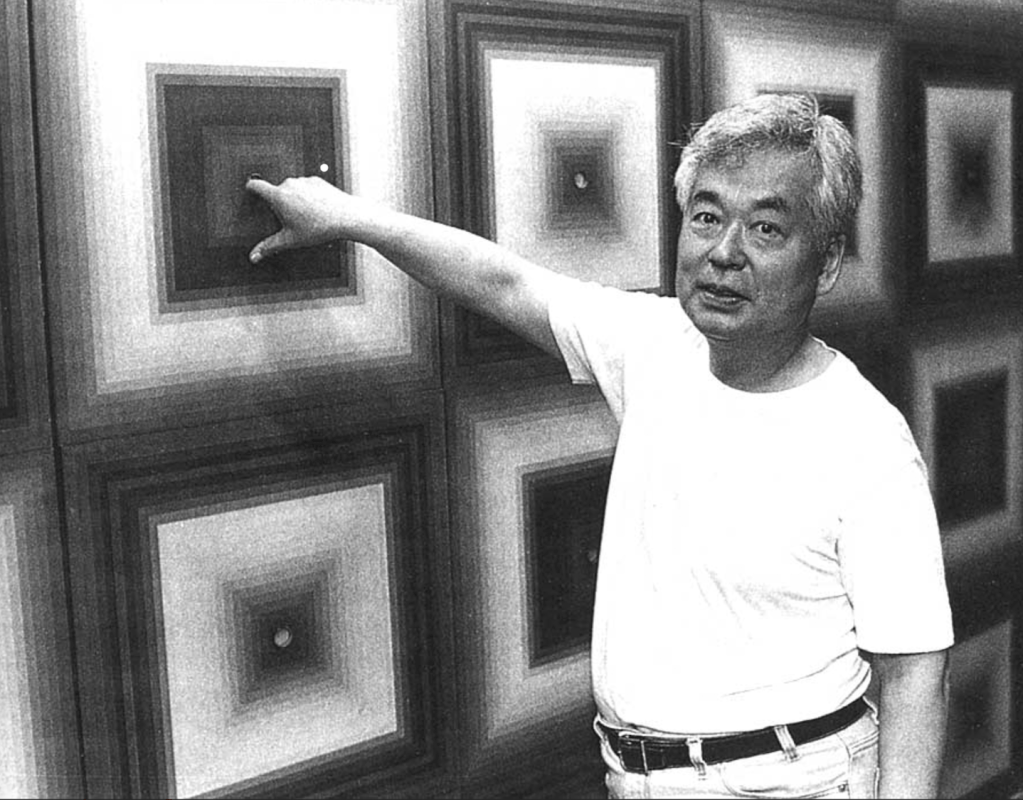

Another Rainbow Environment with tactile interaction is number seven, dated 1969 and subtitled Tactile Rainbow Room. This work, in contrast to the earlier site-specific pieces, has been exhibited on numerous occasions, including the 1990 exhibition Ubi Fluxus Ibi Motus in Venice and the landmark 1993 show In the Spirit of Fluxus at the MCA Chicago.

Source: Brooks, Kit. Ay-O Happy Rainbow Hell. Smithsonian Books, 2023 / Ay-O and his Rainbow Environment No. 7, photograph: Wolfgang Träger, “Klassentreffen. Wolfgang Träger fotografierte Fluxuskünstler beim Aufbau und bei Performances in Venedig und in Wien.” Kunstforum International, 1991. / Installation view, In The Spirit of Fluxus, MCA Chicago © MCA Chicago, source: https://mcachicago.org/exhibitions/1993/in-the-spirit-of-fluxus

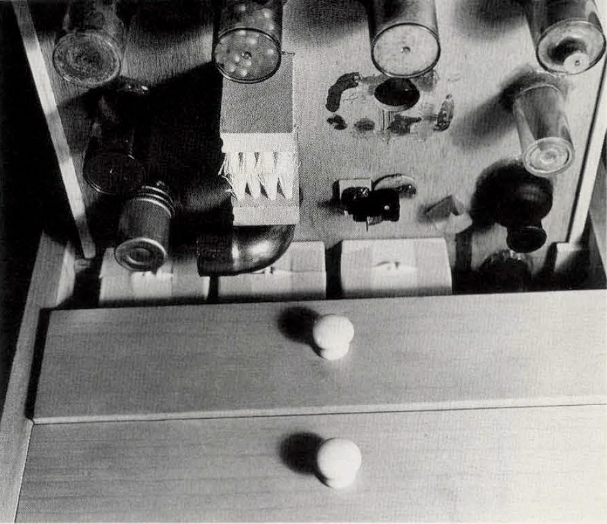

In the 1970s, Ay-O’s concept and design for Finger Boxes was adapted by Maciunas for his emblematic Flux Cabinet, designed for Susan Reinhold and currently held in The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection at MoMA. This piece, often referred to as the ultimate Fluxus anthology, includes one drawer representing Ay-O’s tactile experiments.

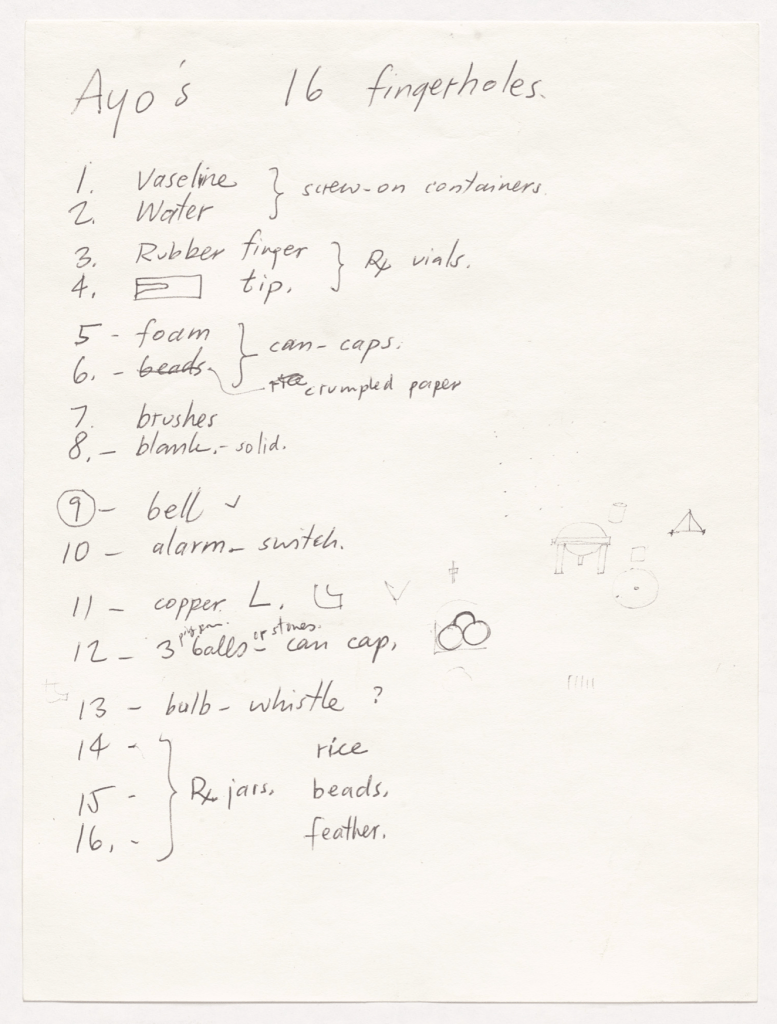

Throughout the many examples of Ay-O’s tactile devices presented in this essay, a persistent question emerges: what is the actual experience of these works? Most museum catalog descriptions omit the crucial detail of what material the finger encounters when exploring the piece. The Flux Cabinet offers a rare exception. A drawing created by Maciunas around the time he worked on the cabinet includes a list of contents for Ay-O’s drawer, providing insight into the tactile sensations the work was designed to produce [Fig 14]. It mentions Vaseline, water, rubber fingertip, bristle brushes, crumpled paper, bells, alarm switch, rice, beads, feathers, and more. This list demonstrates the practical way Ay-O’s Tactile List could be translated into materials employed in the work.

A similar list exists for another Maciunas interpretation of Ay-O’s Finger Box—referred to as “Ayo’s fingerhole set” in Maciunas’ undated instructions sent to Jean Brown in a letter and catalogued as a Finger Box (1964) in the Getty Research Institute archive.[20] The instructions list tactile materials for each of the 16 holes, including many found in the Fluxus Cabinet as well as others, such as sawdust and steel wool. An archivist or conservator photocopied this list from the original and attached it to the archival box holding the piece. However, a second set of contemporary instructions affixed to the box warns researchers examining the work to “resist the temptation” of inserting their fingers, as “the brittle rubber membranes will rip or even fall apart.” It was precisely an encounter with this piece at the GRI study room that sparked my interest in Ay-O’s touch devices and the constraints that material preservation concerns place on tactile engagement.[21]

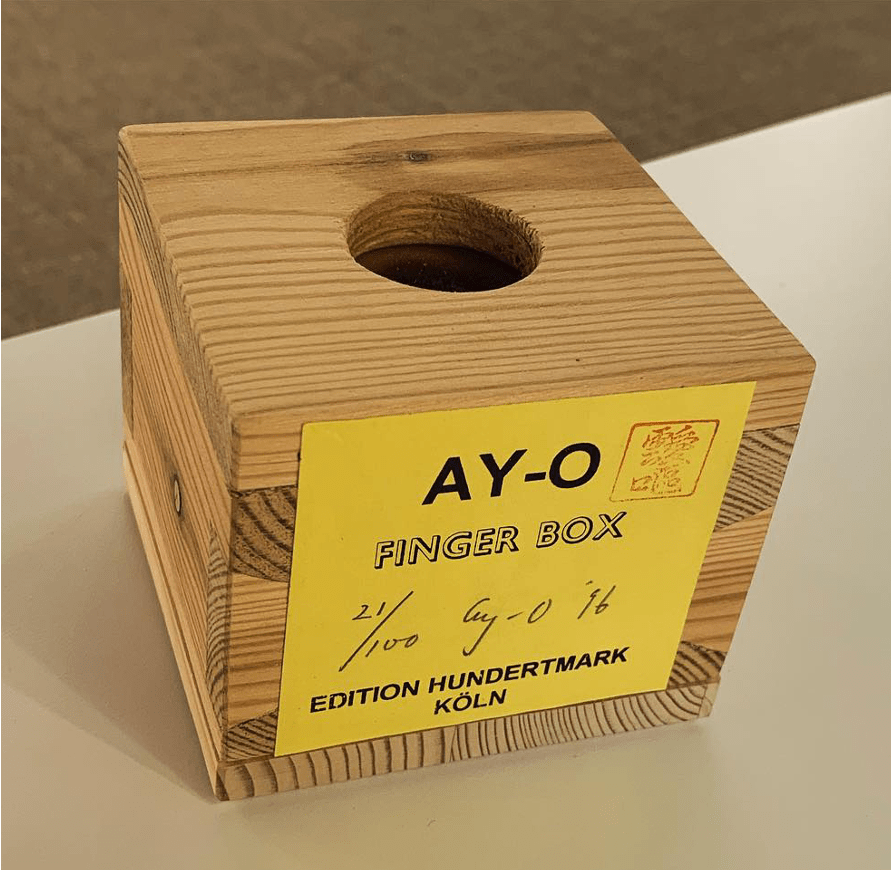

Many more variations of Finger Boxes exist, such as an early cardboard example dated 1964 with an orange label featuring Maciunas’ design, a cardboard version from 1965 that can be accessed at the Fondazione Bonotto online collection catalogue, and editions produced for various purposes beyond the key decades of Fluxus operations. These include an edition of Finger Box Kit (1991) for Fluxus’ thirtieth anniversary celebrations at the “Excellent 1992” festival in Copenhagen and an invitation to an Ay-O exhibition at the Emily Harvey Foundation in 1991. The most recent instances include a simple wooden version published by Edition Hundertmark Cologne and one produced as merchandise for the exhibition Ay-O: Hong Hong Hong at M+ Hong Kong in 2023.

Jon Hendricks in his Fluxus Codex (1980) categorized all of Ay-O’s Fluxus tactile devices as derivatives of the same concept, listing them under a single entry. What further unites most of these instances is that they were published as multiples, which now populate many contemporary art museum collections. Each has its unique story and features, such as the boxes that Ay-O dedicated to particular individuals – like those from the Archivio Conz that bear the artist’s signature and a simple phrase: “to Francesco.”

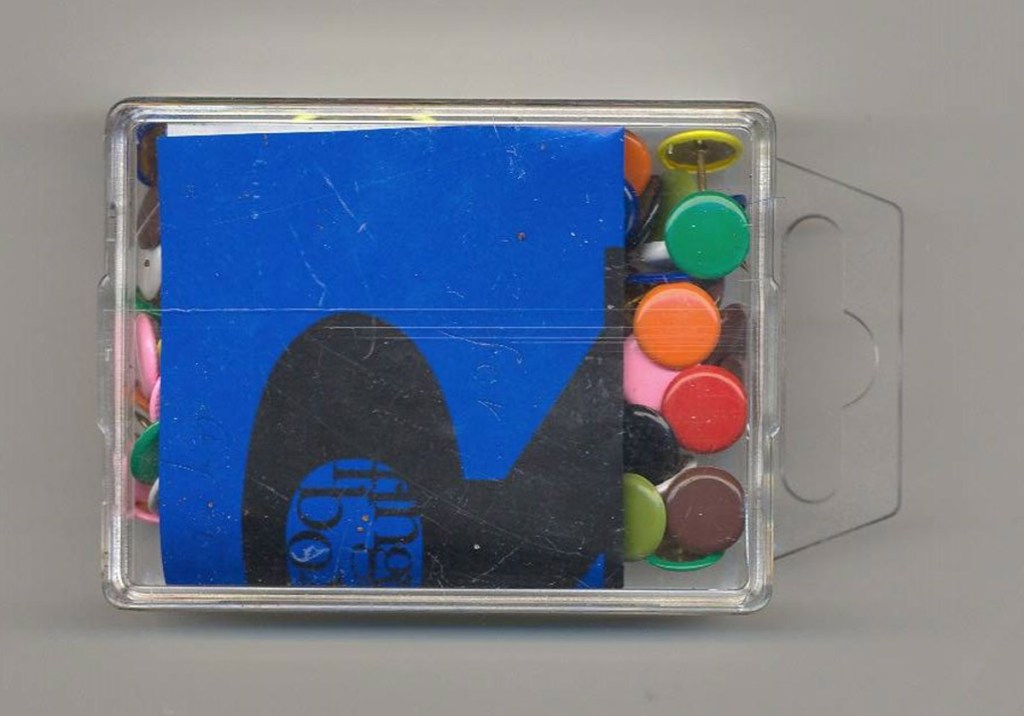

This tension between the uniqueness and therefore preciousness of each piece, their precarious material condition, and their intended mode of experience makes them a remarkable example of the complexities related to musealisation of Fluxus. Many different strategies have been employed to allow audiences to experience Fluxus forms as they were designed. One example is republishing initiatives, such as Barbara Moore’s Reflux Editions. [22] Interestingly, however, this initiative produced another generation of objects that enter museum collections and therefore become inaccessible for haptic examination. [23] Another strategy is to produce exhibition copies that preserve the original form and materials but exist solely to facilitate access to the original piece. An example of this approach is the Open and Shut case by Ken Friedman, produced specifically for Friedman’s 2023 show. [24] A third strategy involves emulating the tactile experience without reproducing the format of the piece, as represented by the vitrine designed for the 2007 exhibition at the Getty Research Institute. [25] There is also a creative approach – a playful artistic (self)reinterpretation exemplified by the simple box of pins with an Ay-O Finger Box label produced for the Fluxus Virus exhibition in Cologne in 1992.

Each of these strategies has its benefits and shortcomings, and although I do have my favourite, I am looking forward to learning more about possible solutions during the forthcoming Study Day.

Stay tuned for the follow up!

I would like to thank Kit Brooks for advice and sharing published materials on Ay-O, Midori Yoshimoto for her guidance on the literature and for generously sharing her own writing on his art, and Sally Kawamura for her assistance in making connections.

References:

[1] Maciunas’ set of fictious stories published by Jon Hendricks in the “Fluxus Newsletters” sections of Hendricks, Fluxus Etc, 284.

[2] David Michael Levin, The Body’s Recollection of Being (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985), 56 in Higgins, Fluxus Experience, 40.

[3] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 153.

[4] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 166.

[5] These twenty-one-essay series was printed monthly in the art magazine, Bijutsu Techo, from September 1986 (except for July 1987). All have been translated to English by Midori Yoshimoto and included in Over the Rainbow: Ay-O Retrospective 1950-2006 (Fukui: Fukui Fine Arts Museum and Miyazaki Prefectural Art Museum, 2006).

[6] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 166.

[7] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 166.

[8] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 167.

[9] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 168.

[10] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 167.

[11] Hendricks, Fluxus Codex, 173.

[12] Yoshimoto, “From Space to Environment,” 43.

[13] Brooks, Ay-O Happy Rainbow Hell, 143; Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 168.

[14] Brooks, Ay-O Happy Rainbow Hell, 52.

[15] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 168.

[16] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 168.

[17] Ay-O, “Over the Rainbow,” 174.

[18] Brooks, Ay-O Happy Rainbow Hell, 63.

[19] Yoshimoto, “From Space to Environment,” 29.

[20] https://www.getty.edu/research/collections/component/10Y447

[21] Wielocha, “Archival Explorations: Fluxus at the Getty Research Institute’s Special Collections.”

[22] ReFlux Editions was founded by Barbara Moore, a close associate of Fluxus leader George Maciunas, as a way to continue publication of Fluxus multiples, keeping them indefinitely in print. The works are collated from original vintage printed matter from Maciunas or his estate. The plastic boxes are either vintage or from original sources. See “ReFlux Editions at Printed Matter, Inc.,” e-flux, March 26, 2002, https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/43512/reflux-editions-at-printed-matter-inc

[23] See for example the ReFlux edition of Ken Friedman’s and George Maciunas’ Open and Shut Case – both the 1966 and the 1987 Reflux version are now in The MoMA’s Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection. See” https://www.moma.org/collection/works/128062 and https://www.moma.org/collection/works/132095

[24] Open and Shut Case (2023) produced for exhibition “92 EVENTS” hosted by Kalmar konstmuseum (08/02 – 23/04/2023). See: https://activatingfluxus.com/2023/02/25/episode-4-open-and-shut-case-1965-by-ken-friedman/

[25] in “Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art: Experimentations in the Public Sphere in Postwar Japan, 1950–1970” at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, March 6–June 3, 2007 at the Getty Center, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ay-O#/media/File:Ay-O-boxes.jpg

Bibliography:

Ay-O. “Over the Rainbow.” In Over the Rainbow: Ay-O Retrospective, 1950-2006, translated by Midori Yoshimoto. Fukui Fine Arts Museum and Miyazaki Prefectural Museum, 2006.

Brooks, Kit. Ay-O Happy Rainbow Hell. Smithsonian Books, 2023.

Hendricks, Jon. Fluxus Codex. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, 1988.

Hendricks, Jon. Fluxus Etc: Addenda I : The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection. Ink & Press, 1983.

Higgins, Hannah. Fluxus Experience. University of California Press, 2002.

Wielocha, Aga. “Archival Explorations: Fluxus at the Getty Research Institute’s Special Collections.” Activating Fluxus, August 19, 2023. https://activatingfluxus.com/2024/08/19/archival-explorations-fluxus-at-the-getty-research-institutes-special-collections/.

Yoshimoto, Midori. “From Space to Environment: The Origins of Kankyō and the Emergence of Intermedia Art in Japan.” Art Journal 67, no. 3 (2008): 24–45.

Featured Image: Ay-O, AY-O’s finger box No 29 (nd). Courtesy: Archivio Conz, Berlin