by Aga Wielocha

Getty Research Institute (GRI) is an invaluable repository of information on Fluxus, and a place of pilgrimage for Fluxus scholars and enthusiasts. Most existing publications concerning Fluxus mention sources from GRI special collections, yet this treasure trove continues to offer fresh insights, inviting researchers to uncover new dimensions of this complex artistic phenomenon.

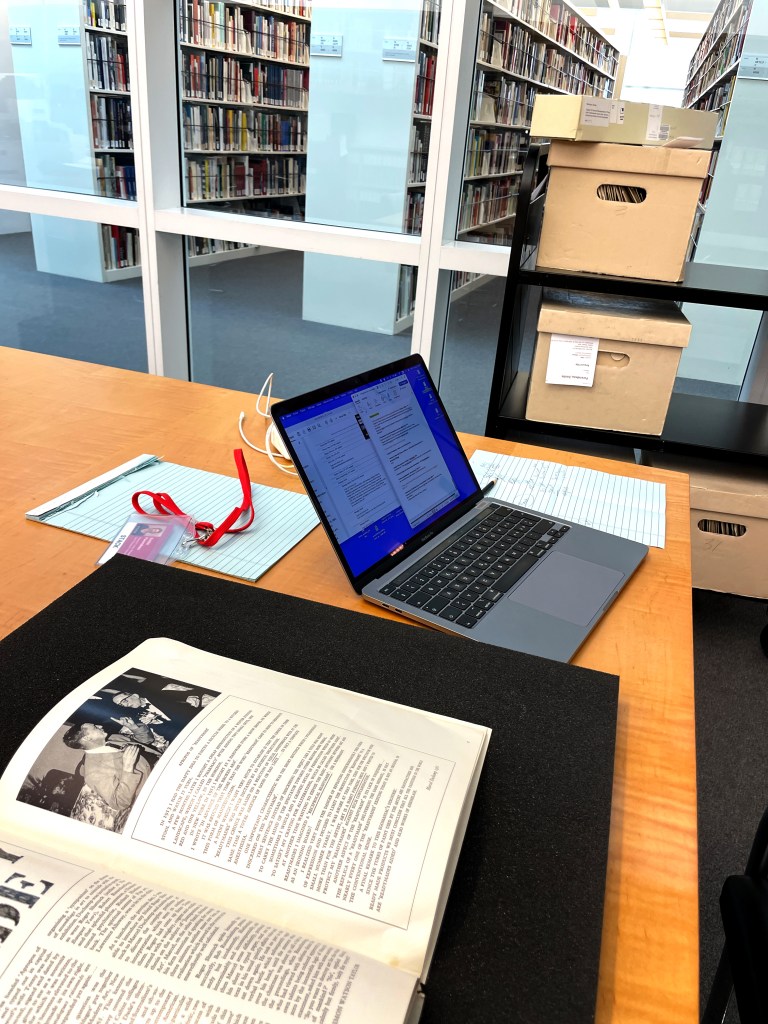

Navigating the GRI resources can be tricky, especially for a multifaceted network like Fluxus. I recently returned from a residency at the Getty Conservation Institute, during which I was able to engage with the GRI special collections for my Fluxus-related research. For one week I was also joined by Activating Fluxus associate researcher Emilie Parandeau, who was gathering information for her doctoral dissertation on the processes behind the production of multiples published by George Maciunas in the 1960s and 1970s. This blog post offers observations and guidance on navigating the complexity of GRI collections. It also shows how the legacy of art that often lacks a single, tangible outcome can be collected, accessed, and appreciated in a different, perhaps more personal and direct way —through direct access to archival material rather than through beholding of museum displays.

GRI houses approximately 500 special collections, containing rare and unique materials in selected areas of art history and visual culture, spanning from the 15th century to the present. These collections encompass a wide range of items, including prints, letters, photographs, audiovisual materials, manuscripts, sketchbooks, and albums among others. According to the GRI’s mission statement, these resources, pertaining to various collecting areas ranging from ‘Alchemy’ to ‘Video and Performance’, have been selected for their research value to art historians and scholars in related fields. They not only provide diverse perspectives on artistic production and its contexts, but also “illuminate intellectual exchanges that fostered creative collaborations” 1. A wealth of Fluxus-related information is housed across various GRI collections. While I’ll highlight the most significant ones below, it’s important to note that the mark of this rhizomatic network resistant to a narrow definition, can be encountered in numerous, often unexpected places.

The Jean Brown Papers (bulk 1958-1985), acquired as early as 1988, stand as the richest and most important collection of Fluxus-related material at the GRI. Despite the term “papers” in its title, this archive extends far beyond paper-based documents. Jean Brown (1916-1995), a librarian and art collector, dedicated her life to building a comprehensive study collection of avant-garde materials. Consequently, alongside extensive documentation and printed matter this collection houses a significant ensemble of art objects, both multiples and unique pieces, some created specifically for Brown. Reflecting the collector’s broad artistic interests, the archive extends beyond Fluxus to encompass contributions from artists involved in happenings, concrete and visual poetry, sound art, new music, mail art, copy art, rubber stamp printing, and video and performance art. This diverse range not only showcases Brown’s expansive curiosity but also provides a comprehensive overview of experimental art forms from the period.

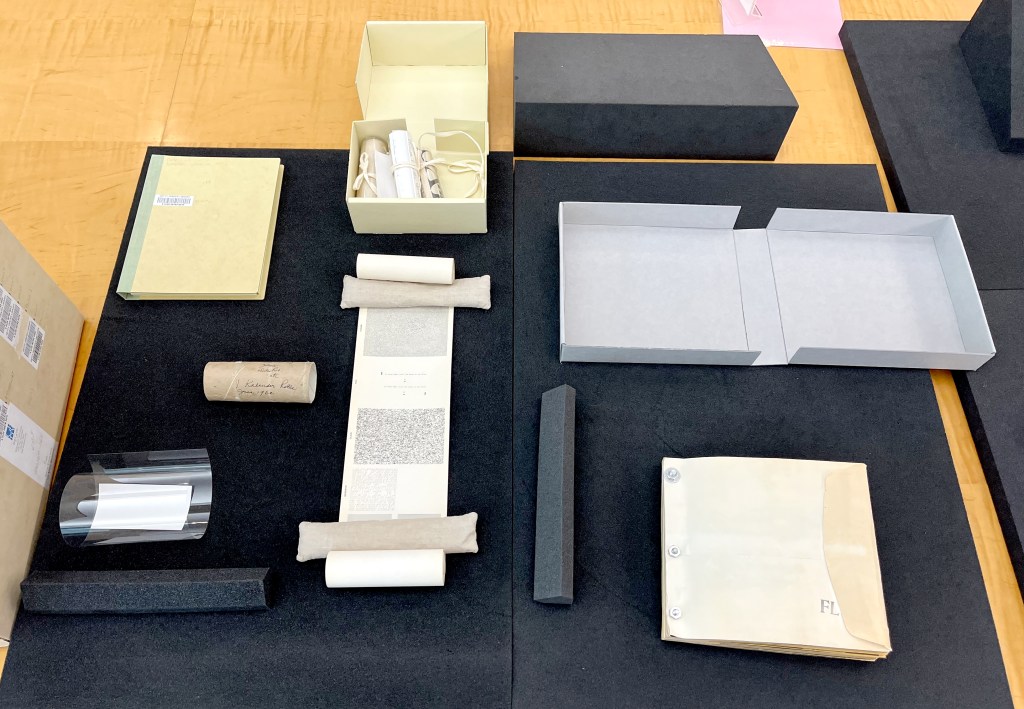

This collection offers a rare privilege: the chance to interact directly with iconic Fluxus objects. Visitors to the GRI can experience these artworks hands-on in the Special Collections reading room—an opportunity rarely available in museum settings. The pieces, primarily catalogued in “Series VI. Art objects, 1958-1986,” are arranged alphabetically by creator. The series boasts works by artists such as Joseph Beuys, George Brecht, Robert Filliou, Ken Friedman, Milan Knížák, George Maciunas, Nam June Paik, Dieter Roth, Takako Saito, Mieko Shiomi, Ben Vautier, Wolf Vostell, and Robert Watts. It includes emblematic pieces like Fluxus 1 (1962-64), Fluxkit (1965), and Flux Year Box 2 (1966), alongside lesser-known but equally intriguing works such as Ben Patterson’s Hooked (1980), featured in our Radio Fluxus podcast. One notable item, often discussed in conservation discourse,2 is George Maciunas’s Fluxmouse No. 1 (1973)—a dead mouse preserved in alcohol within a labeled glass jar with a typed label describing history of the mouse’s death. Additional artworks, primarily on paper, including prints, drawings, mail art, poetry, and scores, can be found in “Series I. Artists’ files”.

The Jean Brown Archive, as one of the first collections acquired, holds special significance for the GRI. It became a cornerstone in the formation of the Special Collections and greatly influenced their further development. Perhaps if this acquisition had not gone through, other collections featuring Fluxus artists might not have been acquired later. These collections include:

- Allan Kaprow papers 1940-1997

- Robert Watts papers 1883-1989 (bulk 1940-1988)

- Heinz Ohff collection of Wolf Vostell papers, circa 1962-2007

- Dick Higgins papers, 1960-1994 (bulk 1972-1993)

- Carolee Schneemann papers, 1959-1994

- Harald Szeemann papers, 1800-2011, bulk 1949-2005

- Emmett Williams Archive

- Emily Harvey Gallery records

As the Getty website is currently transitioning between two versions, there are various ways to access GRI resources. My favorite place for starting exploration of special collections is the search site, which easily guides you through the already catalogued content using keywords. To understand more about what to expect in terms of future access, you can visit the website that lists recent acquisitions and donations and notable works and collections. Another important research resource at the GRI is the Getty Library, one of the world’s most comprehensive libraries focused on the history of art, architecture, and archaeology. It includes over 1.5 million volumes of books, periodicals, and sales catalogs. For those of us interested in the preservation of cultural heritage, the invaluable Conservation Collection comprises approximately 64,000 titles and nearly 400 current serial subscriptions. The library catalogue allows for combined search of published secondary sources and special collections.

For those researching the multifaceted phenomena of Fluxus, it is advisable to conduct searches across diverse collections using different available tools, as crucial information may be hidden in unexpected places. For example, valuable insights can often be found within the correspondence housed in the archives of individuals who are not directly linked to Fluxus. Furthermore, the archives of artistic venues could prove significant. Take, for instance, New York City’s alternative art space The Kitchen, which hosted numerous Fluxus events, including A Flux Concert Party in 1979.

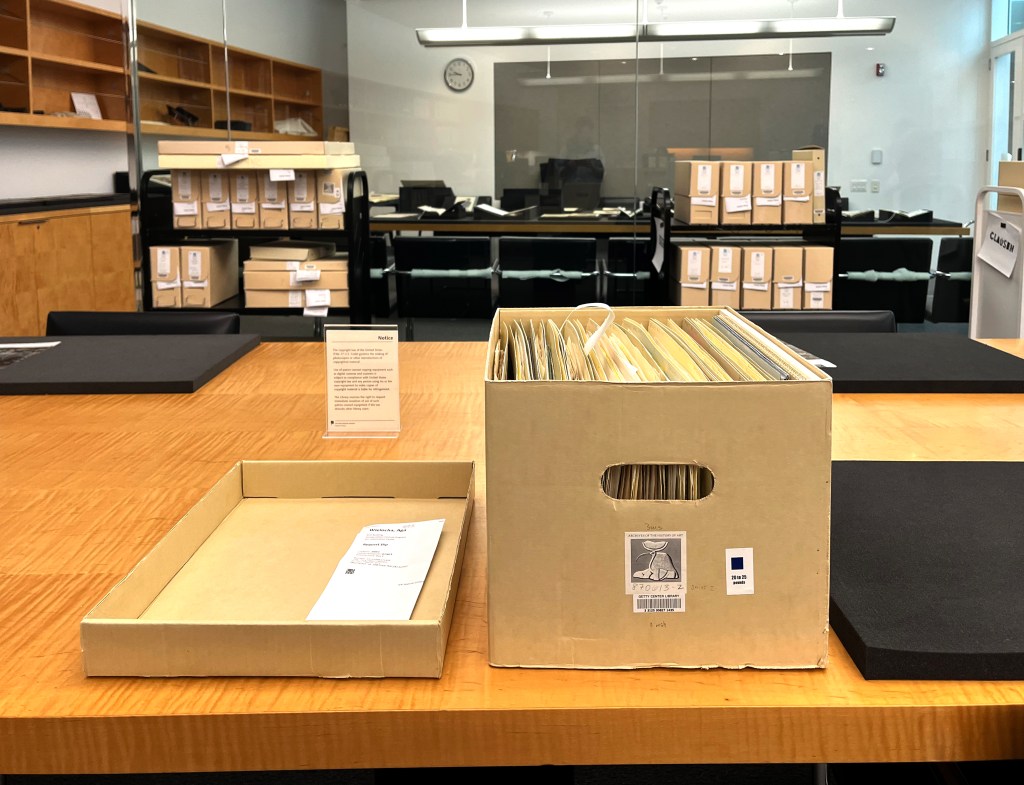

A few notes on accessing the collection: Your requested materials will be delivered to the reading room on a cart labeled with your name. While you’re limited to consulting one box and one item at a time, these are the primary restrictions. Beyond this, you’re free to interact with the requested objects at your own pace. The attentive staff of the Special Collections are always on hand to assist you. They can answer questions, offer advice on handling delicate materials (such as when to use gloves), and provide any other guidance you might need. You may take photographs of the materials for your personal reference, though separate permission is required for publishing these images.

It is good to know however, that the instruction for interacting with objects might often come in the form of notes tucked inside the archival boxes—messages left by collection keepers, typically the GRI conservation team, for future researchers. During our exploration of the objects Jean Brown’s Papers in the Special Collections reading room, we examined Ay-O’s Finger Box (1964). The piece features a wooden box with sixteen holes offering a unique tactile experience, housed in a beautifully crafted archival container accompanied by two documents. The first is a photocopy of George Maciunas’s letter to Jean Brown, detailing the work’s use and maintenance in handwriting familiar to all Fluxus researchers. Some descriptions of the containers accessible through the holes are straightforward—”Vaseline”, “sawdust”, “balls”, “paper”—while others are more cryptic, like “elbow” and “solid”. One container requires water, filled three-quarters full and carefully screwed back in place. An internal alarm, activated through one hole, needs battery changes. For the Vaseline-filled hole, Maciunas suggests toothpaste as an alternative. Further, he instructs that “when people insert finger in vaseline [sic] they should have a finger wiped off before inserting finger in another hole, otherwise it will mess up other holes.” The Finger Box as an archival object is not functioning as intended – the containers are not replenished with water, Vaseline, or toothpaste, and the alarm was deprived of batteries to avoid potential leakage. The second document, a contemporary one, starkly confirms this non-functional status by urging researchers to “resist the temptation: don’t stick your finger in holes! The brittle rubber membranes will rip or even fall apart” and quashing all hope of interaction.

As you prepare to immerse yourself in the archives, remember to leave your water bottle on a designated cart outside the reading room and bring a light jacket, as the space can get quite cool. More importantly, come with an open mind and allow yourself ample time—many objects demand close examination, imaginative thinking and additional research to comprehend how they might have functioned and been used in the past.

When you need a break from your research, the Getty’s gardens offer a retreat with breathtaking ocean views. Enjoy!

- See: https://www.getty.edu/research/collections/help#identifying-digital-material ↩︎

- See e.g.: “Prière de Toucher: Challenges of Conservation and Access” in Reed, Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant-Garde Archive, 106. ↩︎

Featured photo: In the GRI Special Collection reading room.

Photo: Cassia Davis. © 2024 J. Paul Getty Trust.