by Josephine Ellis

In a short essay first published in 1967, the art critic John Berger briefly problematized the relationship between the multiple and its conservation. More so than any other type of multiple, Berger’s concern was with multiples that actively accentuated movement, whether physically, virtually and/or conceptually. The condition of movement, Berger hypothesized, best positioned the multiple (though, not without limitations) as a disruptive force to art’s commodity status: the material contingency of such multiples, ultimately prone to damage, falter and breakdown, might undermine art’s glamorous allure as “magical, mysterious, incomprehensible.”[1] For Berger, art’s commodification, its otherwise quasi-spiritual valuation as “property,” was in part owed to the perception of art as “enduring and unique”[2]—beholden to the fallibility of its materials, however, and much to Berger’s amusement, such perceptions might be skewed. “It [the multiple]” Berger surmises, “does not even have a fixed and proper state in which it can be preserved: it is constantly open to change and alteration.” “Like a toy,” he suggests, “it wears out.”[3]

The multiples Berger refers to here can be attributed to those commonly associated with the post-war “kinetic art” revival—”kinetic art” here in quotations because, though not the subject of this short intervention, I am convinced that kineticism should refer less so to a specific type of artwork than it might encompass all works crafted from matter. Kinetic, from the Greek kinētikos meaning “of motion,” is matter’s persistent state, always in flux. (As philosopher Thomas Nail suggests, matter and motion are one and the same: “‘matter’ is [the] historical name for what is in motion.”[4]) Though not mentioned by Berger explicitly, these multiples first constituted the basis of Fluxus-affiliate Daniel Spoerri’s initial collection of the Edition MAT (multiplication d’art transformable), thematically clustered, as it was, around the matter of movement. When, in late November 1959, Spoerri established the first of three instalments of the Edition MAT, it was also the first attempt of its kind to build something of a concrete infrastructure around the multiple’s production and dissemination. For Spoerri, in fact, to be rendered a multiple, an artwork first and foremost had to move. Multiplication thus channeled forces already inherent to works of art: only then did multiplication make meaningful sense, effecting a further kind of transformation to that which already transformed.

Though, in discourses of contemporary art conservation, much has been made of artworks that appear in multiple instances (time-based media installations, for example), comparatively scant attention has been paid to the multiple itself.[5] Possibly, this has been in part due to the multiple’s somewhat enigmatic character, linked only loosely by implications of serialization.[6] If ultimately ambiguous in the type of art it continues to delineate, it has been the multiple’s historically situated critique of art’s commodification—and the perceived ubiquity of this function—that gives the multiple a semblance of specificity, setting it as a category apart from art forms previously replicable or reproduceable.[7] In what follows, I attempt to situate the multiple in another critical trajectory. Taking Spoerri’s logic of the multiple as my point of departure, gleaned from a mixture of Spoerri’s published writings and correspondences (both archived and reproduced in secondary literature), and drawing on critical theory both in and outside of conservation, I test the multiple as an object of conservation on the one hand, and multiplication as an expanded conservation gesture on the other. Ultimately, I suggest that to think multiplication as expanded conservation is arguably to urge for a kind of “complicity” with the conservation object. I am here adapting Petra Lange-Berndt’s suggestion to be “complicit” with materials. If as Lange-Berndt suggests, to be complicit with materials is to “investigate societal power relations” and “acknowledge the non-human,”[8] both of these themes, inseparable from each other, run throughought my grappling with the multiple as the object of conservation.

Introducing the Edition MAT

“The static objective work permits only quantitative multiplication of the fixed idea present within the model; even if it was widely disseminated, multiplication would not add anything to it.

For the animated work, either by itself or through the interaction of the viewer-collaborator, multiplication renders justice to the infinite possibilities of transformation.”[9]

These words by Spoerri open the Edition MAT’s first hybrid sales/exhibition catalogue. Printed and distributed on the occasion of the collection’s presentation at the Galerie Edouard Loeb in Paris, November 1959, this event would mark the first of a six month long run of exhibitions promoting the MAT multiples across Europe.[10] (In addition to Paris, exhibitions would also be held in Milan, London, Newcastle, Stockholm, Krefeld and Zürich.) Entering the Galerie, a visitor might have been confronted with motorized works such as Jean Tinguely’s Constante indéterminée (Fig.1; Fig. 2), a small gadget-like whizz thing, or Marcel Duchamp’s rotating printed discs in the form of his Rotoreliefs (Fig. 3). Other works, if not necessarily moving in themselves, become re-configured in the viewer’s perception. Victor Vasarely’s Keiho and Markab, for instance, both silk-screen prints whose patterns diffract through corrugated glass, appear to morph in and out of its prescribed design at the viewer’s slightest movements (Fig. 4). Finally, there would have been artworks calling for hands-on interaction, like Dieter Roth’s Book AA, its loose pages allowing for participants to make several of their own aesthetic arrangements (Fig. 5). Despite potential discrepancies in artistic renown—Duchamp by-then an already canonized figure in comparison to a young Roth, for instance—each work was equally priced at the equivalent of 200 Deustche Marks and, in theory, to be sold in editions of 100. Though the displayed works appeared to have been signed by the individual artists, this was only ostensibly so: the signatures would have been attached to the objects by means of labels either stuck, glued or ironed on, rather than directly inscribed. Chances were that it was not the artist that had affixed their own signature to their works, nor would they have actually assembled the works themselves. Often, these roles were assumed by Edition MAT’s very own instigator: Daniel Spoerri.

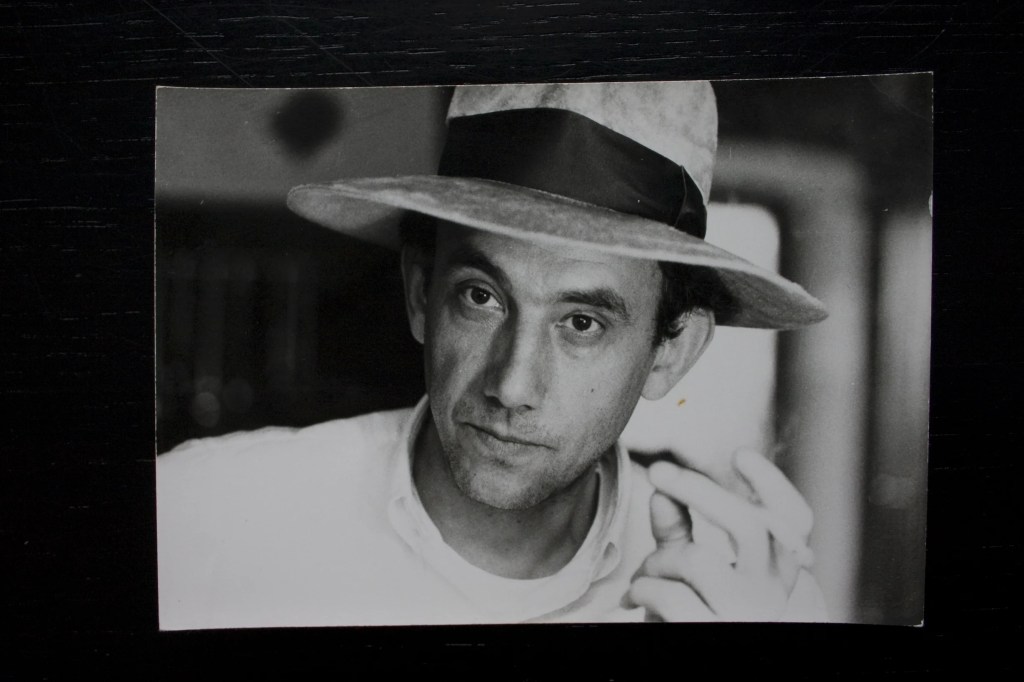

Sometimes associated with Nouveau Réalisme, at other times, with Fluxus (Fluxus artist Ken Friedman suggests Spoerri was shared between the two[11]), Spoerri, born Daniel Isaac Feinstein in 1930 to Romanian-Jewish parents in Galati, Romania, did not take up the name “Spoerri” until the early 1940s. When, along with his mother and siblings, forced to flee Nazi persecution—his father already arrested, captured, and most likely murdered—Feinstein found refuge in Switzerland with his adoptive uncle-to-be, Theophil Spoerri. With his forced nomadism as a child of war also in mind, perhaps it should come as little surprise that when Spoerri, a classically trained ballet dancer, eventually turned his attentions to the visual arts in the late 1950s (if not at first as an artist per se, but more so as publisher, curator, commissioner, producer[12]), it would be works perpetuating movement that were amongst those which most piqued his interests.[13]

Though the initial lineup of artists announced with the Galerie Edouard Loeb show changed throughout the exhibition’s later course, of the artists Spoerri successfully recruited at the beginning of his MAT project—including those already mentioned, Tinguely, Duchamp, Vasarely and Roth, and in addition, Raphaël-Jesús Soto, Jacoov Agam, Pol Bury, Josef Albers and Enzo Mari—five of this nine had previously exhibited together in 1955 at Galerie Denise René’s Le Mouvement, also in Paris. Organized by Vasarely and René, in its showcasing of international, multi-generational approaches to movement in art, Le Mouvement is often thought to mark the genealogical origins of post-war “kinetic art” practices.[14] Possibly it was from Vasarely that Spoerri picked up on the idea of multiplication[15]—writing in his “Le Manifest Jaune,” Vasarely declared:

“If the idea of the plastic work resided until now in an artisanal approach and in the myth of the “unique piece,” it is found today in the conception of a possibility of RECREATION, MULTIPLICATION and EXPANSION.”[16]

An edited version of this excerpt appears in the first MAT catalogue. Notably, reference to “the plastic work” is directly substituted for “conservation.”[17] Within the context of the Edition MAT, perhaps Vasarely might be understood as positing a new conservation, with multiplication very much in its repertoire. Vasarely’s provocation raises fascinating questions: what would it mean to think conservation as multiplication—and what would it mean for conservation to have the multiple as its “object”?

The Conservation/Agential Object

By “conservation object” or “object of conservation” I mean artworks material-discursively constituted by conservation which, beyond the artist, becomes a palimpsest of different hands and minds acting in line with wider socio-cultural permissions, limitations and orthodoxies.[18] Most recently, conservation theory has posited the conservation object as being “agential” in kind. That conservation objects might be agential proffers a re-working of conservation’s normative subject-object relations, in doing so, emphasizing the relational properties of active matter: matter might not only be active, but also activated as much as it also activates. To a certain extent, the hierarchical characterization of subject and object, deeply embedded in prevailing, Western philosophical traditions (of which some cultures of conservation has inherited), is flattened. It is not only the acting subject that conserves passive objects but objects themselves are considered capable of indicating the ways in which they might be cared for.[19]

As Hanna Hölling, Jules Feldman and Emilie Magnin put it, agential objects demand a reckoning with “what objects want.”[20] That Spoerri thought animate as opposed to static works were enriched by processes of multiplication is not unlike conservation’s framing of the agential object. Perhaps in this way, Spoerri’s understanding of the multiple might too be understood as hinting at objects’ agency: while animated objects might want to be multiplied, static objects appear ambivalent, if not resistant to it.

Unpacking “Agency”

Yet to further unfold the notion of the agential object in conservation—and, ultimately, to pose the multiple as such—it is perhaps necessary to address the question of what it means to suggest artworks have agency, as well as to clarify what is precisely meant by “agency.” Loosely defined, “agency” indicates a capacity to act. That artworks are thought to possess of a curious—because nonhuman—ability to act on people and things in their vicinity, not least, the viewer, has a long tradition in the history of art and material culture more broadly, manifest in various affective relations such as idolatry, iconoclasm, totemism, fetishism.[21] According to Horst Bredekamp, it was only from the 1960s that serious debates over the nature of artworks’ (though Bredekamp might prefer the term “image”) power to do so re-surfaced after intellectual stifling from the Enlightenment onwards, cast aside as expressions of either magical, religious or otherwise occult thinking.[22]

Anthropologist Alfred Gell famously set out his theory of artworks’ agency in the now classical Art and Agency, posthumously published in 1998. Rejecting (or as some commentators might have it, also oversimplifying[23]) the formal qualities and aesthetic functions of artworks, Gell put forth an understanding of the artwork socially conceived. In Gellian terms, artworks are a “system of action”: artworks are agential objects insofar that they are enmeshed in, mediate and make possible social relationships, for example, between the “initiator,” the maker, and “recipient,” the viewer. Important to note is Gell’s understanding of the category of “artwork”: first and foremost, artworks are objects that enchant—from the point of view of agency, artworks are objects endowed with technical virtuosity capable of captivating the viewer. As such, “artwork” for Gell refers just as well to Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa as it does a statue of the Hindu God, Shiva. As part of a wider causal nexus, artworks are not passive media or the mere effect of a cause but operates as one agentive component amidst multiple others.

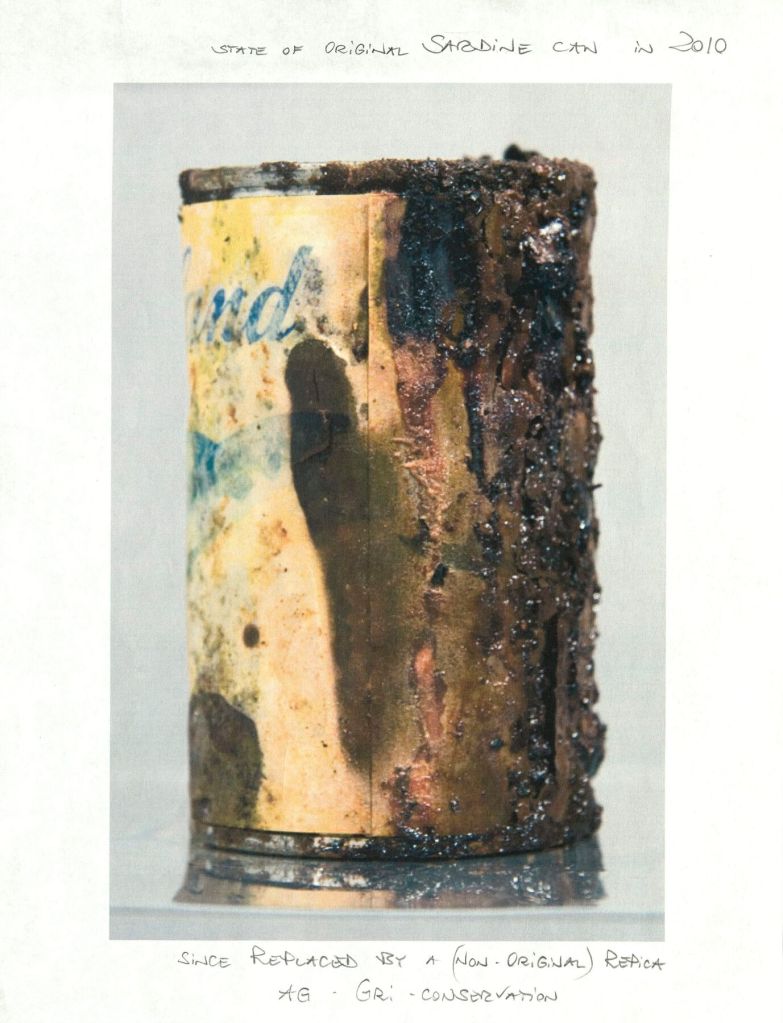

But agency is not distributed evenly amongst these agentive components. Because, at least for Gell, ultimately inanimate and thus, without capacity for cognition or intentionality, artworks’ agency is largely “efficacious.” This is to say that artworks are made to produce certain effects as conceived by the maker. Artworks are, for the most part thus, deemed “secondary” agents in contrast to the human actors who tend to assume the role of “primary” agents. Agency doesn’t begin with the artwork per se, but rather extends or acts as a prosthesis for human agency, such as the maker’s, which is distributed in and through the work (Gell’s claim here, building on semiotic theory, is that the viewer “abducts” the maker’s agency from the work by cognitive inference of the maker’s intentions). Beyond the scope of this intervention, but nevertheless important to mention is that the provocation to consider what objects want requires a still more radical account of agency than Gell’s—to suggest that objects want arguably affords to them a status above Gell’s secondary agent. Artworks might, as Hölling, Feldman and Magnin suggest, have “their own tendencies, propensities and trajectories [emphasis added].”[24] One example of artworks acting in excess of their human maker’s intentions could include the case of the exploding tin of sardines in Ben Patterson’s Hooked (1981) (Fig. 6). (This incident was also covered by a Radio Fluxus podcast episode.) Here, agency might merit consideration less so, as Gell does, from the level of the object, and more so at the level of matter.

If both constituted by and contingent on social relations, then, to remain agential qua Gell, artworks must be maintained in/as the relation that allows for the artwork’s ability to act in the first place. To conserve relationality might necessitate the sacrifice of material durability as conceived by the—though by-now, much contested—classical, largely Western sense of conservation. In certain indigenous cultures of conservation, originating from the American Southwest for instance, what might be considered a form of “ritual care”[25] (as Miriam Clavir does) necessitates the feeding of sacred objects, potentially harbouring a living, ancestral soul or spirit, with substances like corn meal and pollen.[26] This feeding, in turn, not only serves as a gesture of communal importance but also sustains, thus, the object’s own communal importance. Further still, to feed an object is not only to culturally nourish it as an act affirming its embeddedness in social relations, but quite literally, to keep it alive—indeed, for indigenous communities, “object,” as a representative of Western epistemes, might prove a moot term. Instead, objects are rather “Subjects” “Beings” or “Ancestors,” amongst others.[27]

A point of tension from conservation as a gesture of feeding might emerge from the classical conservation’s perspective that introducing foodstuffs into the object’s (or artwork’s in Gell’s sense) vicinity increases the risk of attracting insects, oft considered a major threat to objects’ and/or artworks’ material stability.[28] By way of this tension, resonances might be gleaned between the ritual feeding of sacred objects and the conservation of “kinetic multiples” insofar that the multiple’s agency arguably also hinges on the possibility of their eventual destruction (recall here Berger’s account of their susceptibility to wear out). That this might be the case is alluded to by Berger, who stipulates that the multiple’s movements reach beyond themselves to sensitize the viewer, not only to the work, but more importantly still, to the reality of the viewer’s wider environment.[29] Following the Gellian sense of agency, the multiple becomes agential in its mediatory movements between the viewer and their surroundings. If it can be accepted that the multiple’s forging of social relations stems from their capacity to move, then to conserve agency would be to conserve (perhaps as an expanded form of ritual care?) the multiples in and as their movements, or as their animacy, as Spoerri conceived of it.

Multiplication as Conservation?

But what does it mean to conserve the multiples in and as their movements/animacy—to conserve, thus, their agency? Writing in 1960 for the Münich-based student journal “nota,” Spoerri elaborates further, his approach to multiplication. Contrary to indications of the MAT multiples’ limited run, Spoerri suggests here that multiplication might be considered as a perpetually open-ended process:

“As soon as an image is in change, whether due to actual or merely apparent motion, it enters into an ongoing state of transformation, making it endlessly new and different. Because it is created through movement, multiplication can happen at any moment, as it is always changing and renewing itself over time.”[30]

For Spoerri, it appears that, to multiply an artwork is simply to add to another layer of transformation to the repertoire of that which anyways transforms—in line with the multiple’s movements in time and space, multiplication might also function as a kind of movement, but one that moves across time and space as the multiple becomes actualized in the present.

Once again, the cue for multiplication emerges from the artwork itself. That artworks might be, in Spoerri’s words, in an “ongoing state of transformation” and thus “endlessly new and different” alludes to the possibility of their becoming multiple in themselves. Here, he arguably strikes a resonant chord with the Bergsonian conception of nonlinear time.[31] Philosopher Henri Bergson accounted for time most influentially through the notion of duration. According to duration, time ceaselessly gushes forth. It does not do so, however, from past to present to future. Vehemently rejecting the classical science’s spatialized, homogenous time, Bergson thinks duration as akin to the experience of a memory which, in turn, tells of the past’s persistence in the present. The past in its persistence opens itself to what Bergson calls “pure heterogeneity”—that is, continuous “invention, the creation of forms, the continual elaboration of the absolutely new.”[32] Spoerri’s sense of artworks’ multiplicity lines up with the heterogeneity of Bergson’s duration. That a work of art can be thought of as in a state of continuous invention, creation and elaboration is perhaps what Berger meant when he described the “kinetic multiple” as lacking a fixed state. Without a fixed state, each state might be considered as of equal value as the next—to multiply a work then could count as just another one of its new states, meaning that, as Spoerri posits “multiplication can happen at any moment.”

This post is dedicated to Daniel Spoerri who, perhaps best known for his Tableaux-pièges (at times, to his annoyance), sadly passed on November 6, 2024.

[1] John Berger, “Art and Property Now,” in Landscapes: John Berger on Art, ed. Tom Overton (London: Verso, 2016), 161.

[2] Berger, “Art and Property,” 164.

[3] Berger, 163.

[4] Thomas Nail, Theory of the Object (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 25.

[5] An exception to this is Isabel Plante, “Kinetic Multiples: Between Industrial Vocation and Handcrafted Solutions,” in Keep It Moving? Conserving Kinetic Art, eds. Rachel Rivenc and Reinhard Bek (Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2018), 104-112.

[6] Friedrich Tietjen alludes to this by paraphrasing Gertrude Stein’s famous tautology: “Ein Multiple ist ein Multiple ist ein Multiple”[6])Friedrich Tietjen, “The Making of: the Multiple,” in Kunst ohne Unikat. Multiple und Sampling als Medium: Techno-Transformationen der Kunst, ed. Peter Weibel (Köln: Walther König, 1999), 82.

[7] Tietjen, “The Making of: the Multiple,” 83.

[8] Petra Lange-Berndt, “Introduction: How to Be Complicit with Materials,” in Materiality, ed. Petra Lange-Berndt (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2015), 16-17.

[9] Daniel Spoerri, Edition MAT: Multiplication d’Oeuvres d’Art (Paris: Galerie Edouard Loeb, 1959), n.p.

[10] The staging of temporary exhibitions was a way for Spoerri to avoid succumbing outright to the gallery system, whose prices, Spoerri noted, were exorbitant. Vatsella, 36.

[11] Ken Friedman, “The Early Days of Mail Art: An Historical Overview,” in Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology, ed. Chuck Welch (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 1995), 6.

[12] Spoerri’s role in the Edition MAT raises similar ambiguities to the one George Maciunas would later assume in the manufacturing of Fluxus multiples: that is, a more administrative if still authorial position, though not necessarily an outright artistic authorship in kind. For differing accounts of Maciunas’ convoluted authorship status in Fluxus see Julia Robinson, “Maciunas as Producer: Performative Design in the Art of the 1960s, Grey Room, no.33 (2008): 56-83; Colby Chamberlain, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2024).

[13] Tentatively discussing his plans for the Edition MAT in early 1959, for example he conceived of his project as a “refuge” for those interested in the problem of movement. Vatsella, 36.

[14] Pamela Lee, Chronophobia: On Time in the Art of the 1960’s (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 96.

[15] Archiv Sohm.

[16] Victor Vasarely, Le Mouvement: Notes Pour un Manifeste, 1955. Fondation Vasarely, Aix en Provence. Last accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.fondationvasarely.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Le_Manifeste_Jaune_Victor_Vasarely.pdf.

[17] Vasarely quoted in Spoerri, Edition MAT, n.p.

[18] Rebecca Schneider and Hanna B. Hölling, “Not, Yet: When Our Art is in Our Hands,” in Performance: The Ethics and Politics of Conservation and Care, Volume I, eds. Hanna B Hölling, Jules Pelta Feldman, Emilie Magnin (London: Routledge, 2023), 51. Salvador Muñoz Viñas first introduced the notion of the object of conservation in Salvador Muñoz Viñas, Contemporary Theory of Conservation (Oxford: Elsevier, 2005)

[19] The idea that artworks might indicate their own conditions of care was first formulated in Hanna B. Hölling, “Introduction: Object—Event—Performance,” in Object—Event—Performance: Art, Materiality, and Continuity since the 1960s, ed. Hanna B. Hölling (Bard Graduate Center: New York, 2022), 27. This was more recently picked up again specifically in relation to performance in Hanna B. Hölling, Jules Pelta Feldman, and Emilie Magnin, “Introduction: Caring for Performance,” in Performance,2-3.

[20] Hölling, Feldman and Magnin, “Introduction,” 3.

[21] Caroline van Eck, Art, Agency and Living Presence: From the Animated Image to the Excessive Object (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2015), 45-66.

[22] Bredekamp suggests no less than five principal reasons for this…Edgar Wind…Horst Bredekamp, Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2021), 1-7.

[23] Hannah Baader and Ittai Weinryb, “Images at Work: On Efficacy and Historical Interpretation,” Representations, no. 133 (2016): 10.

[24] Hölling, Feldman and Magnin, 2.

[25] Miriam Clavir, Preserving What is Valued: Museums, Conservation, and First Nations (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2002),95.

[26] Miriam Clavir, Preserving What is Valued, 94.

[27] Aaron Glass, “Introduction: For the Lives of Things – Indigenous Ontologies of Active Matter,” in Conserving Active Matter, eds. Peter N. Miller and Soon Kai Poh (New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2023), 225-226.

[28] Miriam Clavir, Preserving What is Valued, 94.

[29] Berger, “Art and Property Now,” 163.

[30] Spoerri, “The Multiplied Work of Art,” 216.

[31] For applications of Henri Bergson’s conception of time in conservation and Fluxus, see Hölling, Paik’s Virtual Archive, 93-108; Hannah Higgins, “Introducing “Fluxus with Tools,”” in Object—Event—Performance: Art, Materiality, and Continuity Since the 1960s, ed. Hanna B. Hölling (New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2022), 51.

[32] Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution, trans. Arthur Mitchell,(London: Macmillan and Co, 1922), 11.

Featured image from https://www.spoerri.at/en/daniel-spoerri-en.