Authored by a scholar and practice-based researcher Inbal Strauss, the paper “Capri Battery: Powering Decolonial Display Practices through Multisensory Interaction” was presented at the 112th College Art Conference in Chicago within the session Activating Fluxus, Expanding Conservation, organized by our research team on February 15, 2024. Below we have made the presentation available to everyone who was unable to attend the conference.

Introduction

According to the dominant Western paradigm of aesthetic reception, what distinguishes artworks from everyday objects is that they provide aesthetic experiences exclusively through visual perception. Correspondingly, Fluxus objects are customarily exhibited on plinths and inside vitrines despite the fact they often consist of appropriated everyday objects and were made for so-called “viewers” to interact with in multisensory ways. How, then, might everyday objects, which are designed for users to interact with in visual as well as tactile, proprioceptive, auditory, olfactory, and gustatory ways, help Fluxus objects challenge the privilege of the ocular in aesthetic reception and inform contemporary display practices?

While art’s prohibition on physical interaction is commonly considered a conservation measure, it is also criticized for being rooted in colonialist and racial hierarchies of the senses that privilege sight over marginalized sensory modalities historically considered non-Western (Edwards, Gosden & Phillips 2006: 7-22). The Western association of sight—and to a lesser degree hearing—with reason and rationality, and touch, taste and smell with bodily pleasures and irrationality, have disembodied aesthetic experiences and shape conservation and display practices to this day (Edwards, Gosden & Phillips 2006: 7-22).

Kemp: The Methodology of Reception Aesthetics

In accordance with the dominant Western paradigm of aesthetic reception, traditional reception theories focus on vision. In his essay, “The Work of Art and its Beholder: The Methodology of the Aesthetics of Reception,” the art historian Wolfgang Kemp identifies the forms of address with which artworks form an offer of reception capable of “activating the beholder to take part in the[ir] construction” (Kemp 1998: 186). These include such things as composition, perspective, and depicted figures or elements that orient the viewer, direct their gaze, and provide clues on how to read the work. Yet, the overarching form of address is the aesthetics of indeterminacy, or the “blanks” of aesthetic representation, which the work deploys to “trigger acts of ideation” and consequently be “finished by the beholder” (Kemp 1998: 188). Through forms of address, the work invites the viewer to receive it in a suggested way—to perform a certain role that will complete it. Significantly, the viewer “brings more than [their] open eyes to the perception/reception of the work”; they also bring what Kemp calls their inner preconditions (Kemp 1998: 180).

Moreover, alongside inner preconditions, Kemp describes the extrinsic conditions of access/appearance. He notes that artworks are accessible to the viewer “under conditions that are mostly safeguarded by institutions and that, in themselves, require certain patterns of behavior on the part of the recipient. Extrinsic conditions of access comprise, for example, the architectural surround and the corresponding ritual behaviour expected by . . . the bourgeois institutions of art” (Kemp 1998: 185). In our case, consider the modern gallery or so-called “white cube” space, wherein objects are displayed on plinths, inside vitrines, or behind ropes. Such means of display, to which Kemp refers as context markers, imply the corresponding behaviour of exclusively visual perception (Kemp 1998: 185).

Norman: The Design of Everyday Objects

In his seminal book The Design of Everyday Things, the usability engineer Donald Norman identifies the principles of interaction with which designers form the discoverability of the everyday object, which communicates to the user “what it does, how it works, and what operations are possible” (Norman 2013: 10).

(1) Affordances are the relationship between an object’s properties and the agent’s capabilities. So handsaws afford sawing if users have a basic understanding of the physics of cutting and an able hand. In other words, provided users have the relevant inner and—as it were—“outer” preconditions.

(2) Constraints prescribe the users’ role by restricting possible actions. Physical constraints restrict “such things as the order in which parts can go together and the ways by which an object can be moved, picked up, or otherwise manipulated” (Norman 2013: 76). For example, a three-pronged plug will only fit into a three-hole socket. Yet, cultural constraints, akin to social norms, are “learned artificial restrictions on behaviour” that govern our interactions (Norman 2013: 76). To illustrate the distinction, consider the modern exhibition space, which may contain a host of physical constraints, such as glass vitrines preventing us from physically interacting with the exhibits. Yet, the cultural constraint on physically interacting with exhibits is usually enough to enforce the “correct” behaviour even in the absence of physical constraints. Indeed, these physical and cultural constraints comprise what Kemp calls “extrinsic conditions of access/appearance.”

(3) Feedback communicates the results of our actions. Positive feedback confirms we are acting correctly, whereas negative feedback (or the lack of positive feedback) indicates we should adjust our actions to yield the intended result or, alternatively, that there is a fault with the system. For example, elevator buttons may light up when pressed to confirm our request has been registered. If they do not, we get no positive feedback, which may serve as negative feedback.

Feedback may also be auditory, olfactory, gustatory, or haptic: sounds, odors, or vibrations. And it may also be natural rather than artificial, like the elevator’s upward or downward movement. Smooth and quiet operations provide positive feedback, whereas strident sounds, burnt odors, or turbulent motions indicate that we should adjust our actions or fix the system.

(4) Mapping refers to the correspondence between two sets of things and is, therefore, a key principle in designing controls and displays. Some mappings use color (yellow files go in the yellow cabinet), some correspond to universal conventions (turning dials clockwise leads to an increase and anti-clockwise leads to a decrease), and others follow “spatial analogies” (which is why the buttons in the elevator are arranged in ascending numerical order).

(5) Lastly, the mental model is “an explanation, usually highly simplified, of how something works” (Norman 2013: 25). For example, the computer “desktop” displays graphic representations of files within folders, which explain how to interact with computers. Mental models may be provided through manuals or similar designs we have previously interacted with, yet according to Norman, they should ideally be inferable from the design itself, and the best way for users to acquire a mental model is from the perceived structure of the design—its affordances, constraints, and mappings.

Capri Battery: An Analysis from the Twin Optics of Kemp and Norman

If so, designers employ principles of interaction that appeal to users’ preconditions to form discoverability that guides users in executing the functions of everyday objects. Comparably, artists employ forms of address that appeal to viewers’ preconditions to form an offer of reception that guides viewers in completing the meanings of artworks. Therefore, perhaps applying Norman’s principles to the analysis of artworks can reveal how they solicit intellectual agency through multisensory perception. Approximating viewer with user, and accordingly, artist with designer, might reveal how artists prescribe an intellectual role through physical interaction.

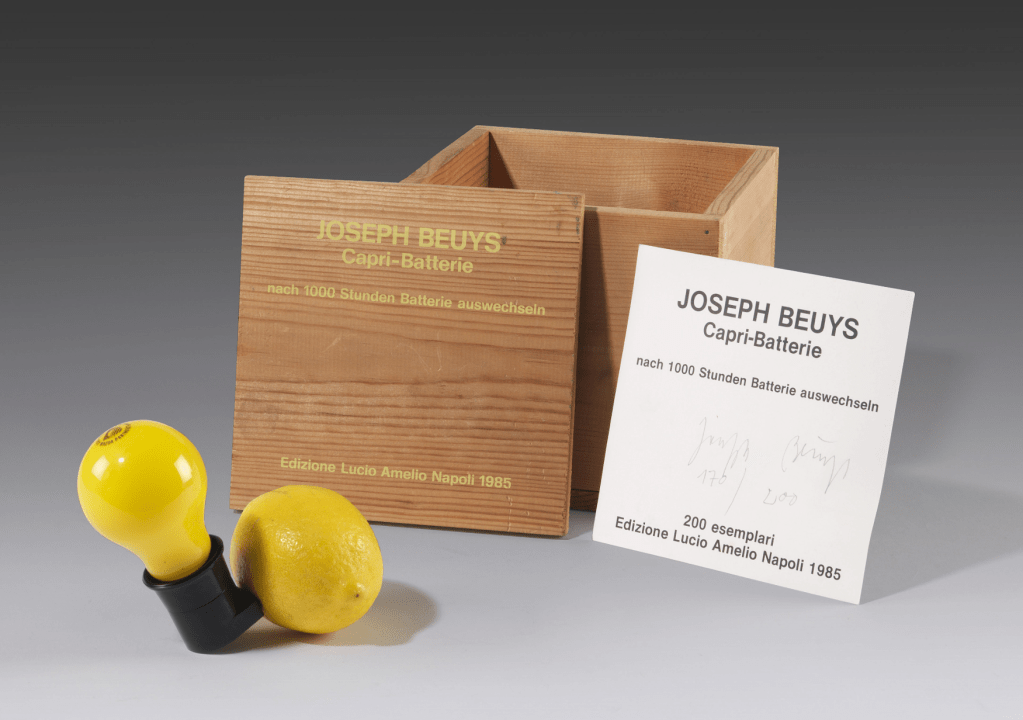

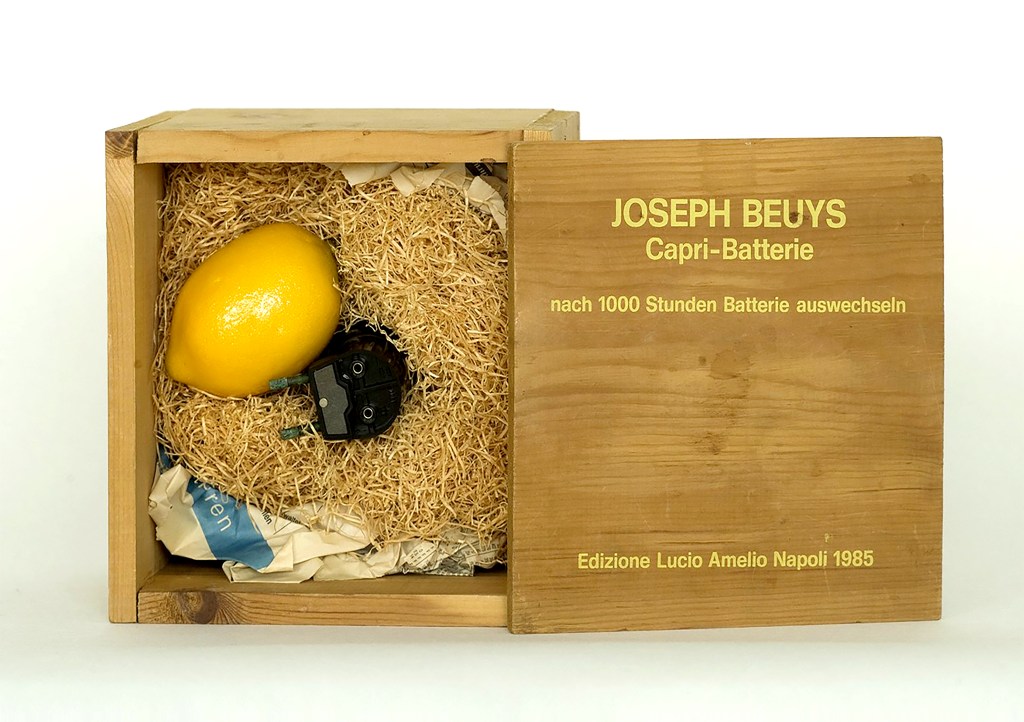

I will focus on Capri Battery, created in 1985 by Joseph Beuys, a German avant-gardist known for his involvement with 1960s Fluxus. Although not officially “Fluxus,” the work represents similar concerns raised by Fluxus works in institutions and on display. Beuys gifted friends and acquaintances 200 copies of the work, which consists of a yellow lightbulb, a black socket adapter, and a lemon encased in a wooden box, and accompanied by the tongue-in-cheek inscription “change battery every 1,000 hours.” While Beuys chose to display one copy (with no box or inscription) in a vitrine, in gifting most copies boxed and unplugged, Beuys turns the ordinarily “passive” beholders into active agents.

Nevertheless, institutions commonly display the work on a plinth, inside a vitrine, and often with a plastic rather than a real lemon. From a practical perspective, these institutional display decisions prevent damage and save institutions from continually replenishing the decaying exhibit with fresh lemons. However, from a critical perspective, the “conservationist” display decisions are questionable because multiple copies exist, because the work is easily replicable using off-the-shelf items, and because Beuys designed it for physical interaction and arguably appropriated the lemon for its ephemeral and multisensorial properties.

At first sight, there’s something amusing about the work. Yet, surely amusement isn’t the ultimate response Beuys aimed to elicit. Presumably, the twin yellow “bulbs” are a colour-coded message or, rather, a form of mapping—of supporting the mental model. As the title and inscription (a type of “manual”) suggest, the work is to act as or represent a battery. In including a standard lightbulb and socket adapter but swapping the socket for a lemon, Beuys’s mapping supports the mental model of a lemon battery, which we can all vaguely recall from the primary school science experiment.

Nevertheless, while the recipient may have the inner precondition of familiarity with the model of a lemon battery, and even though the reception took place outside the traditional site of reception, the cultural constraint on physical interaction with art is so deep-seated that recipients may have still been apprehensive about breaching the cultural constraint, and, of course, breaching the physical constraint on plugging a two-pronged plug into a lemon rather than a corresponding socket. Yet, again, the mapping between the colour, shape, and size of the lemon and lightbulb is Beuys’s way of “winking” at recipients to eliminate any apprehension.

That said, Capri Battery is not actually engineered to function as a lemon battery. Consequently, we can imagine recipients feeling bemused rather than further amused when they follow Beuys’s prescription only to encounter a lack of positive feedback when the lightbulb emits no light, and natural negative feedback from the stinging sensation and sour smell (and possibly taste) of the lemon juice dripping down their hands. Yet, perhaps instead of considering this feedback as indicating incorrect action, we should consider Beuys deliberately designed a dysfunctional lemon battery to afford a cognitive dissonance that triggers acts of ideation. By forming a false offer of reception, Beuys prescribed interacting agents an ultimately intellectual role in completing the work. Since negative feedback and the lack of positive feedback indicate we should adjust our actions to yield the intended result, perhaps Capri Battery was not designed to prescribe an action that completes it as such, but rather, to be a “call for action”—calling to change our actions and fix the broken energy system. It could be said that the proverbial lightbulb lighting up above recipients’ heads when they realised this is what filled in the “blank.”

Indeed, according to the work’s accepted reading, informed by the fact Beuys was an environmentalist and a founding member of the German Green Party, it calls for a reconsideration of fossil fuels as an energy source. Designed on the Mediterranean island of Capri, where strong sunlight provides favourable conditions for the cultivation of lemons, the choice of the two round bright yellow “bulbs” can be understood as another layer of mapping that validates this environmental reading by alluding specifically to solar power as an alternative, more sustainable source of energy. It does this by supporting the mental model of the sun as a renewable energy source: the lemon represents the sun’s energy in its stored form, the lightbulb represents the sun’s energy as a light source, and together, they represent the circularity of the sun’s physical mechanism of operation.

On this account, the choice of a lemon and a yellow incandescent lightbulb creates multi-layered mapping that both prescribes physical interaction by supporting the mental model of a lemon battery and triggers a specific, environmental act of ideation by supporting the corollary mental model of the sun as a battery. If we consider artworks to be instrumental (at least insofar they can be used as a vehicle for social change), then we could say that agents driven to action by Capri Battery take part not only in its completion but also in the literal execution of its function.

If so, through the various design decisions embodied in the work, Buys prescribed physical interaction. Yet, this physical interaction ultimately led recipients to perform an intellectual role that completed the work. By prescribing an intellectual role through multisensory perception, the workdemonstrates that intellectual agency need not be solicited exclusively through visual perception, and that its customary institutional display undermines the potential social, political, and environmental impact of its intended reception.

Conclusion

To conclude, I hope this case study demonstrates how thinking of interactive artworks—particularly those representing Fluxus concerns—as “designed” objects can inform contemporary display practices that will help re-embody aesthetic experiences and decolonize the anachronistic yet still-pervasive visualist paradigm of aesthetic reception/perception.

References

Edwards, E., Gosden, C., & Phillips, R. (2006). Introduction. In E. Edwards, C. Gosden, & R. Phillips (Eds.), Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture (1–31). Berg.

Kemp, W. (1998 [1986]). The Work of Art and Its Beholder: The Methodology of the Aesthetic of Reception. In M. Cheetham, M. Holly, & K. Moxey (Eds.), The Subjects of Art History: Historical Objects in Contemporary Perspective (180–196). Cambridge University Press.

Norman, D. (2013 [1988]). The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition. MIT Press.

About the author

Inbal Strauss is an artist and art theorist investigating the politics of cultural labour. Her recently completed doctorate from the University of Oxford explored the potential and implications of considering art-making as a design process, and correspondingly, artworks as “designed objects.” She was a 2020 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the Ashmolean Museum and a 2019 AHRC Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. She taught at Oxford, Stanford, Sarah Lawrence, and more. Her artworks and writings have appeared in numerous exhibitions and publications, including in the upcoming issue of the Sorbonne’s peer-reviewed journal Sillages critiques.

To cite this script

Inbal Strauss, “Capri Battery: Powering Decolonial Display Practices through Multisensory Interaction”. Presentation at the 112th College Art Association Conference, Chicago, within Activating Fluxus, Expanding Conservation session (February 15, 2024). https://activatingfluxus.com/2024/03/05/capri-battery-powering-decolonial-display-practices-through-multisensory-interaction-by-inbal-strauss/