by Josephine Ellis and Aga Wielocha

During the fourth Fluxus Study Day, the Activating Fluxus Team explored Wiesbaden, home to the historic “Fluxus: Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik” of 1962. The festival, often regarded as Fluxus’s founding moment,[1] unfolded in the auditorium (Hörsaal) of the Städtischen Museum Wiesbaden between September 1-23, 1962. Although comprised of as many as ten concerts,[2] the event is primarily remembered through Hessischer Rundfunk’s short documentary footage[3] featuring excerpts of several Fluxus performances, including its most controversial performance: Philip Corner’s Piano Activities (1962), where Dick Higgins, George Maciunas, Ben Patterson, Wolf Vostell, and Emmet Williams dismantled a piano using crowbars, saws, hammers, and their bare hands.[4]

This Study Day, expertly organized by Elke Gruhn—a longtime Wiesbaden resident, cultural worker, curator, Fluxus advocate, and Activating Fluxus associate researcher—aimed to examine this founding myth and trace Fluxus’s legacy throughout the city and its surroundings.

STOP#1 – Block Beuys, Hessische Landesmuseum Darmstadt and the Fluxus Abendessen with pink champagne

Our tour began at the famous Block Beuys—a seven-room collection of almost 300 works within the Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt. The works, created by Beuys between 1949 and 1972 and installed by the artist in 1970, remained untouched after the artist’s death in 1986 until the museum’s renovation between 2007 and 2014. This modernization replaced the aged fabric walls and carpets that had served as backdrops to Beuys’ interventions with a white cube layout, sparking controversy among Beuys scholars. Our late evening tour, guided by museum curator Dr. Gabriele Mackert, though undocumented due to internal museum restrictions, was magical. With few other visitors present, we had a unique opportunity to experience the installation intimately and engage in conversations about the authenticity of contexts, the challenging decisions museums face in remaining relevant to today’s public, maintaining increasingly sophisticated conservation standards, and staying true to artists’ intentions.

STOP#2 – Ute and Michael Berger’s collections

Whatever its origins, this relationship flourished over time, with the Bergers supporting numerous Fluxus artists and events while building an art collection, much of which emerged through an exchange system – artists would stay for extended periods at the Bergers’ premises, leaving behind works created during their residencies. The roster of artists hosted by the Bergers includes Joe Jones, Nam June Paik and Ben Patterson, who took up an extended residence there after returning to artistic practice in the late 1980s.

In her essay published in The Fluxus Reader, Hannah Higgins observed that “with the exception of a small, privately owned Fluxus Museum, called the Fluxeum and run by Michel and Ute Berger, Wiesbaden is more a run-down bathing resort than a Mecca of contemporary art.”[5] While Higgins’s critical assessment of the city remained to be explored, we began our tour by investigating this notable exception. On Thursday morning, we journeyed by bus to Erbenheim, a borough of Wiesbaden, to visit Bergers’ collections. Though they weren’t present at the historic 1962 Fluxus concert, these Wiesbaden-based couple of entrepreneurs, businesspeople, and collectors of everyday objects and art have become instrumental in preserving the Fluxus legacy in the city. The story of their first encounter with Fluxus exists in many versions, and like many tales surrounding Berger’s collections and collecting practices, their historical accuracy remains delightfully uncertain. One account describes a 1973 meeting with Robert Filliou, who incorporated one of Berger’s products into an artwork – a piece the Bergers subsequently purchased, launching their collection. The second version, shared by Michel Berger during our visit, tells of a simpler beginning: a friend’s request to pick up Joe Jones from the Wiesbaden train station.

Beyond their art collection, the Bergers have assembled various themed collections, including one dedicated to Persil – the iconic German laundry detergent brand – along with collections devoted to onions and vintage enamel advertising signs. Their premises also house the “Klooseum,” derived from the German word Klosett (toilet) – a museum showcasing items related to the final stages of the digestive process. While the Bergers’ collections are officially not on display and therefore closed to the public, we were granted rare access thanks to Elke Gruhn’s longstanding relationship with the couple.

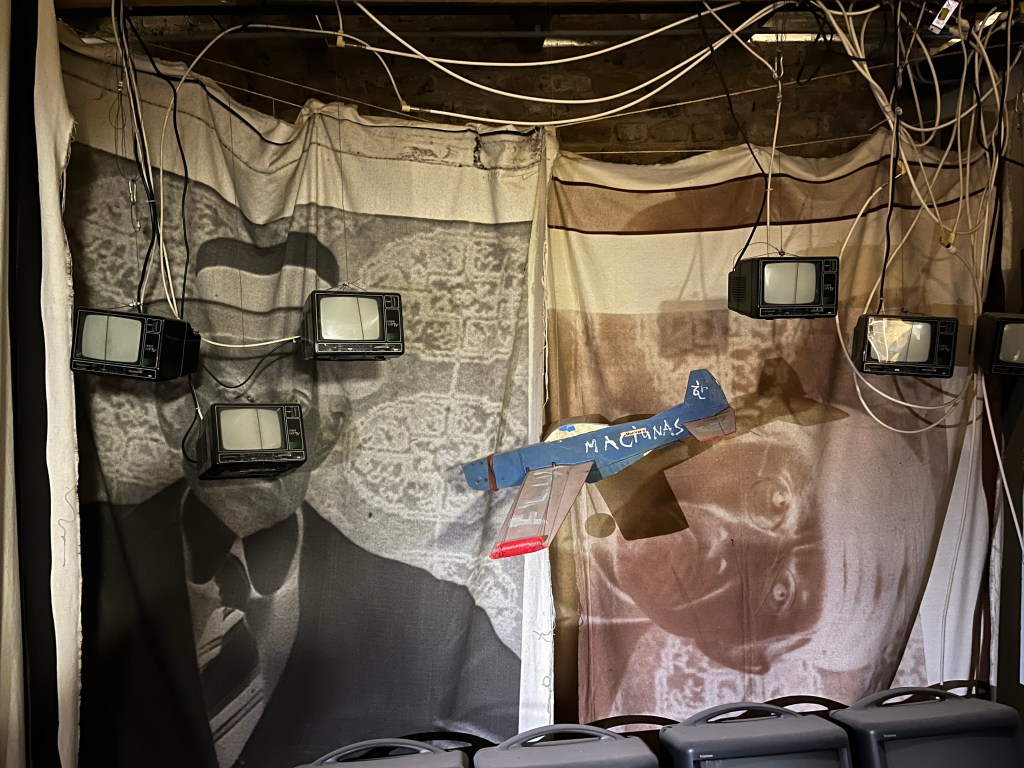

Our journey through this bizarre, sometimes overwhelming accumulation of objects, where distinguishing between art and stuff becomes an impossible task, was guided by Berger himself. Yet despite the collection’s distracting nature, we managed to keep our focus on Fluxus traces. The highlights included an impressive library containing seemingly every book and catalogue ever published about Fluxus, Ben Patterson’s former studio, an impressive (though unfortunately non-functional) video installation by Nam June Paik exploring Fluxus’s Wiesbaden connections, and a life-size replica of Joe Jones’s “Music Store” displaying the artist’s subtle musical machines.

The visit culminated in the “Church of Humor”—a deconsecrated church that since the late 1970s has housed the Fluxeum, a museum dedicated to art of Fluxus and beyond. This unique space, now adorned with Nam June Paik’s TV-sculpture placed in the former altar niche, has witnessed numerous significant art events over nearly half a century. These include one of Marina Abramović and Ulay’s first performances in 1978 and various Fluxus-related events, including the 2002 iteration of “Die Flux-Messe” (Flux Mass). There, against the backdrop of art adorning the church’s walls, we shared a delicious lunch of homemade pumpkin soup, prepared by Elke and heated in what was once Nam June Paik’s studio kitchen, now relocated to the former sacristy. As we listened to Berger’s stories over our meal, a special dessert awaited us—each visitor was granted the opportunity to play one of Joe Jones’s installation of music machines installed in the church’s choir.

We left the place amazed and somewhat bewildered, pondering the future of this unique collection. While its institutionalization would allow broader public access to these important art historical traces, such a change would inevitably compromise something essential: the collection’s peculiar context and the possibility of direct, informal interaction with art that makes it so special. We felt privileged to have been granted such a rare experience – an encounter with living history that will stay with us for a long time, reminding us that sometimes the most interesting ways to experience art happen not in pristine museum halls, but in spaces where art and life intertwine in often unexpected ways.

STOP#3 – Museum Wiesbaden: Retrospective of Alison Knowles and the remnants of 1962 festival

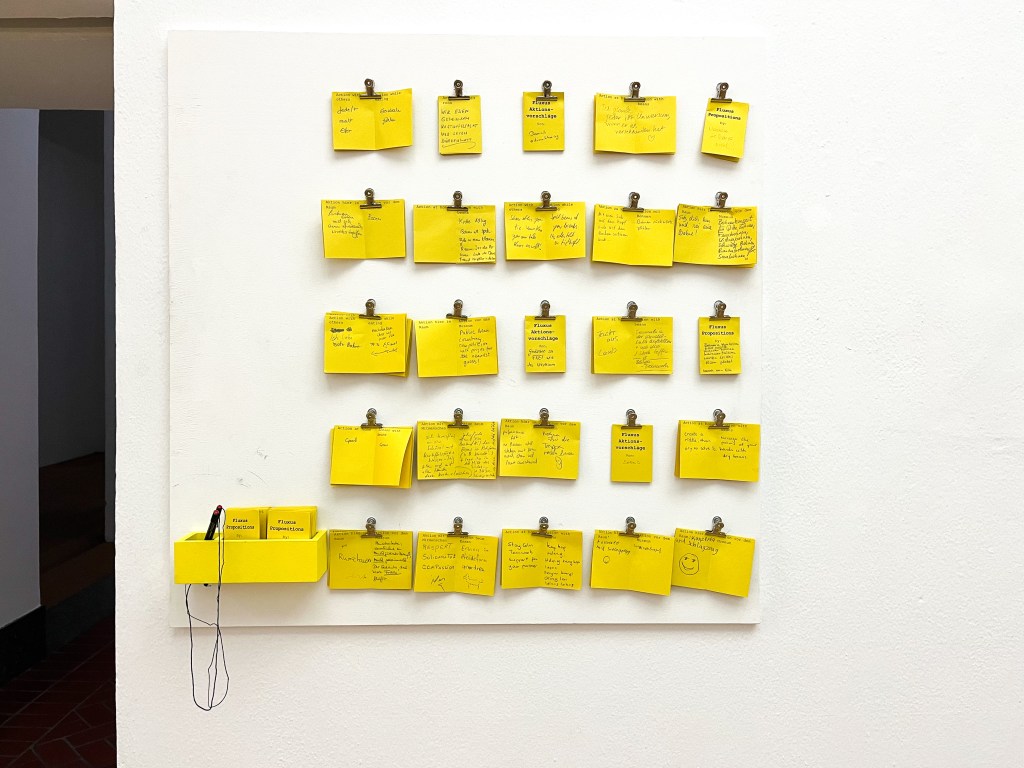

Despite its seminal place in Fluxus’ history, allusions to Fluxus in the Museum Wiesbaden are scarce. Had it not been for Alison Knowles’ retrospective currently on display (between 20th September 2024 and 26th January 2025), Fluxus might not have been visible at all, save for one or two catalogues in the Museum’s shop. Knowles too had been an active participant in the 1962 performances that took place in Museum’s auditorium. Attesting to Knowles’ Fluxus entanglements as well as the peculiarities of her own practice as an individual artist, the Knowles retrospective sought to capture the breadth and dynamism of her oeuvre, ranging from printmaking to performance, food-based works and poetry. Though a few artworks allowed for interaction, as with any Fluxus or Fluxus-related exhibition, it is acutely noticeable when things are otherwise placed behind protective measures, put in vitrines or cordoned off, as was the case with the majority of Knowles’ works. This was all the more emphasized by the fact that some members of the extended Activating Fluxus team had witnessed a few of the displayed artworks in a radically different context during a Study Day almost a year prior at the Archivio Conz, Berlin. As part of the Study Day, some of Knowles’ works had been selected for an “activation roundtable” in which they were freely out in the open, closely observed, picked up, rattled and shaken. This experiential contrast draws heightened attention to institutional shapings of what and how art might come to be valued—values not necessarily inherent to the artworks themselves.

If the Museum’s place in Fluxus’ history went somewhat amiss in the Museum itself, then its behind-the-scences collection and archival holdings told a completely different story. We were generously treated to several infamous props, relics and leftovers from the 1962 performance, not least the ink-soaked tie from Nam June Paik’s Zen for Head. It is perhaps in this trove of things through which Fluxus lurks, but not quite lives, on, awaiting interest form researchers and occasionally re-surfacing for exhibitions.

STOP#4 – Fluxus around town: Nassauischer Kunstverein, Museum Reinhard Ernst, House of Dust and the Bunker

One recurring theme throughout our visit to Wiesbaden was the sheer variety and juxtaposition of spaces for art and material culture more broadly. Starting with the Nassauischer Kunstverein, we were led by Elke to a floor in the building currently not in use as an exhibition space—instead, leaning against the wall in the dark, a row of chairs from the Museum Wiesbaden’s auditorium that visitors would have used during Fluxus’ Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik in 1962. Situated a short walk away from the Kunstverein is the Museum Reinhard Ernst which opened recently in June 2024, where we were given a guided tour around part of the permanent exhibition, “Farbe ist Alles!” by curator Lea Schäfer. If the Museum Reinhard Ernst is something of a white cube aesthetic par excellence – the impressive building, desgined by architect Fumihiko Maki – then the Luftschutzbunker (air raid bunker), the potential site of a (post-)Fluxus project in the works, offered a striking point of contrast. Built in 1939, the bunker was also that which Wiesbaden’s white flag of surrender was flown from during World War II. As explained to our team by architect Michael Müller as we toured around the bunker, there are ongoing plans for the bunker to be transformed into a Fluxus museum of sorts. Shifting the setting to the outdoors, Alison Knowles’ 3D printed House of Dust rounds off an ecclectic mix of spaces, produced by tinyBE in 2021 for their exhibition of temporarily inhabitable sculptures “living in a sculpture” and initiated by curators Cornelia Saalfrank and Katrin Lewinksy. The House of Dust, beginning in 1967 as a computer-generated poem and has, since then, taken on multiple different manifestations, including physical house-like structures, firstly in New York, then California, and now, Wiesbaden. Remarkably, the House, situated in Kranzplatz (which itself boasts of an interesting history, cultivated as a thermal spring facility by the Romas in the first century AD), has persisted relatively unscathed.

STOP#5 – Fluxus playground at the Schloss Freudenberg

Drawing on Joseph Beuys’ concept of the social sculpture—stated very simply, that society itself is a work of art—the Schloss Freudenberg, a castle-esque villa turned artwork populated playground, is something of a total work of art, with its visitors (mostly families with young children), running through its grounds in and amongst art objects, also included in the art’s workings. If these objects were precious, then they were not protected by usual “safegaurding” measures such as vitrines but perhaps made all the more so precious by a patina of sorts, accumulating experiential traces of the special memories made there. Not wholly dissimilar to the children, our team happily basked in the free spirit of play, making the most of the artworks and/or apparatus on offer, from humming basins of water to large slides and swings.

STOP#6 – Köln. Ursula Burghardt and Benjamin Patterson at the Ludwig Museum, Fluxus Virus car park and a Museum of Museums

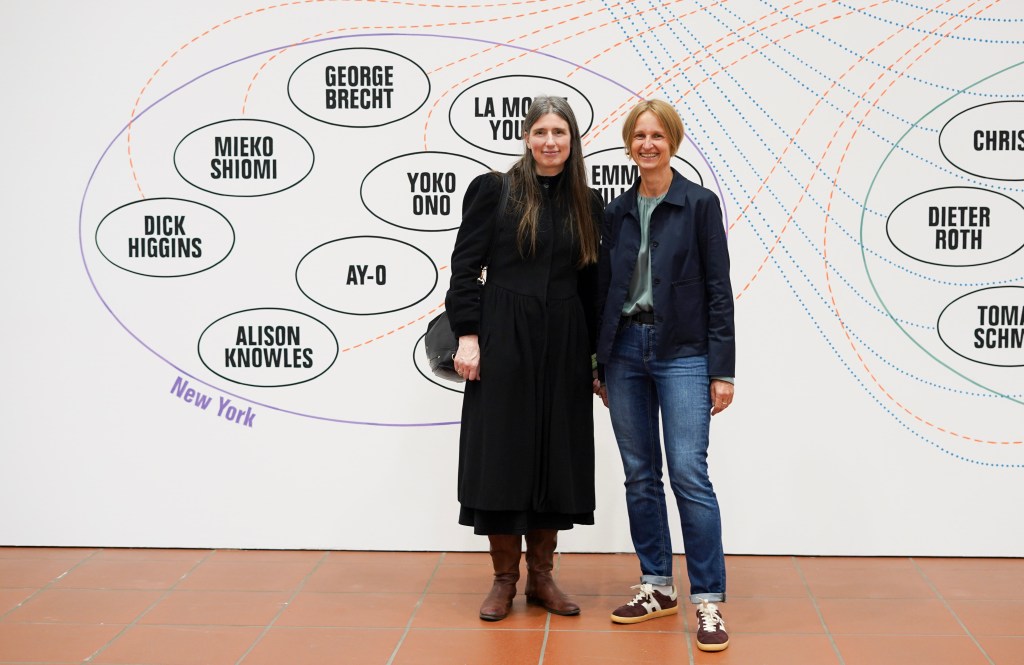

Our tour culminated in Köln with three final stops. Firstly, the Ludwig Museum’s exhibition “Fluxus and Beyond: Ursula Burghardt and Benjamin Patterson” (October 12, 2024 – February 9, 2025), sought to entwine the postwar, artistic legacies of Patterson, a prominent Fluxus member and Burghardt who, though in and out of the Fluxus orbit, mostly stayed on its peripheries. It was in 1960 in Mary Bauermeister’s Köln studio where Patterson and Burghardt first crossed paths. From the works displayed at the Ludwig Museum, it might be gleaned that both artists, resonant with the Fluxus and arguably wider neo-avante-garde concern for complicating the relationship between art and life, gave expression to the everyday through an engagement with different materials and materialities. While Burghardt often rendered everyday objects into metal, zinc and aluminum structures, Patterson arguably leaned more so on a kitsch aesthetics, appropriating knick knacks and toys powerfully (perhaps purposefully?) invocative of postwar Euro-American production and consumer culture.

Following on from this, our team were lucky to meet with legendary gallerist and patron of Fluxus and intermedia, Christel Schüppenhauer. Schüppenhauer, who, in October 1980, founded Pragxis Gallery in Essen-Kettwig, (in1985, renamed to Galerie Schüppenhauer and, in 1987, relocated to Köln), is perhaps best known in Fluxus histories for staging the exhibition, “Fluxus Virus” in Köln, 1992. Notably, part of the exhibition took place in the Kaufhof-Parkhaus (Kaufhof car park). Led by Schüppenhauer to the upper floors of the Parkhaus (including a comical struggle from our team members to operate the Parkhaus’ lift), we imagined the scene of the exhibition to the sound of Schüppenhauer’s reminiscing and admired the striking view of the Kölner Dom (Köln Cathedral).

For the grand finale of our Study Day, we whizzed round the Wallraf-Richartz Museum’s exhibition “A Museum of Museums: Time Travel Through the Art of Exhibiting” (October 11, 2024 – February 9, 2025). A self-conscious reflection of the history of the politics of display and the art of viewing, beginning with cabinets of curiosities and ending with the possibilities offered by virtual experiencing—and artistic concepts of the museum proposed by John Cage and Daniel Spoerri situated somewhere in between.

[1] This claim remains debated, see e.g. Owen F. Smith, Fluxus: The History of an Attitude (San Diego: San Diego State University Press, 1998), 25.

[2] Meticulously described by Henar Rivière Ríos in Petra Stegmann, ed., “The Lunatics Are on the Loose …”: European Fluxus Festivals 1962-1977 (Potsdam: Down with Art!, 2012), 49–92.

[3] Fluxus Festspiele neuester Musik Hessenschau (Hessischer Rundfunk), 11 September 1962, 5:19 min (as referenced in Stegmann, 515), available online.

[4] Richard O’Reagon, “There’s Music – and Eggs – in the Air!”, The Starts and Stripes, 21 October 1962, p. 11.

[5] Ken Friedman, ed., The Fluxus Reader (Chichester: Academy Editions, 1998), 49.

Featured image: Leftovers after the Fluxus-Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, 1962 at Städtisches Museum, Wiesbaden. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Sohm Archive, acquired in 1989. Photographer: Hartmut Rekort. Source.

All the photographs from the event featured in this essay are authored by Activating Fluxus team.